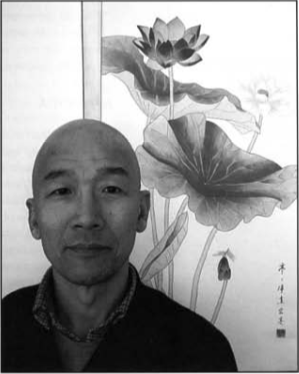

An interview with Issho Fujita

For the last eighteen years, Reverend Issho Fujita has been the resident teacher at Pioneer Valley Zendo, a Soto Zen practice center in Charlemont, western Massachusetts. He has taught a weekend retreat on Dogen Studies at BCBS each year for the last ten years. He has recently decided to move his family back to Japan. The Insight Journal talked with him about his hopes and aspirations in such a move.

Would you talk a little bit about what it was like growing up in Japan and how it connects to your interest in Buddhism?

I was born in 1954 and my parents did not belong to a Buddhist priestly family, as is usually the case with Japanese people who become Buddhist priests.

My father was a salary man, my mother was a nurse, and we all lived with my grandparents. I thus grew up in a very typical Japanese household.

Like most Japanese families, we followed Shinto and a form of Buddhism which, in our case, was the Shingon sect. For Shinto ceremonies, my grandparents would come out each morning, face the rising sun, clap their hands and bow their heads. Then they would come inside and do the Buddhist ceremony, which consisted of changing the water, tea, and rice on the small family altar and cleaning it. They would chant a short dharani [protection formula] from the Shingon tradition. Of course, they didn’t know what the dharani meant or even why it was done. My grandparents knew few historical facts about Kukai [the ninth century founder of Shingon Buddhism], but they believed him to be someone like a god. They did not even know that Shingon was an esoteric school of Buddhism. For them Shingon was a religion all by itself.

Growing up in this environment, I had no serious connection with Buddhism or Buddhist teachings. Then at the age of ten I had an experience which seemed to change my life. I was riding my bike when I looked up and saw the sky filled with stars. I was struck by the realization that I was just a tiny, tiny dot in a vast universe. The realization that “I’m here as a speck of dust” seemed overwhelming at the time. It triggered in me some serious existential questioning about the meaning of life.

I started reading books about philosophy and science; I wanted to know what the “original universe” was. By the time I graduated from high school at the age of seventeen, I was going through an existential crisis. In my high school year book, I wrote that I would rather be a skinny Socrates than a fat pig. This was my attempt to say that I was not interested in getting an education for the sake of getting a job, but that I wanted my life to be changed.

My interests throughout my high school years had been in hard sciences, but when I was studying to enter Tokyo University I changed my interest from science to philosophy. Tokyo University is the Harvard of Japan. When I chose the philosophy track, over law and economics, my parents were really disappointed, because they thought I was throwing away an opportunity for getting prestigious jobs and positions. But still their disappointment did not produce a big family conflict.

What was your experience at Tokyo University like?

There was mainly an atmosphere of apathy all around. Japan was going through its own particular process in the post-war years, when prosperity was on the rise but Japanese people were not sure of their own identity in those rapidly changing times. Over a period of time, I changed my focus from philosophy to psychology. I took courses in Freudian psychology, because I was very interested in what Freud had to say about the unconscious and what it might mean for inner transformation. My interests at that time were in clinical and developmental psychology. I also became very interested in Aikido and body movement.

After completing my undergraduate degree, I entered the graduate school at Tokyo University and stayed there for five years, completing a Masters degree and enrolling in a doctoral program. But that seemed to be a dead end. None of it seemed to provide any answers to the deeper problems of human existence, and I felt quite frustrated.

It was at that time that I met a teacher of Chinese medicine. This particular discipline was originally from China but had been modified according to Japanese patterns. This teacher was also a student of Rinzai Zen, and he told me that in order to be a healer or a doctor you have to known yourself very clearly. At his suggestion, I did a seven-day winter sesshin [meditation retreat] at Enkakuji temple in Kamakura. I had no background or preparation for such an intense sesshin, and it was really hard both physically and psychologically. But I was very impressed with the practice, so I continued to attend the sesshins at Enkakuji. And also I attended weekend zazen [sitting] gatherings at a temple in Tokyo for about a year. I became interested in the idea of becoming a monk at this time, and through karmic connection, I finally visited Antaiji Temple to check it out. I decided to stay there to practice full time.

Tell us something about the history of Antaiji Temple.

Antaiji was actually founded and funded in the 1920s, outside of Tokyo, by a lay person who wanted it to be a place for scholar-monks, primarily graduates of Komazawa University in Kyoto, which was then a Soto Zen school. During World War II the temple was largely abandoned. Sawaki Roshi used it as a resting place during his travels. When my teacher, Koho Watanabe, inherited Antaiji from Koho Uchiyama Roshi, the dharma heir of Sawaki Roshi, he decided to sell the temple and buy a whole village in the north, in the snowy country of Hyogo prefecture. This village had also been abandoned, so they were able to purchase a huge area of land with the money they got from selling the urban temple. The new Antaiji was established in the early seventies under the leadership of Watanabe Roshi. It followed the lifestyle of Ch’an schools from old China, with the monks growing their own food.

