Q: Bhante, in the first part of our interview you described your first encounters with meditation and how you went to Asia and took temporary ordination, until you had to go back to Germany to settle things. What happened next and how did you get ordained again?

Q: Bhante, in the first part of our interview you described your first encounters with meditation and how you went to Asia and took temporary ordination, until you had to go back to Germany to settle things. What happened next and how did you get ordained again?

A: Back in Germany I settled what needed to be done and also worked a bit to replenish my travel funds. Then I went to China, in accordance with my original plan. I studied Chen-style Taijiquan and also spent time at a Chan monastery in Hong Kong. In addition, I went to Tibet, where I experienced Buddha Purnima, or Vesak, celebrations in Lhasa, circumambulated Mount Kailash, and visited Milarepa’s cave, which was for me especially meaningful.

Then I went to Sri Lanka with the idea of getting ordained again. I had been a vegetarian for a long time and maintaining that had not been easy as a monk in Thailand. I was told that there had been a dissident movement in the Thai Saṅgha, Santi Asoke, which among other things adopted vegetarianism. As a result, vegetarianism, especially if adopted by monks, had acquired a bad reputation. In contrast, in Sri Lanka this is unproblematic, and many monks of the forest tradition are vegetarians.

In addition, I wanted to meet Ñāṇaponika Mahāthera, as reading his book, The Heart of Buddhist Meditation,had a profound impact on me. Unfortunately, when I arrived at Colombo airport, I was told that he had passed away just a few days before.

Since I had been recommended to go to Nilambe Meditation Center, I went straight there from the airport. The meditation teacher was Godwin Samararatne, and he had a major influence on me with his kind and openly receptive style. Central here was his mettā, and it was after meeting him that I finally made some progress in this meditation practice, after relinquishing the approach of relying on phrases. This had never worked so well for me, as due to my personality it tended to get me up into my head. By learning just to open my heart, the mettā meditation finally took off for me. Later I discovered that the standard approach of using certain phrases directed to specific people is in fact not found in the early discourses. This made me realize the importance of adopting a historical perspective on Buddhist teachings.

Godwin knew I wanted to get ordained again, so he arranged for me to receive the precepts from Balangoda Ānanda Maitreya Mahāthera. During my time as a monk in Thailand I had gotten quite uptight about keeping the rules that come with full ordination, so this time I decided I would remain a novice for a while to avoid such problems. In the end, I remained a novice for twelve years and only then took higher ordination, which Pemasiri Mahāthera kindly facilitated.

Q: How did you become involved again with academic study?

A: That was also something Godwin organized, though in this case without me wanting it or even knowing what he was up to. My own expectation had been that, once ordained again, I would do full time meditation practice, similar to the time when I lived in a cave in Thailand. But he had the idea that I should pursue Buddhist Studies at the University of Peradeniya and do research on mindfulness. He had it all set up with the professors before even telling me, and with his kind and gentle ways overcame my resistance. When I finally agreed, I decided that I would nevertheless make sure my meditation practice did not suffer by determining that I would only spend the first half of each day in studies and for the second half retire to my hut to meditate. This worked out quite well.

The hut in which I was living was at the back of Udawattakele Forest, within easy walking distance of the Forest Hermitage, where Bhikkhu Bodhi was living. While doing my studies and research on the Satipaṭṭhāna-sutta, which had become the topic of my Ph.D. thesis, I would regularly go to visit him, and he kindly took on the role of guiding me in the study of the Pāli discourses. He had given a series of talks on these at the Buddhist Publication Society, and I got hold of the numerous recordings and listened to all of them. Together with my questions that he patiently answered, this laid a good foundation for my understanding of the Pāli discourses.

