The Abhidhamma is a body of literature that emerged shortly after the lifetime of the Buddha, comprising the third of the “three baskets” (Tipitaka) of the early Buddhist canon. The word also refers broadly to a body of thought whose roots are in the psychological teachings and meditation practices of the suttas (the discourses) and whose branches reach far into the mature philosophical discussions of the Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions.

The Abhidhamma is essentially an attempt to systematize the Buddha’s teachings about the dynamics of moment-to-moment experience as it unfolds in the stream of consciousness. The following pages offer a brief outline of some of the main components of the system. More detail of the Pali version presented here can be found in Bhikkhu Bodhi’s excellent Comprehensive Manual of Abhidhamma (BPS/Pariyatti).

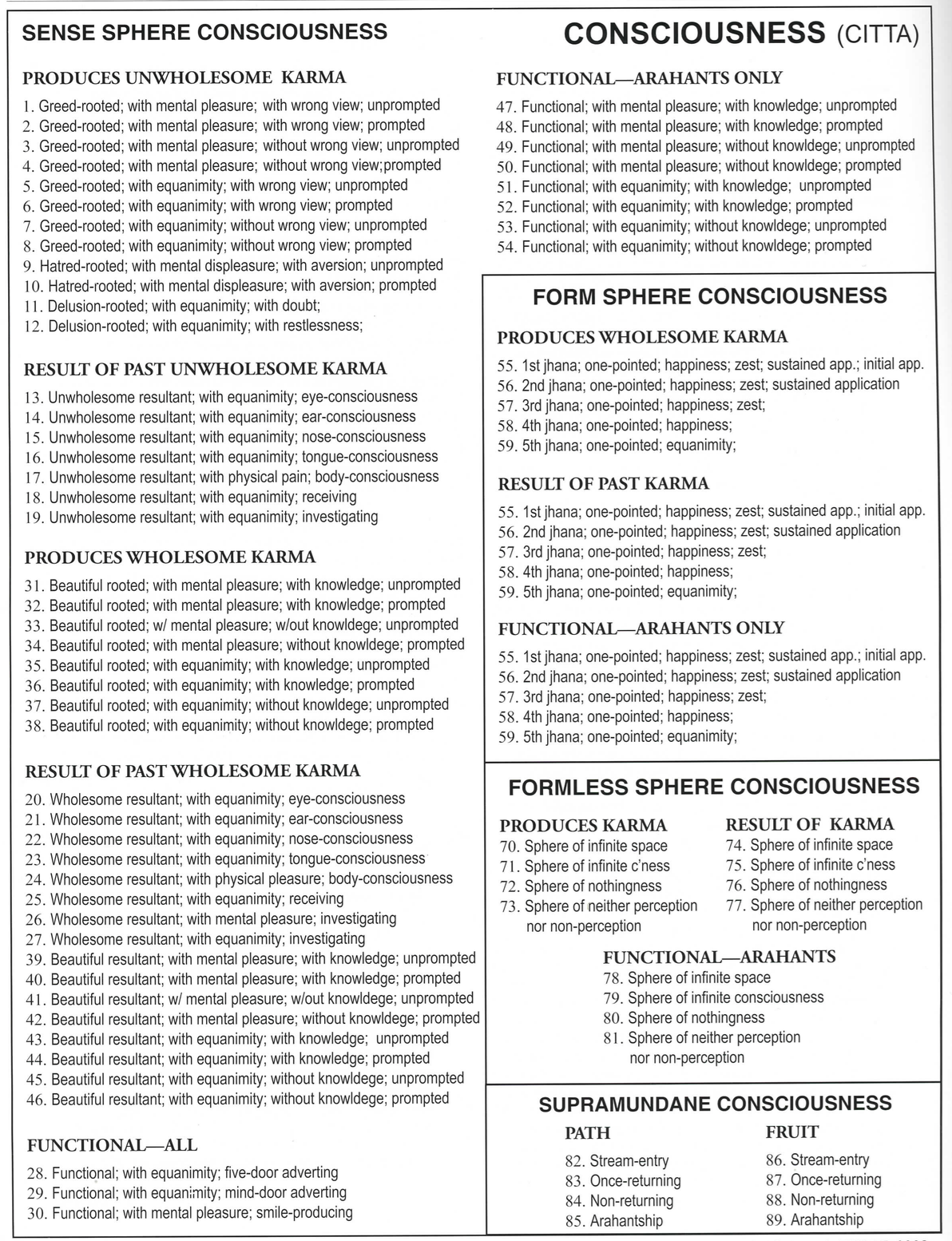

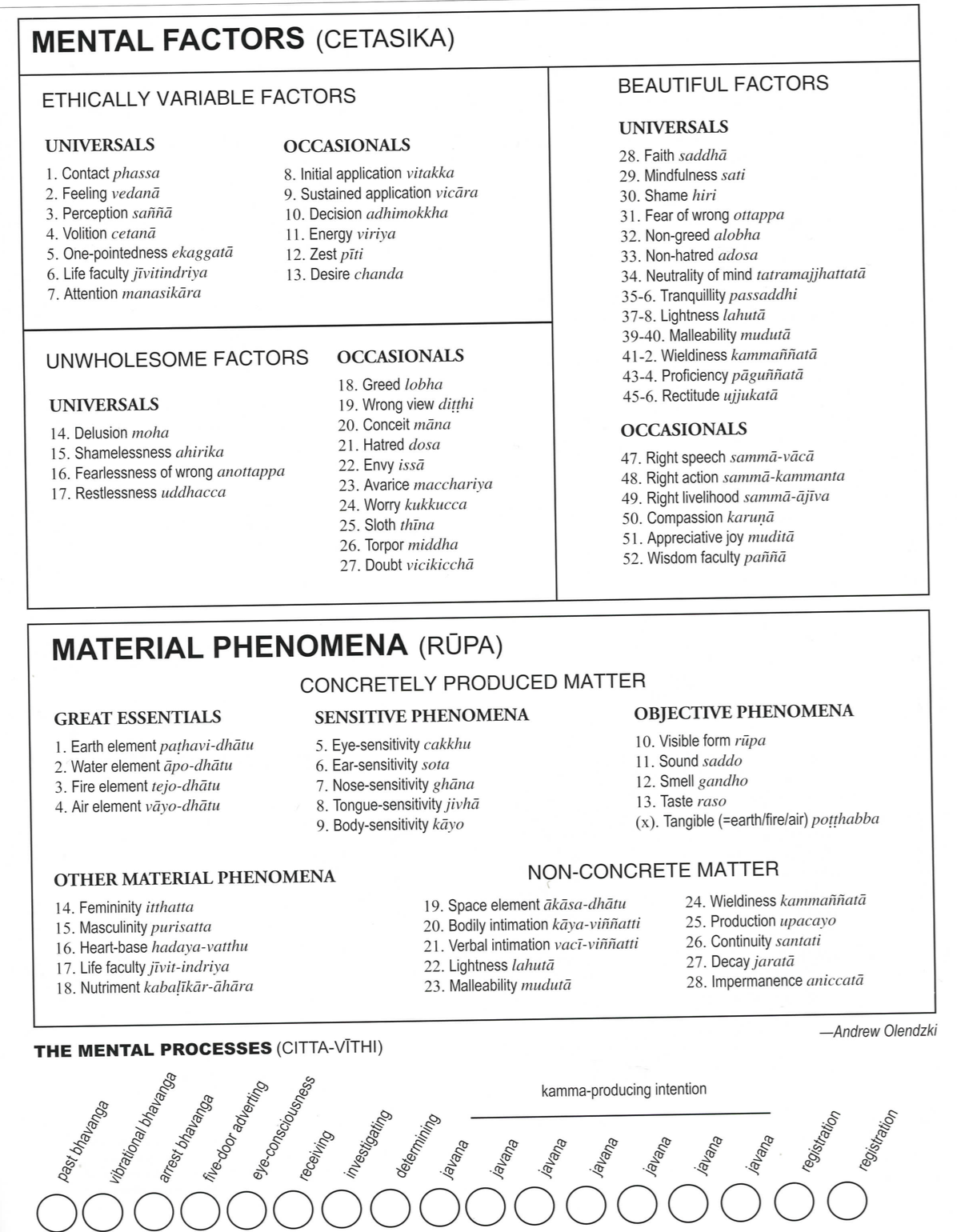

In summary, the Abhidhamma describes how 28 physical phenomena co-arise with 52 mental factors, manifesting as 89 types of consciousness, which unfold in series of 17 mind moments, governed by 24 types of causal relation. One of its methods is to take a single thought-moment of experience, accessible by means of (rather advanced capabilities of) insight meditation, and then identify the characteristics of that moment of consciousness. Numerous things might be discerned about it:

