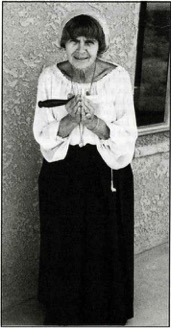

Ruth Denison is the founder and resident teacher of Dhamma Dena Desert Vipassana Center in Joshua Tree, California. She is the first generation of women teachers of vipassanā in the West, and has been teaching at Insight Meditation Society in Barre since its inception in 1976. Ruth shared her life story and thoughts with Insight’s editors while teaching at IMS in the fall of 1996.

Ruth, you have a fascinating and unusual life story to tell. Can you share some of it with us? How did you get involved in things spiritual?

I was born in a small village in eastern Germany, near the present Polish border, in what used to be called East Prussia. As a child I had experiences of saints and angels talking to me. Since I was raised in a Christian tradition, it is not unusual to interpret them in this light. I took refuge in them without knowing what I was doing. Later, as a teenager, I read about Theresa of Avila and was quite affected by the narration of her experiences.

Prior to the war I was an elementary school teacher. Then, when the war ended, the Russians pushed westward and everyone had to evacuate. There were lines of horse-drawn wagons many miles long, and many people froze to death in sub-zero weather. Eventually I ended up in Berlin in the midst of allied bombing.

In the meantime, I had lost track of my entire family; however we were later reunited. When the Russians occupied Berlin I tried to survive by returning to my home town. Due to lack of transportation I had to hide myself on freight trains. After much hardship I reached my hometown, only to find it occupied by the Russians. I was sent to a forced labor camp with the rest of the civilian population. People in the camps were dying in great numbers from disease and mistreatment.

How did you manage to survive in such conditions?

In the midst of all this, I found solace in my childhood visitations of saints, and came to understand the meaning of prayer. In it you have an object of concentration (I called it God at the time), and trust is developed. You know you have help and think it comes from outside, but even then I also realized it comes from inside.

Like all other young women in the camp, I was subject to repeated rape; however, I found I had no animosity or anger against these occupying soldiers. I had a tacit sense that I was one individual recipient of a collective karma brought on by my entire country. Although I did not personally contribute to its causation, I realized that as a member of that society I must share in experiencing the consequences.

Perhaps you had some precocious understanding of karma at the time?

I was not in touch with that then, of course. I was unaware of the concept. But I somehow knew that if I did not hate anyone God would save me and somehow make my condition better. And it did happen. I got some form of help wherever I went. Its a wonderment when I think back to these difficulties that I am even here now.

In one camp I was assigned to the household of a Russian officer as a domestic servant. I still wanted to get to Berlin, so I escaped from that camp and hid in the undercarriage of a freight car. At one point I was discovered by a Russian soldier and subsequently found myself peeling potatoes for the Russian occupation forces. At this time I became severely ill and was put into a hospital. One of the doctors was very kind to me, but he had thoughts of marriage. I escaped again by jumping from his carriage on a rainy night, and after more hardship and abuse I reached Berlin.

Later I managed to secure a teaching position in West Berlin. Through a teacher’s organization I made contact with teachers in America, and after a time I was fortunate enough to have someone offer to sponsor me if I wished to come to the United States. I settled in Los Angeles, went to college, and through a circle of friends in 1958 met the man who would become my husband.

Was it through your husband that you got interested in Buddhism?

Before we married my husband had been an ordained Vedanta monk for some years, but had left the temple. He was a friend of Alan Watts and eventually we both became interested in Zen. Our home became a central meeting point for others with similar interests. It was not uncommon to find a Fritz Peris seminar or Lama Govinda at the house.

And how did you wind up in Burma?

In 1960 my husband wanted to experience other approaches to meditation. We spent some time in Japan at Zen monasteries, and then continued on to the Phillipines, Hong Kong, Singapore, and eventually Burma. In Burma, we practiced at the Mahasi Sayadaw monastery. I discovered that I had a natural affinity for staying in touch with my body. Even though I suffered from back problems which made sitting extremely painful, I was able to stay in touch with my bodily sensations and began to enjoy ever deeper levels of concentration.