In addition to benefiting from his tuition, I also had regular meetings with Bhikkhu Kaṭukurunde Ñāṇananda. In his lay life, he had been an academic in the field of Buddhist Studies, but then he took robes and went to live at Nissaraṇa Vanaya, a forest monastery dedicated to intense insight meditation. During his stay, he had given a series of thirty-three talks on Nibbāna in Sinhala, which had been recorded and subsequently published. He had just started translating the first of these talks himself into English, and Godwin had passed on the tape for me to listen to. I was thrilled by the depth of his exposition and immediately went to visit him in the cave in the Kegalle area, where he was staying at that time, to put myself at his disposal. I suggested that he continue translating his talks, and I would take care of the rest.

So I regularly received the latest tape with his translation, transcribed the talks, and then searched for and supplied references to the Pāli originals. He had an amazing memory and could quote all these passages in Pāli, so my task was to find their location in the Pāli texts. Working with these talks had a deep impact on me, and I regularly visited him to get some points clarified or just for Dhamma discussions.

In this way, what officially was a Ph.D. research became a way to immerse myself in the teachings of the Pāli discourses, under the kind guidance received from Bhikkhu Bodhi and Bhikkhu Kaṭukurunde Ñāṇananda.

In addition to these two, Bhikkhu Ñāṇadīpa also had a deep impact on me. He lived a very solitary life, so it was not possible to have regular contact with him, but the meetings I did have with him, together with his exemplary lifestyle and thorough acquaintance with the Pāli discourses, have been a strong source of inspiration for me. For some time, he only allowed visitors on three full-moon days in the whole year. He just lived out in the open in the forest by himself. If villagers offered to build him a hut for the rainy season, he would only accept the simplest construction, and it should have only three walls, so that one side was left open and he could remain in constant contact with the forest. He did not even use a mosquito net. When I asked him how he managed without any protection against mosquitos, he replied: “After about three years, you don’t feel it anymore,” adding that with some of the biting ants that live in the Sri Lankan forests, it takes longer than three years. I found his renunciation deeply impressive and feel very fortunate to have met him.

Q: What motivated you to return to the West?

A: The main motivation was repaying the debt of gratitude to my parents, otherwise I would have stayed in Sri Lanka. By then I was in charge of a small meditation center on the outskirts of Kandy, had finished my Ph.D., was regularly teaching meditation, and was otherwise happily living the life of a meditating monk. No reason at all to leave a wonderful place like Sri Lanka, the country with the longest history of Buddhism in the whole world.

However, my parents had retired, and it became clear that they would greatly benefit from my presence. After some initial resistance, particularly by my mother, they had accepted my becoming a Buddhist monk and were even slowly opening up to the possibility of doing a bit of meditation. They were able to provide me with the basics needed to continue my monastic life in Germany, namely offering me food every day and letting me stay by myself in an annex to their house, so I decided to go. Originally, the idea was just to stay there for a while and then return to Sri Lanka, but that stay became much longer than I had originally expected.

I shifted from doing retreats half of the day to doing them half of the week: at first, three days per week and then four days. My life with them was already rather secluded, as I did not connect much with Western Buddhists. My whole experience of Buddhism had been in Asia, and I had difficulties bridging the cultural gap. So I chose to keep to myself, as I felt a bit like a fish out of water. It took me quite some time to bridge that gap between the traditional form of Buddhism I knew from Asia, which, in spite of my Western upbringing, I felt to be my spiritual home, and Western approaches to Buddhism.

Q: How did you get involved with comparative studies?

A: My mother wanted me to continue my research activities by doing a habilitation thesis, which in the German university system follows after a Ph.D. and is the basis for becoming a professor, and this time I did not put up resistance to pursuing academic study further. By now I had realized that good knowledge of the teachings, in particular adopting the historical perspective, can be of considerable support to meditation practice.

In the course of my research on the Satipaṭṭhāna-sutta, I had come across information about the Chinese parallels, so at the completion of that research I was left with a curiosity about these parallels. I got in contact with Bhikkhu Pāsādika, who facilitated me doing habilitation research at the University of Marburg. Since the Satipaṭṭhāna-sutta was in the Majjhima-nikāya, it was natural for me to choose the whole collection for a comparative study as my habilitation thesis. This then led to a large number of discoveries and publications.

