Shantideva is one of the most revered teachers of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. His most important text, the Bodhicāryāvatāra, was composed in Sanskrit in the eighth century and translated into Tibetan in the eleventh century. There are numerous translations and commentaries to this text, most of them drawn from the Tibetan tradition, and the text we will be using today is from the Tibetan.

Like many Buddhist teachers, we do not know a lot definitively about Shantideva, whose name means Lord (deva) of Peace (śānti). There are different versions of his life, with one source, for example, saying he is an oldest son, and another calling him the youngest son. It may even be that there were more than one person by the same name, or that texts written by others were attributed to him. At any rate his dates are generally accepted to be 685-763 C.E.

Shantideva was a very idiosyncratic Indian monk living and teaching at Nālanda, the great Buddhist institution located not far from Vulture’s Peak in Bihar. Its ruins can still be observed today. It was destroyed by one of the Muslim invasions of India, but there are still monks’ bowls partially filled with rice that you can see there among the ruins. Nālanda was the premier Buddhist university of its time, and Shantideva was one of its more colorful inhabitants. In some versions of the story he is not called Shantideva, but Bhusuku. It sounds almost Japanese, but perhaps it is meant to be humorous. It means he was kind of a lazy monk: He did nothing except bhu, su, and ku, which means to eat, to walk around, and to shit. Bhusuku, “lazy monk”—that was all he was good for.

The monks at Nālanda were all real scholars, and they tended to look down on Bhusuku. He didn’t take part in the ceremonies. He didn’t take meals or join communal prayers. He always showed up late to things. There was a tradition at Nālanda that each of the monks was to contribute to the community by reciting scripture. And Shantideva missed his turn every time. He could never quite make it. So the monks devised a plan to show him up, to give him his comeuppance. Can you imagine this community of monks thinking, “Let’s get this little…” So this is the legend:

They arranged for a time when they would get him there and they would announce as a surprise that it was his turn. They had built a throne where the teacher sat, and they had made it so high that he would fall and embarrass himself in front of the community just trying to get up to it. They were really kind of spiteful; they didn’t like anybody not pulling their weight, and he was definitely a slacker.

So here’s Shantideva, they get him there on some ruse, and then say, okay, it’s your turn, go sit on the throne. And to their amazement, he had no problem at all getting up there. He turned to them and said, “Now, would you like me to recite an ancient scripture, or would you like to hear something new?” So they said, “Lay something new on us.” And he started to recite none other than the text we’re going to read together, the Bodhicāryāvatāra, completely new, completely beautiful, and in flowing Sanskrit verse.

“Even the fleas and the gnats, even the grubs, who hear this text being recited, will one day attain enlightenment.”

Old Bhusuku did it! He did it! This is not just my opinion. This man Shantideva found a way to say it in verse, how a thought of bodhicitta—the heartfelt aspiration that one will commit to the goal of awakening all sentient beings—comes to arise, how it can be maintained, and how it can be increased. The way of the Bodhisattva. The full title of this text means entering or going down into (avatāra) the way, the behavior or the activities (cāriya) of a Bodhisattva, one whose whole being is set on enlightenment for all beings.

This text is slightly under 1,000 four-line verses, and the structure of it was unique in its time. It is divided into ten chapters, and Shantideva has written it—in this case recited it—such that every three chapters forms a unit, with the tenth being a dedication of merit for having created the text. It deals with everything from the beginning of the thought of enlightenment, up to Buddhahood itself.

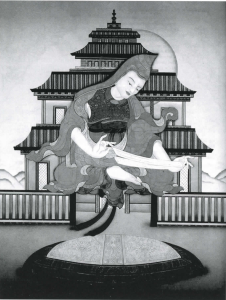

The ninth chapter is the famous wisdom chapter, which stands as a text in its own right. And the story is told that when he came to the ninth chapter, and he was reciting, he suddenly started to levitate, his body just rose from his seat. I found one depiction of this. Here we see Shantideva, with the famed Nālanda University in the background. His cushion throne is there, and he’s not sitting on it; there is air between his body and the cushion. He floats right on out of sight as he’s reciting the ninth chapter on wisdom, Voidness of Self. And he completely disappears, never to be seen again. They don’t see him anymore, but they hear his voice. And they recognize that what he is saying is something totally new.

