The present article explores the intersection of and distinction between Christian and Buddhist practices of Insight Meditation.

Introduction

Within the wider field of interreligious dialogue between Christianity and Buddhism, an intriguing arena of investigation is the degree of similarity and difference between Christian and Buddhist forms of meditative contemplation. Forays into this arena have been considering in particular two eminent saints of the Carmelite tradition in Spain, the sixteenth century St. Teresa of Jesus (commonly known as St. Teresa of Ávila) and St. John of the Cross, comparing their writings with a chief exponent of Theravāda thought, the fifth century Indian monk Buddhaghosa.

In the context of a study of the stages of mysticism described in St. Teresa’s Interior Castle and the stages of purification in Buddhaghosa’s Path of Purification, Cousins (1995: 114) highlights the similarity between levels of Christian prayer and stages of Buddhist absorption, concluding that “both are ecstatic trances involving immobility of the body and the suppression of many of the ordinary mental activities. Both are characterized by peace and joy.” Alongside noticing such similarities, however, Cousins (1995: 103) also expresses a critical attitude toward perennialism, stating that “I am convinced that to think of a single transcendental mystical experience is in certain respects misleading.”

Millet (2017 and 2019) explores the same similarity between St. Teresa and Buddhaghosa, presenting a more finely grained and detailed comparison between Carmelite prayer as described in the Interior Castle and Buddhist absorption as described in the Path of Purification. Millet (2019: 7) offers the following comment:

Notwithstanding the similarities, it is equally important to note the no less significant divergences between both systems, and their opposing and even conflicting viewpoints. In a number of their most fundamental beliefs, both traditions are mutually exclusive. They are embedded in different philosophical and theological milieus and, therefore, encompass differing discourses and even opposing views. They likewise provide unique maps borne of the singular exploration of the territory they describe, and they belong to different ages and tongues, having been bred in unconnected religious-cultural cradles, with disparate socio-economical and historical backgrounds.

In a study of St. John’s writings in light of descriptions of Buddhist absorption, Harris (2018: 78) reasons that “the differences in the metaphysical underpinnings of the goals of spiritual practice in each [tradition] must not be overlooked: a personal God and an impersonal nibbāna.” At the same time, however, she could not “help speculating that the experience that Christian mystics call union with the love of God is not so very different from the experience of absolute wisdom and compassion that Buddhists call nibbāna.”

In this way, alongside a general agreement on substantial differences in metaphysics, there is at times a sense that between the two final goals there could be a close phenomenological similarity, if not identity.

Christianity Looks East

In a monograph titled Christianity Looks East, Feldmeier (2006) presents a survey of the respective paths to holiness and final goals advocated by St. John of the Cross and Buddhaghosa. Feldmeier (2006: 44) warns that, in spite of similarities,

the philosophical differences between these two spiritual systems should not be marginalized or readily dismissed … how we understand our very nature affects how we proceed in the spiritual life and how we interpret our experience … there is an enormous difference between believing oneself as made for love and believing oneself to be no-self at all.

Comparison of the respective paths leads Feldmeier (2006: 72) to finding similarities but also differences between the two traditions:

There is a central quality in the experience of the path that radically differentiates them … in Buddhist spirituality … love has only conventional value; it has no ultimate reference … when we compare this with John’s contemplative agenda, we see quite a striking difference. Love takes on absolute importance.

Feldmeier (2006: 73) sums up that “John’s is a mysticism of love, while Buddhaghosa’s is one of deep, penetrating, impersonal insight. In this regard, they cannot be farther apart.” The same basic difference then plays out in relation to the final goal, leading Feldmeier (2006: 91) to the conclusion that “Nirvana and God are not the same realities.”

In view of similarities between the two traditions, Feldmeier (2006: 112) is in favour of Christian practitioners employing Buddhist meditation practices, in particular the cultivation of mettā (often translated as “loving kindness”). In relation to insight meditation, however, Feldmeier (2006: 108) expresses reservations:

Buddhist insight into selflessness can be perfectly valid for Christian self-emptying as long as one retains the proviso that there is a great difference between John’s detachment as it renounces objectifications of the self and Buddhaghosa’s absolute deconstruction of the self. The deconstruction of the self in Buddhism, while sharing the agenda of breaking narcissism, also has the agenda of reducing the soul to an impersonal collection of aggregates. This latter agenda cannot be incorporated vigorously without undermining Christian spirituality.