Q: How did you come to the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies (BCBS)?

A: Bhikkhu Bodhi had returned to live in the US and was staying in a Chinese monastery in New Jersey, so I visited him there. Joseph Goldstein had sent a message that he would like to meet if I should ever be in the area, so I went to BCBS to give a talk there, and we met and quickly became friends. I started to teach courses at BCBS and also at Spirit Rock, the Insight Meditation Society, and Forest Refuge, sharing my approach to meditation based on what I had found in my research.

It took a while for me to learn how to present my practices in the West, as the way I had been teaching in Sri Lanka was quite different. But once I managed to bridge the gap, things went well. I particularly like BCBS, situated as it is in a triangle with the Insight Meditation Society and Forest Refuge as two places offering the opportunity for deep meditation practice. In that setting, BCBS can provide an important input from the teachings that can orient and deepen meditation practice. This is precisely what I also hope to offer to the growth of Dharma in the West, so BCBS is in a way a perfect fit for me.

Q: Can you describe the meditation practices you teach?

A: There are basically four practices that build on each other, all of which are grounded in an embodied form of mindfulness that is open and receptive.

The first combines the four satipaṭṭhānas into a continuous meditation, based on those exercises that stand out as the common core between the Satipaṭṭhāna-sutta and its Chinese Āgama parallels: Contemplation of the body comprises just the anatomical parts, elements, and a corpse in decay, the last of which I use to introduce the all-important recollection of death. Then contemplations of feeling tones and mental states, leading up to a cultivation of the awakening factors as the fourth satipaṭṭhāna.

The second practice concerns the sixteen steps of mindfulness of breathing, based on the understanding that this practice is not about just focusing on the breath to the exclusion of everything else but rather about using the breath as an anchor to explore various aspects of subjective experience (mirroring the four satipaṭṭhānas, in fact).

The third practice is cultivation of the four brahmavihāras, the divine abodes, where my approach is based on reducing the use of phrases and concepts to a minimum in order to be instead with the direct experience of each of these four abodes. Abiding in mettā, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity then takes the form of a boundless radiation in all directions.

The fourth practice is emptiness meditation, based on the Shorter Discourse on Emptiness, number 121 in the Majjhima-nikāya. Although my approach is firmly grounded in early Buddhist thought, I greatly benefited from practicing in the Mahāmudrā and Chan traditions. In fact, as an aside, it was Godwin who took me along to Nepal to meet Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, from whom I then received the pointing-out instructions. These had a profound impact on my practice.

So the way I teach emptiness follows the progression in the later part of the Shorter Discourse on Emptiness: infinite space, infinite consciousness, nothingness, and signlessness. Signlessness in particular seems to have much in common with both Mahāmudrā and Silent Illumination in Chan practice. Based on previous training in satipaṭṭhāna, mindfulness of breathing, and the brahmavihāras, the practice of emptiness can fully unfold its liberating potential.

These same practices are also what I do myself. Since coming to live in the US, I shifted from four to five days of retreat per week, and right now I am transitioning to six days per week. In addition, I also do longer periods of continuous retreat. I plan to continue to teach a little bit and still do a bit of writing, though much less than I have been doing up to now, but what I mainly hope to do with however much time remains for me is just to live the quiet life of a meditator.

Q: Thank you, Bhante, for the interview.

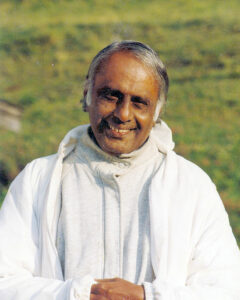

Bhikkhu Anālayo is a scholar-monk and the author of numerous books on meditation and early Buddhism. As the resident monk at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies, he regularly teaches online study and practice courses and undertakes research into meditation-related themes.

A pdf version of this interview can be downloaded here.