1) Consciousness (citta). Each mind moment will manifest as one of the 89 forms of consciousness enumerated on this list. It will be consciousness taking place on a certain sphere or level of existence, from the mundane sense-oriented sphere, through the higher form and formless spheres accessible by the purification practices of absorption (jhāna), all the way to the non-ordinary states of consciousness associated with the attainment of awakening. In addition, this moment of consciousness will be known to be either wholesome, unwholesome or neutral in terms of its karmic effect on subsequent moments. Finally, each moment will be classified either as a karma-producing mind moment, the result of previous karma-producing moments, or as a purely functional moment that is neither. The moment of consciousness under review will be seen to be only one of the 89 possibilities; the next moment is sure to be different.

2) Mental factors (cetasika). There are a total of 52 subfunctions of the mind, called mental factors, which cooperate in various configurations to assist consciousness in the knowing of an object. Among these, 7 arise in all mind moments and are called universals, while 6 others may or may not be present and are thus called occasionals. These 13 mental factors are ethically variable because they can arise in either wholesome or unwholesome states of mind. The next 14 factors are always unwholesome, and their presence renders all moments of consciousness containing them unwholesome. These too can arise in various internal combinations, but the first 4 of them are always present in every unwholesome mind moment. The final 25 mental factors are always wholesome (called beautiful), and any mind moment containing them will become wholesome by their presence. These too can arise in various combinations involving universal and occasional wholesome factors. An important principle of the system is that wholesome and unwholesome factors can never arise together in the same mind moment.

3) Material form (rūpa). All the 28 material phenomena are based on the 4 great elements, earth, water, air, and fire (i.e., solid, liquid, gas, plasma), and these four also all arise together in different combinations or saturations. Material phenomena include both the organs and the objects of experience, as well as a number of supporting life functions. A category of non-concrete matter includes various characteristics of material phenomena not construed as things in their own right. With material factors, as with mental factors, there are various rules governing the way they can arise in combination.

4) The mental process (citta-vīthi). The Abhidhamma, influenced primarily by later tradition, identifies 17 different functions of mind that unfold one after another over time in the stream of consciousness. From a baseline of unconscious mental activity, the mind responds to a stimulus presenting at a sense door by gradually taking notice and turning attention toward the object, cognizing the object in a moment of seeing, hearing, etc., and then taking a few moments to receive, investigate and determine what is happening. There are then 7 moments of intentional response in which wholesome or unwholesome karma is produced, followed in some cases by a couple of moments of recognition. If the mental process is taking place at the mind door, rather than at a sense door, it is somewhat quicker and cuts out a few steps. After this series, the mind lapses again into an unconscious state until the next stimulation. The details of this process are described (in the later texts) not only for normal mental processes, but also for jhāna states, the process of rebirth and liberation.

5) Causal relations (paccaya). Not shown on these pages is the list of 24 causal relations governing the relationship between all possible combinations of material phenomena, mental factors, and consciousness. Factors within a single group (e.g., mental, material), within a single mind moment, between different mind moments, between individual and group factors—all these are spelled out exhaustively (and yes, exhaustingly) in the culminating text of the Abhidhamma section of the canon, the Patthana.

This may all seem rather busy to those of us familiar with a more simple and open approach to meditation, but this science of the mind offers a rigorous description of the landscape revealed by insight meditation, taken to its furthest stages of development. The Buddha seems to best express the crux of the Abhidhamma—the relationship between insight, knowledge, impermanence, dependent origination, awakening, and liberation—when he said of his chief disciple (and probable guiding architect of the Abhidhamma):

“Sāriputta has deep…penetrative wisdom. For half a month Sāriputta had insight into states one by one as they occurred:…known to him those states arose, known they were present, known they disappeared. He understood thus: ‘So indeed, these states, not having been, come into being; having been, they vanish.’ Regarding those states, he abided unattracted, unrepelled, independent, unattached, free, unfettered, with a mind rid of barriers.” Anupada Sutta (M 111)