Most people try to fit Buddhist teachings into their existing ideas.

Antaiji is not a certified monastery of the Soto Zen establishment, which means it has nothing to do with priestly qualifications. It had to survive on its own. There were an average of seventeen to eighteen monks during the six years I stayed at Antaiji. It was a practicing community, and there were quite a few Westerners too. Then my teacher asked me to go to a monastery in Kyushu for one year and be the training monk there. But soon after my arrival in Kyushu I got a call from my teacher asking me if I wanted to go to America and take care of a temple there. It took me about ten seconds to think about it and say yes. I arrived at Charlemont in July, 1987.

What was the idea behind sending you to America?

The Pioneer Valley Zendo had been established about seventeen years earlier by the collaboration of Antaiji and American Zen practitioners, and there had been three monks from Japan who had been resident teachers here. So there was a tradition of a Japanese monk as a practice leader at Valley Zendo. When the monk before me decided to leave Valley Zendo, my teacher asked me to take over the responsibilities here. There was no specific plan, except to just live here and be a practice leader.

What did you find when you arrived?

There was already a small sangha here, so it was a smooth transition. We would have at least seven or eight people for day-long sittings each Sunday. Taitetsu Unno, who was then a professor at Smith College, also came to greet me, and he asked me to lead weekly sittings at Smith College.

It was all very new to me. I had never been in the position of a teacher before. But the transition was made easier by the fact that Valley Zendo was a place of practice. So I could lead practice sessions through my own example. Giving talks was hard, because I had not done this before. Also, I had to give the talks in English, which meant having to learn how to translate Japanese words into English in a way that conveyed the spirit of practice. It helped that I was giving talks to seasoned practitioners, which made it easier to convey the spirit to them. It was perhaps somewhat more difficult in weekly sitting at Smith College, and later at Mount Holyoke and Amherst colleges.

You have personally been greatly inspired by Dogen’s teachings. How were you able to include those teachings in your talks or teachings?

This happened primarily at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. The format of the weekend workshops here was quite different from the practice sessions at Valley Zendo, and it was designed to add a scholarship element to practice.

So it has been enjoyable and valuable for me to come here each year and share my understanding of Dogen with other people.

In your teachings you have laid great emphasis on the posture in zazen practice as well as body movement. Can you talk about it some more?

As I have said earlier, I was interested in Aikido and other martial arts when I was a student at Tokyo University. In the practice of shikan-taza [just sitting], there is so much emphasis on posture that it excludes everything else. One way to express this is to say that shikan-taza practice is physical rather than mental. In other words, breakthroughs comes in the body rather than through words. I have always been interested in the physicality of Zen practice. This aspect has been neglected in Japan, and I have been interested in digging out this neglected aspect and re-incorporating it in my teaching shikan-taza.

The Buddha’s teachings are revolutionary–they challenge both the social and scholarly Buddhisms of Japan.

After some years at Valley Zendo, I took courses in various body-based therapies such as the Alexander and Feldenkrais methods. It has helped me to understand more deeply the musculature of the body, and how a correct understanding of zazen posture must involve this kind of knowledge. I am inspired to translate the physicality of Zen into new language. As I said earlier, for me the spirituality of Zen is its physicality. That’s why sitting upright is so important. It allows for the breath to circulate freely in the body. This free circulation of the breath is the basis of all healing. This is perhaps an old idea from yoga, and I am trying to find “spiritual” breakthroughs in and through the body. For example, “letting go” should be understood not only as a psychological quality but also as a physical one. I believe it cannot be truly realized without attaining “somatic letting go,” which is a kind of relaxation at the deep core of the body.

Talking of spiritual things, what has been your experience in working with practitioners in America?

One of the things I found over and over again is that most people want to know how to handle their emotions, especially anger. This concern is not predominant for Japanese practitioners, and it was a challenge for me how to respond to these concerns. I think dealing with emotions was also the largest issue for undergraduate students when I taught weekly sittings at the local colleges. There seemed to be a strong tendency among them to take everything too personally.

In other words, they tend to believe that they can and should control everything. This makes their life harder, sometimes unnecessarily. Zazen can be a counter balance against this tendency.

In moving back to Japan after eighteen years in America, what do you expect to find there, both easy and difficult?