Insight Meditation

In line with the endorsement of mettā meditation by Feldmeier (2006), Meadow (1994) presents detailed instructions for Christians to engage in this practice as taught in the traditional Theravāda approach. In addition, in a book on Christian Insight Meditation, Meadow, Culligan, and Chowning (1994/2007: 210) also commend insight meditation for Christian practitioners wishing to follow the path of St. John, in the belief that “John’s teaching on the ‘substance of the soul’ well mirrors [the] Buddhist understanding” of not self. From the viewpoint of the final goal, Meadow, Culligan, and Chowning (1994/2007: 217) propose the following:

How similar these teachings are! We have in the final end the substance of the soul knowing God, or the knowing consciousness fixed on Nibbana. Our capacity for experiencing is full of only the Ultimate, in which all else is found. Any other ‘thing’ we called ‘me’ or ‘I’ is unimportant.

Based on this premise, Meadow, Culligan, and Chowning (1994/2007: 165) commend the practice of insight meditation as taught by Mahāsi Sayādaw to Christians wishing to progress to the loving union with God as described in the writings of St. John of the Cross:

The specific quality of Christian insight meditation as contemplative prayer is its focus on purifying the heart and emptying out self to dispose us to receive God’s gift of contemplation. Insight practice disposes us to stay empty before God’s action. It helps prepare us for the gift of contemplation by actively purifying sense and spirit through faith, hope, and love.

This proposal has received support by Steele (2000: 219), based on pointing out that taking this position requires assuming that “the endpoint of Theravadan Buddhist vipassana meditation (nibbana) and the endpoint or ultimate goal of John’s spirituality (union with God, spiritual marriage) be the same.”

Pursuing this requirement, Steele (2000: 225) argues that, similar to Buddhist doctrine, for “John of the Cross, reality is also divided into the conditioned (creation) and unconditioned (God). The goal of the spiritual life, the ultimate goal of life, is to attain the experience of the unconditioned (spiritual marriage, union).” Moreover, from a Buddhist perspective, “all that is, changes, moves, except nibbana. For John, this is also the case. All things are seen to move and change, except God” (Steele 2000: 226).

Nirvana and God

Before further exploring the suggestion of similarity in relation to conditionality and absence of change, a helpful background for understanding the attraction of perennialism can be established with the help of observations by Wildman (2006: 84) in relation to potential problems when comparing religious traditions:

Human beings have highly developed pattern recognition skills, which are especially useful for recognizing the significance of facial expression. These skills … also lead us to expect patterns where none exist, or at least none at the level we seek. This is one of the great liabilities that human beings bring to observation and inquiry, and psychologists have documented its effects in great detail. It is equally a liability in comparison, where untrained human beings are too ready to find similarities on the basis of a quick glance. This maximizes vulnerability to error due to overconfidence, and marginalizes the careful observation and analysis of theoretical frameworks that we need to save comparative conclusions from becoming victims of casual hubris borne of over-active pattern recognition skills.

Turning to the case of the suggested similarity between Nirvana and God as both standing for the unconditioned, this proposal can be examined in light of a central aspect of early Buddhist thought: dependent arising. This centrality emerges in a famous statement that “one who sees dependent arising sees the Dharma,” in the sense of seeing the teaching of the Buddha.

According to Jurewicz (2000), the formulation of dependent arising in early Buddhist thought stands in dialogue with a Vedic creation myth. The Buddhist adaptation of this myth involves a reversal in meaning, as the overall orientation of this adaptation is to bring about a cessation of the conditions described in the standard formulation of dependent arising (Anālayo 2020). Nirvana as the final goal is unconditioned in the sense of being the cessation of all conditions, which is the very opposite of creation.

In contrast, God in Christian thought does not stand for the cessation of conditionality. Although himself being uncaused, God is in turn the cause of all things. This emerges clearly in the formulation found in the gospel by St. John (1.3): “all things came into being through Him and nothing came into being that did not come into being through Him.” This amounts to a proposal of mono-causality rather than of the complete cessation of conditionality.

The same substantial difference then applies to the question of change, which from a Buddhist viewpoint can be considered as the other side of the coin of conditionality. Buddhist texts do not posit any kind of eternal creative principle and even make fun of the belief that a creator god could exist, attributing the very idea to a misunderstanding. This stands in direct contrast to the notion of God as the “eternal father” (padre eterno), an expression used by St. John of the Cross in his Ascent on Mount Carmel, or to the aspiration to achieve an “eternal life” (vida eterna), another expression used recurrently in the same work.