After leaving the Mahasi Sayadaw monastery we went to the meditation center of U Ba Khin, who spoke English and could provide a more comfortable learning situation. He became my teacher. At this time I was experiencing a lot of resistance to being in Burma. I was worried that my husband would become a monk again, and I innocently felt also that I was satisfied with my inner life and I already knew the things U Ba Khin was teaching (I had previously had sensory awareness training with Charlotte Selver.) But I did persevere and my meditation practice with U Ba Khin was a breakthrough experience. U Ba Khin emphasized awareness of bodily sensations. I opened to a deeper level of samādhi [concentration] and to a more correct understanding and comprehension of what was happening in the mind-body system, as well as to the genuine purpose of meditation.

Did you stay long with U Ba Khin?

We stayed about three months (visa restrictions did not allow a longer stay), then we went to India. We stayed at the Ramakrishna temple complex in Calcutta where I enjoyed devotional practice. When we returned to Los Angeles I became very involved with Zen practice as there was no opportunity to carry on vipassanā practice; it was, for the most part, unheard of in the West.

In the mid-60’s we returned to Japan and stayed a year, training more seriously with Yamada Roshi and Soen Roshi, and also with Yasutani Roshi.

How did Zen practice suit you?

Although the sesshins were quite rigorous, I grew to like the discipline they required. I found the concentration on the Mu koan disconcerting. Concentration was very forceful and led to temporary states of separation between me and my body. Soen Roshi encouraged me to return to my vipassanā practice. He taught me shikantaza [“just sitting”] practice, which balanced my energy and healed my condition.

I had some training in sensory awareness and I put it to some intuitive use.

When I then returned to Los Angeles a rich period of spiritual practice began. I kept in close touch with Maezumi Roshi’s Zen Center, and with Sasaki Roshi who was starting a zendo. I offered my house for fund raising benefits to build those zendos and also as a place for spiritual teachers to hold darshans, pujas, and lectures. I found myself often in the role of cook and hostess. My living room became a great birthplace for spiritual investigation.

And what about vipassanā?

I continued with my vipassanā practice during the hours of sitting in the Zen Centers. I returned to Burma three or four times after my initial practice with U Ba Khin, but could only stay for short periods. Once I stayed for six days and that was a deepening experience for me. My teacher died in 1971.

Did you ever get some formal transmission from him?

Yes. U Ba Khin had founded an international meditation center. At the time I was there, he gave transmission to teach to only four or five Westerners, and of those, to only one woman. I was that woman. He wrote me a letter as a formal document for receiving the seal of Dharma to teach. I remember him touching the tip of my nose as I was leaving and saying, “May this be your best friend.”

At that time I didn’t really know how to acknowledge the transmission. I felt I needed more training. U Ba Khin encouraged me to proceed and told me not to worry, that I was “a natural,” and that the practice would guide me.

And so you started teaching…

In the early 70’s I was in Switzerland, attending a Krishnamurti seminar.

While there I got a message from Robert Hover, who had also been given transmission by U Ba Khin, inviting me to teach a retreat with him in Frankfurt. I subsequently was asked to teach in France, England, and Switzerland. Then I did a number of courses all over Europe, from Spain to Norway and Sweden. For the next four years, I was on the road teaching non-stop. Looking back I realize that I started vipassanā in all those countries, and really did the ground breaking for all that followed.

At what point did your center, Dhamma Dena, come into existence?

I never intended to have a retreat center, let alone in the middle of the desert. In 1977 I purchased a cabin on five acres outside of Joshua Tree, California. I often used it as an escape from Hollywood. My students just followed me there and it began to grow.

At one point, Mahasi Sayadaw came with his retinue of monks and gave his blessing to the center. At that time the zendo was an old garage with a sand floor. Over time we acquired additional buildings and land. We now have comfortable but rustic accomodations and a 360 degree view of mountains and desert. We also have several small cabins that can be rented. Students may come for formal or self-retreats.

I encourage people to gointo their difficulties and cope with the change that’s taking place.