I like to think that I am returning with a broader perspective than I left with eighteen years ago. In Japan, there is a stereotypical image of the priest which will be very hard for me to deal with. A priest is a person who owns a temple, has a congregation, and has a social role to play in his community. I have no interest in being a temple priest. I never had that interest. Yet when I go back there I will still have a shaved head and priest’s clothes, even though they are working clothes and not fancy robes. It will be hard to explain to people where I fit in. The entire Japanese society is built around people fitting in a particular slot. It is not comfortable for people who don’t fit in.

The temple priests use an old-fashioned language when speaking of Buddhism, which appeals to their own congregations but turns off younger people who have gone through a secular education. I hope that somehow I can speak to these younger people in a language that is meaningful to them and that addresses the real problems of their life.

What are your thoughts of the New Buddhism or Critical Buddhism in today’s Japan?

The problem of Japanese Buddhism seems to be that there are only two kinds of participation: social or scholarly. By social I mean the function of the temple priest in his congregation, mainly performing the funeral rites. The other side is the scholarly person who just writes about Buddhism in a university setting without any real engagement with the problems of life.

The movements calling themselves the New Buddhism are not really changing anything. They are creating new congregations, mainly in large cities, but are providing the same kind of structure that a temple priest does in his village temple.

But the Buddha’s teachings are revolutionary—they challenge both the social and scholarly Buddhisms of Japan. There is a need in laypeople for what the Buddha is teaching, and I believe they are open to these teachings if someone can talk to them about how they can address the problems of their life. The big challenge of Japanese Buddhism today is how to organize a response to the real needs of the people.

Can you give us some idea of how you want to present your own response?

I believe there are two gates to Buddhist practice: deconstruction and reconstruction. Most people try to fit Buddhist teachings into their existing ideas. They are using Buddhism to express what they want to believe. This is equally true in both Japan and America. In America, people are trying to reconstruct Buddhism according to their own ideas, but they are not really interested in first deconstructing their own assumptions. People are looking for a quick fix, when the change required is at a fundamental level.

The Buddhist term soto in Soto Zen means “sweeping out” or cleaning up the old. Before you build a house, the work of cleaning up or clearing the ground needs to be done. We need to change the basic assumptions about life itself.

But neither temple priests nor Buddhist scholars in Japan are doing this. The social movements of Japanese Buddhism don’t see the necessity of drastically changing ordinary thinking. They do not address the basic anxieties people feel about life, and are thus losing their appeal.

I hope people interested in Buddhism get excited by the deeply creative possibilities in these teachings.

I think the material success in Japan in the postwar years has been quite confusing. People’s lives have lost their focus and meaning. Many people feel an emptiness in their life, but they don’t know how to fix it. Buddhist teachings have a lot to say about the meaning and purpose of life, but the solution is not in just creating another organization. Even when people speak about Buddhist ideas and the vocabulary is there, it’s mostly an empty sound because people don’t have an idea of what’s behind the vocabulary.

I have found that even the community of priests in Japan is unable to talk about these basic problems. So it has been impossible for me to join them in any organizational sense. My teacher said often that being a Buddhist means to be critical of the mainstream culture.

This was the Buddha’s own situation, as an outsider to mainstream culture. When Buddhism becomes mainstream, something goes wrong. I am not afraid of being an outsider, and I want to take my chances in what kind of difference I can make back in Japan. It may be that I will sound like a stranger, because so much has happened and changed in my own thinking during eighteen years in America. I am ready for this difficulty. At the same time, I am excited about my new life and its possibilities.

How do you plan to incorporate your interest in Dogen scholarship into whatever you do in coming years?

I am not very ambitious, and I don’t want to create a personal agenda. My interest in Dogen has always been personal, in the sense that this scholarship is not central to how I teach zazen and shikan-taza. But it has always been greatly stimulating for me. My association with BCBS has deepened my interest in vipassanā [insight meditation] and Pali traditions, and I see Dogen reflecting these earlier teachings in so many different ways.

Even though Dogen has such a great mind, his interest is first and foremost in the authentic practice. So when I read the Pali suttas [discourses], especially the Sutta Nipata, I hear echoes of Dogen in it; and when I read Dogen, I hear echoes of the Sutta Nipata. For me they become mirrors of one another. Reading the suttas helps me understand Dogen a little better. Even though Dogen did not have access to Pali texts, my sense is that he fully understood the message of those early texts and was inspired by them.

Do you have final thoughts for the readers of the lnsight Journal?

I find it inspiring that today we have access to all Buddhist texts, and there is a possibility of an integrated learning of Buddhist teachings for anyone who is interested. We don’t have to be entrapped by sectarian or cultural views of Buddhism. We can rise above them. It’s possible to get access to DNA, so to speak. Dogen distilled the entire Buddhadharma into one single theme of “just sitting.” That was his way of changing the DNA. Today there are even more possibilities of doctrinal refinements. I hope people interested in Buddhist teachings have a deep curiosity. I hope they get excited by the deeply creative possibilities in these teachings, rather than exploring them as a mere hobby or idea.