It seems that Feldmeier (2006: 91) could be right when proposing that “Nirvana and God are not the same realities.” From the viewpoint of teaching Theravāda insight meditation to Christians wishing to achieve union with God, uncertainty regarding the proposed similarity between the final goals poses a serious problem. Lacking certainty about the ultimate congruence of the two paths, it becomes ethically questionable to propose a form of practice that might lead practitioners to an experience quite different from what they aspire to.

The Origins of Insight Meditation

The type of insight meditation taught by Meadow, Culligan, and Chowning (1994/2007) to Christians has its origins in the colonial period in Myanmar (formerly Burma). In order to fortify lay Buddhists against the influences of foreign domination and to ensure the longevity of Buddhism, teachings from the Theravāda exegetical tradition were made accessible to laity on a wide scale (Braun 2013). These have their point of origin in a part of the Buddhist scriptures known as “Abhidharma,” which came into being a few centuries after the time of the Buddha. According to a prediction in Theravāda commentaries, the disappearance of Abhidharma teachings will herald the onset of the decline of Theravāda Buddhism. Such apprehensions led to an attempt to bolster tradition against the disintegrating influences of colonialism, with a focus first of all on the preservation of Abhidharma teachings.

In this context, insight meditation was taught alongside Abhidharma teachings, mainly for the purpose of leading to a direct experience of central tenets of Abhidharma thought. In this way, from a historical perspective insight meditation as taught by Mahāsi Sayādaw emerged as a byproduct of an attempt to fortify and strengthen the worldview of the Theravāda exegetical tradition. Now, as noted by Steele (2000: 218) in relation to the practices taught by Meadow, Culligan, and Chowning (1994/2007),

instruction in Christian Insight meditation is functionally training in Theravadan Buddhist vipassana meditation. As such, the practice is organically rooted in the perceptual or cognitive set of Theravadan vipassana practice. In that sense it cannot be neutral.

A key element in this perceptual and cognitive set of Theravāda insight meditation is the doctrine of momentariness, according to which everything exists only for a fraction of a moment. As soon as something has arisen, it will immediately cease.

Insight meditation in the tradition of Mahāsi Sayādaw aims at facilitating a direct experience of such momentariness by encouraging a fragmentation of experience, breaking it down into its various components. Slow-motion walking can help to separate the apparent continuity of walking into discrete parts. Labeling of anything experienced can foster a realization of the immediate disappearance of whatever has just been noticed.

Labelling and slow-motion walking are precisely the practices recommended to Christians by Meadow, Culligan, and Chowning (1994/2007: 45–53). Yet, such meditative strategies may not be the best choice for someone wishing to achieve union with an eternal creator God. This is not to ignore a considerable degree of overlap between mindfulness practice as such and Christian mysticism (Campayo 2014), wherefore the cultivation of mindfulness could indeed be of substantial support for someone wishing to follow in the footsteps of St. John of the Cross. However, for this purpose, the type of mindfulness taught in contemporary Mindfulness-Based Practices would probably be a more suitable candidate than Theravāda insight meditation, simply because the latter risks leading Christian practitioners to realizations that do not align with the goal of their aspirations.

Conclusion

The in itself intriguing and promising avenue of different spiritual traditions learning from each other needs to be set within the context of a clear awareness of what are potentially substantial differences in orientation that inevitably manifest in the ways contemplative practices are formulated and undertaken. In relation to the case study taken up here, for the purpose of progress to loving union with the eternal creator God recognized in Christianity, the wholesale adoption of Theravāda insight meditation does not appear to be a straightforward choice, as it risks leading practitioners away from the goal advocated by St. John of the Cross in his writings. Progress to this goal could better be served by adopting a general type of mindfulness practice and the cultivation of mental tranquillity through mettā meditation, relying on the skills offered in Theravāda practice manuals for the attainment of absorption. Such attainment, considered in Buddhist cosmology to lead indeed to union with the ancient Indian creator god Brahmā, has much in common with the path and goal of Carmelite prayer and for this reason could indeed offer an enriching mode of practice for those who wish to embark on the path of Christian mysticism.

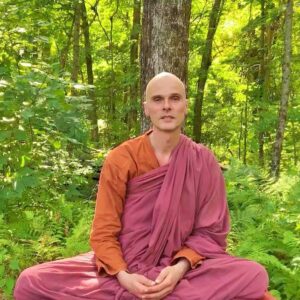

Bhikkhu Anālayo is a scholar-monk and the author of numerous books on meditation and early Buddhism. As the resident monk at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies, he regularly teaches online study and practice courses and undertakes research into meditation-related themes.

You can explore Bhikkhu Anālayo’s freely offered teachings.

You can download a PDF version of this article.