One of the verses from Shantideva’s text says, “Even the fleas and the gnats, even the grubs, who hear this text being recited, will one day attain enlightenment.” I’m absolutely convinced it’s true. Even the grubs will attain enlightenment. So it’s often a practice in Tibetan monastic institutions that the Bodhicāryāvatāra will be taken outside and read aloud so that everything in the natural environment, the insects, the birds, would hear it, and from hearing it, they would form an aspiration, that all beings, without exception, would one day attain complete and perfect enlightenment. So reading the text is a practice. Reading it aloud is an additional kind of practice. Reading it in the hearing of others, that too is a practice. So here in the Dharma Hall today, we will practice first by reading this text, in our own voices, to the other folk in this room.

There are five translations of the text in English that I know of, and four very fine commentaries. This one we’ll read from this weekend is the only one translated to be read aloud in iambic pentameter. I think it’s really the best translation out there. It’s the only translation that bears in mind one of the reasons this text has been so powerful throughout history, and that is because it is so beautiful in verse. They did it! These people did it so that it’s pleasing to people. That’s another reason to read it aloud, because it’s pleasing not only to the gnats or the grubs, but to us as well.

*

Why is this such a special text? Tibetans have treasured it for several reasons. In the wisdom chapter Shantideva has captured in verse the profound point of view of the Madhyamaka. This is the premier wisdom school of Nāgārjuna which articulates the wisdom that liberates us from saṃsāra. He thus captures in verse the core teaching of the Mahāyāna in the context of telling us the path to Buddhahood.

From the time of the Buddha, almost 2,600 years ago, in India, sixth century BCE, a person named Siddhartha Gautama expounds this teaching. The fundamentals of that teaching—which British explorers, who like to put “isms” on things, called Buddhism—is referred to as Dharma. Dharma is what holds us back from harm. Dharma—from the Sanskrit verb root “dhr,” to hold—holds us back from harm and holds us together. The Buddha expounded the Dharma, which can be summed in terms of the Four Noble Truths: There is suffering, there is the cause of suffering, there is the cessation of suffering, and there is a path that leads to the cessation of suffering. Under the rubric of “path,” it is said that the Buddha taught 84,000 different methods. We should be able to commit to one of them! When we see Japanese Zen, when we see Theravadan Vipassanā or Insight, when we see Tibetan Tantra—these are simply different methods of practice.

Shantideva’s text is about the heart of Mahāyāna practice, which is bodhicitta, the thought of enlightenment that begins with including others. I sit on the cushion, presumably, because I have some concern for myself. And we can wed that concern with the concern for all others. That liberation should be something that is open to all of us, and we should start our practice from there—that is Mahāyāna. And that is what this text is about.

The text explains first, in its first three chapters, that bodhicitta—that precious bodhicitta, so rare in this world—is a totally virtuous thought. How is it that something so precious and rare as the virtuous thought, bodhicitta, arises in the world? “May all other beings be free from suffering; then I’ll think about myself”—that is a rare thought. How does that happen at all? Then in the next three chapters the theme shifts to maintaining what has arisen. “May bodhicitta, precious and sublime, arise where it has not yet come to be. And where it has arisen, may it never fail, but grow and flourish ever more and more.” The final three chapters address how it may be increased and spread through the worlds.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama was recently asked by a reporter—and this is rare given the circumstances of Tibet right now, there being a very real crackdown —”Do you really think, your Holiness, that good is possible in this crazy world, and that it has any chance of overcoming the chaos, the evil and all the negativity in the world today?” And His Holiness, without a moment’s delay, said “But of course it does. Sure.” Now I find that amazing. But, on some level, I understand it.