As we grew, occasionally other teachers would also use the facility. We host a month-long Zen sesshin each year. Since I do not travel to Europe much anymore, I live at Dhamma Dena full time. We have six to eight people who live as a sangha. There are always a few students from Germany, and a number of students have bought houses or cabins nearby, so there is an extended sangha.

You do not seem to teach vipassanā in the usual way—silent sitting and walking with an occasional Dharma talk. Can you say anything about your methods of teaching?

As I mentioned earlier, U Ba Khin (my teacher) stressed awareness of bodily sensations. Each of the teachers in his or her own time develops their own emphasis within the awareness of bodily sensations. Some stress hearing, others sight, etc. Some teachers utilize only sitting. U Ba Khin taught and practiced the development of awareness only in strict sitting—with only very short informal periods of walking meditation.

The longer I taught, the more I realized the difficulties that the meditators displayed in their meditation; they did not have the cultural and religious background for the ability to simply sit and pay attention to their own living process, body-mind sensations. In focusing so intently on the breath and body parts for long periods of time, people would try too hard.

So I expand the selection of body sensations to keep the meditators engaged, and to foster softness and gentleness within themselves. I experiment with the application of mindfulness to body, breath and sensations in body positions other than just sitting. What evolves is meditation while standing, walking, running, jumping, lying down, rolling on the grass—meditation in the entire scope of body’s mobility and expression, in yoga āsanas, in dance and laughing, in sound, touch, taste, sight or imitation motions such as crawling like a worm, etc.

But let me stress that what I do is strictly within the prescribed bounds of Buddha’s teachings—using the body and its sensations as a vehicle for mindfulness training, for developing awareness for clear comprehension of the present moment, of correct understanding of life’s living and dying.

By using such variety of sensations for developing awareness students learn how to apply their practice in situations other than simply sitting on a pillow. Often students do not know how to carry practice home with them after a retreat. But awareness developed in such a wide scope of meditation pattern, as I teach it, becomes gradually a natural state, and for that reason it is effortless and not easy to lose.

The kinesthetic sense is corrected by means of movement, the focusing ability more easily strengthened than in strict sitting, and ease and relaxedness in body and mind is naturally invited. Often, however, students fail to recognize the fact that these psychological exercises or meditation in expression are actually part of the First Establishment of Mindfulness [in the Satipaṭṭhāna text]. So, in truth, I am not teaching a different version of vipassanā meditation. I feel it is rather the extended edition.

And you offer your students more guidance than is usual, don’t you? I believe the IMS course description refers to “sustained and on-going verbal teacher instruction throughout the day.”

I do feel that this description of verbal guidance is slightly exaggerated and misunderstood, for I do give or allow sufficient time for the meditators to practice by themselves, on their own, and without instruction.

As we know, there are many obstructions and difficulties in our meditation practice. So my so-called “ongoing verbal instructions” are one way of alleviating or easing these difficulties the students suffer in their sitting meditation. So instead of insisting upon the traditional meditation pattern of sitting for a full hour with only a few moments’ interruption, I include verbal support during quiet sitting practice as a natural reminder for returning from daydreaming or lost-thought-processes to mindful attention to the meditation object proper.

I provide verbal support during the sitting meditation also for the purpose of perhaps quicker recognition of the student’s alertness or sleepiness, or for realizing and knowing what is happening in one’s emotional or thinking level.

Clear comprehension—a mental ability to discern and know the present situation clearly and fully—is part of mindfulness and therefore very much enhanced through verbal assistance during the quiet practice as well as during any kind of practice in motion. In this way, as one student told me, “self-correction and self-observation can occur on the job.”

I also use verbal assistance as encouragement for perseverance in the vipassanā practice, or as reminders for self-examining the quality of attitude and effort.

Practicing in these various modalities within the vipassanā meditation features an outstanding quality— “Never a dull moment,”—and a demand for total participation from the students and the teacher. This in turn cultivates a wonderful spirit of genuine communion.

Most of all, I encourage people to go into their difficulties and to cope with the change that’s taking place even as they are paying attention to it. Our life is nothing but change and it is to this change that I bow deeply. I bow to this change, I bow deeply to life itself.