I do battle all the time with the thought, “How in the world can compassion compare with the negative stuff that is out there?” But this just shows up my own limitations. Because in the same way that even those grubs will get enlightened one a day, I hope there will come a time when the positive will outlive the negative. That’s His Holiness’ opinion, and I’m coming more and more to agree with it. The positive, almost magical, idea that it is possible to think we will all become, each one of us, enlightened beings. That is a powerful thought. That is the bodhicitta.

For a long time I dealt with really low self-esteem; I’ve still got traces of it. I grew up in the Jim Crow South—white drinking fountains, colored drinking fountains, that whole thing. People were saying, “What’s the matter with you? You’ve got a place. You’re trying to get out of it. Don’t you know your place?” It cuts deep on a kid’s psyche, especially a sensitive, moody, delicate kid. But I think there are methods capable of helping us actualize outlooks and actions that are virtuous, in any situation. Little by little, step by step, we train ourselves. I found these methods of transformation in the Tibetan tradition, and there are others in other Buddhist traditions. I’m still Baptist, though—a Tibetan Baptist Buddhist.

Tibetans have been using these methods since Buddhism was introduced there, so for centuries upon centuries, they have been practicing this. The hallmark of Tibetan Buddhist practice is this: that one can transform one’s ordinary body, speech and mind into the body, speech and mind of a Buddha, an enlightened being. And I think when you meet certain Lamas who model or manifest this, you believe in this possibility.

It’s real. The Tantra says, even in these degenerate times, it is possible to transform one’s ordinary body, speech and mind into the body, speech and mind of an enlightened one. That’s possible for each and every one of us, even if we can’t see the end now.

We might as well begin now on this Bodhicitta Bodhisattva Mahāyāna path. Because eventually, even if it takes lifetimes, one day we are going to do it. I don’t know about this lifetime reincarnation thing, but we can see the incremental changes, step by step, even in this lifetime. So imagine the day, maybe countless lifetimes in the future, when we do it. If we’re changing negative habitual thinking to positive habitual thinking, the negative will run its course and the positive will eventually outweigh the negative.

The Dhammapada says, “Hatred is never appeased by hatred. Hatred is only appeased by love. This is an eternal law.” The term for eternal law there is Dhamma. If you want to know the Dharma in a nutshell, it is here in this verse. And this book, Shantideva’s Bodhicāryāvatāra, is about love and compassion.

Each of our sessions in the Dharma Hall will end with one of Shantideva’s  dedication verses. I think it sends us on the way from our Dharma Hall well. I really hope we get a chance to read all of these, even if we don’t explicate all of them. Let’s try reading this one together now. See if you can connect with this and make it heartfelt.

dedication verses. I think it sends us on the way from our Dharma Hall well. I really hope we get a chance to read all of these, even if we don’t explicate all of them. Let’s try reading this one together now. See if you can connect with this and make it heartfelt.

May beings everywhere who suffer

Torment in their minds and bodies

Have, by virtue of my merit,

Joy and happiness in boundless measure.

(Chapter 10, verse 2)

One can transform one’s ordinary body, speech and mind into the body, speech and mind of a Buddha.

Let us try to form that wish. Let’s try to reflect on that a while: “May all beings have happiness and the cause of happiness.” Let us think, as we will, in a mettā way, with loving kindness, by thinking these lines:

May all beings be free from danger,

may all beings have bodily happiness,

may all beings have mental happiness,

may all beings know the ease of well being,

may all beings be free from danger.

Like a blind person who finds a jewel in his house, let us take up bodhicitta, embrace it, and make it our own. Let’s begin here.

This article is extracted from a program offered at BCBS in March 2008 by Prof. Jan Willis, professor of Religion at Wesleyan University and one of the earliest American scholar-practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism.