This article is based on teachings given at BCBS in January, 2008 by Paul Simons & Gregory Bivens in a course called Working with Addiction: Spiritual Self-Schema Therapy.

It might seem strange to talk about “spiritual self schema” as something to aspire to in a Buddhist context. In the psychological language of Self-Schema Therapy, it describes an alternative to the “addict self,” the type of mistaken identification with one’s negative thoughts and feelings that perpetuates a cycle of addiction to dangerous substances and behaviors.

Spiritual Self-Schema (3-S) therapy, developed at Yale University, is designed for those trapped in cycles of addiction and for the mental health professionals who work with them. It combines Western cognitive-behavioral therapies with Buddhist psychology to provide a very practical, day-to-day set of tools for empowering people to free themselves from habits that harm themselves and those around them.

For those of us not trapped in addictions to physically dangerous substances and behaviors, some of this might seem strange and unrelated to our experience. On the other hand, while perhaps not as physically dangerous, some of our addictions to unwholesome mind states can seem just as strong, making the raw experiences discussed here seem oddly familiar.

The therapy process draws on all aspects of Buddhist psychology, notably mindfulness as a tool for interrupting dangerous thought patterns leading to addictive behaviors. This article focuses on how the moral discipline (sīla) sections of the noble eightfold path—right speech, right action and right livelihood—and its relationship to karma (in this case, cycles of addiction) are brought into the process of mental health professionals working with clients.

Non-harming as the first step

The second section of the intervention begins with the training in sīla, a word meaning integrity or morality. Morality here in the United States is sometimes confused with sexual morality, as if morality is totally encompassed by sexual relations; but this is not the case.

Since morality can be such a loaded word in our culture, we might better think of sīla as “training in integrity.” The flavor of this training is suggested by the verse from the Dhammapada, “As I am, so are others, and as others are, so am I. Having thus identified self and others, harm no one and give no harm.”

The three sections of the Buddhist eight-fold path dealing with integrity are right speech, right action and right livelihood. In the 3-S therapy, we begin by teasing out from the client some addict speech, addict action and some addict livelihood. The therapeutic goals of this are to look at these and see that they are incompatible with getting on a spiritual path.

We are going to reinforce the whole concept of integrity as “no harm to self and others.” Then in the experiential component we are going to replace some really negative addict-self scripts with some scripts of loving kindness about ourselves. It is not easy to do.

Discussion centers around the whole idea of morality being the foundation of a spiritual path. In all traditions, including Buddhism, basic morality—how I treat myself, how I treat others—is key to being able to move forward in a positive way on any path. We can then show how the addict self is a habit pattern of the mind incompatible with the spiritual path. The addict self is rather ambivalent about harming oneself and harming others.

You want to ask the client—and this is a great piece of the session—”Let’s talk a little bit about addict speech, what does the addict self say when the addict self is talking?” And you get some really wonderful expositions about types of things that the addict self actually says. Lying and manipulating are only the first iteration; gossiping, swearing, boasting about one’s capabilities of doing amazing amounts of crack and things like that. Then moving on to addict actions, we hear of drug use, of course, but also of sharing drug paraphernalia, having unsafe sex—these relate directly to the HIV, Hepatitis-C piece of the intervention. For addict livelihood, they are never really sure what to say. How does the addict make his money? What does the addict do to keep drugs in her system?

A better way to feel good

From there, the big issue is, why change? What’s in it for me? This is where it’s nice to be able to offer pieces of Buddhism as an ethical psychology. People are so used to morality being presented as being coerced and demanding, where one is good to others because that’s what God told you to do. Buddhism doesn’t really play that game. One of the things I like about the Buddha is he’s asked over and over again, tell us about Brahma. Can you tell us about God? And the Buddha says that’s really not what he’s teaching here. “I teach only about suffering and the end of suffering.” Of course many of his Brahmin listeners cannot imagine a path to perfection that did not involve God, but this is one of the things that makes the Buddhist perspective unique.

Buddhist ethics says that once you understand how the mind works, “doing the right thing” has a lot to do with feeling good.

In the 3-S approach we are not going to present “do no harm” as a moral imperative from any other source, because undoubtedly our clients have been hearing that since Sunday school. If anything, we are drawn more in the direction of the Christian teaching, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” We appeal rather to the client’s existing desire for self-gratification. And Buddhist ethics says that once you understand how the mind works, “doing the right thing” has a lot to do with feeling good, though not in the conventional sense of mere pleasure. Interestingly, it is the opposite of what we’re told in the West, where “doing the right thing” takes time, money, effort and self-denial.

There are two aspects of this to cover. The first is the Buddha’s understanding of the inherently harmful nature of hatred. Just as acid first burns the container in which it is held, before it can ever be used to harm another, so also hatred has a corrosive effect on its bearer. It harms us even before it harms others, and in many cases hatred might well do us a great deal of harm and never touch those to whom it is directed. As an example of this, I took a trip recently and the airline lost every last piece of my baggage. It was a teaching trip, and I lost all the handouts I was relying upon. I spent the entire night in my hotel room, prior to presenting 3-S therapy, writing nasty letters to the airline in my head. I was livid. How dare they? Then I thought, wait a minute, it’s not about me. They don’t even care if they’ve lost my bags. Who lost the sleep that night, the chairman of the airline, or me? I did. I was poisoned by it. Those of you in 12-step programs have heard the line, “What is the nature of resentment?”—It’s where I take poison and wait for you to die, right? It is the same basic concept. You cannot do evil without poisoning yourself first. You always harm yourself first before you harm others.

Karma also means the freedom to let go

The second aspect of the Buddhist teaching on integrity is that you are the heir of your actions. Nobody on earth should understand more clearly than drug users and alcoholics the consequential way that our universe works. I commit action A, consequence B arises. I could have that happen over and over and over in my life when I was using heroin, but I never drew the line between action A and consequence B; it was always through a series of missteps and miscommunications that I was picked up by the police. It had nothing to do with me, right? I always thought that one of the best headstones for an alcoholic or an addict would be “It’s all your fault.” What is that about?

The whole point is that the universe operates on certain fundamental rules, whether we want to accept them or not. The law of karma is: Wholesome actions result in positive consequences, unwholesome actions result in negative consequences. When you assist clients in drawing these lines between action A and consequence B, you begin to see clouds lifted from foreheads. They think, “Wow, I never realized that when I got stopped in the car it had something to do with them watching me cop heroin.”

So, draw the lines for clients. The good news about Buddhism—making friends with this whole concept of not-self—is this: At every moment I’m presented with an infinite amount of potential in terms of my choices. I can change at any time, because I don’t need to carry around the baggage of my past. I want you to think about it in the context of today; you are a very different person than the person who walked in those doors at nine o’clock this morning. You’ve had different experiences, you may have meditated for the first time, had different thoughts; you’re a very different person. At the level of physiology, every six years, every molecule in our bodies is changed out and we become literally a different person. The same can be true psychologically. You don’t need to carry around the baggage of the past.

I tell them the purest, cleanest shot of dope you will ever take is doing a kind deed for someone else.

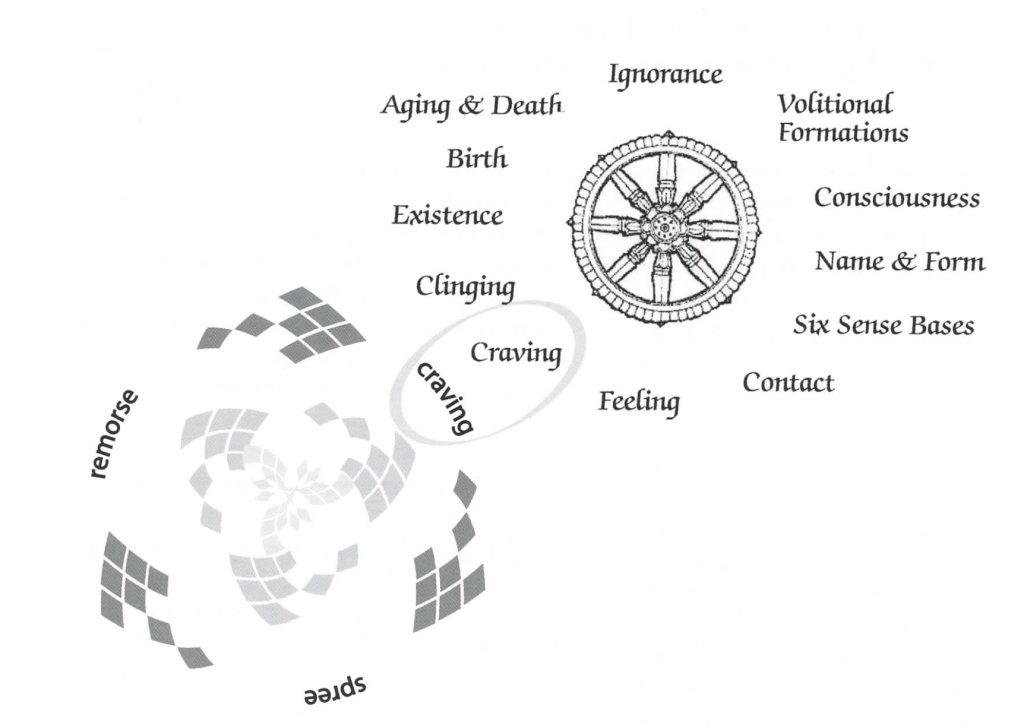

Further, and I think this is key: There is an escape from the trap. One of the most brilliant expositions about alcoholism and drug addition that I’ve read comes to us, through the 12-step program, from the big book about Alcoholics Anonymous. It’s written by a doctor who doesn’t believe in the spiritual stuff, but is grounded in the empirical evidence of his work with alcoholics and addicts. He identifies a continuing cycle of spree and remorse by which the addict is caught, and he says that what always generates the energy for this cycle is not the spree but the remorse. If I can let go of that remorse, if I can let go of that past—make amends for it certainly—then I move into a place where I am changing and options open up to me over time. At any moment there is this link between sīla—right speech, action and livelihood—and karma, on the positive side.

The spiritual self does take responsibility for its actions, does recognize change, and is willing to learn from the past rather than use it as a weapon, as a lot of people do. I like the Zen story of the master and student preparing to cross a river when a woman comes along and asks for help crossing over. The master picks her up, places her on his back, carries her across the river and sets her down on the riverside. The student and master then walk on for three days, until the student suddenly turns to the master, livid, and says “I cannot believe it! You are a monk, yet you touched a woman. Her garment was all up around her legs; it was a disgusting display, I am horrified.” The master replies, “You must be a very powerful man, because I just carried her across the river, but you’ve carried her all the way from there to here.”

Learning to let go is one of the hardest parts about penance, alternately making amends and then beating ourselves up for it. Being able to let go of it, and recognizing that is not me, that is not mine, that is not a permanent piece of who I am—it’s tough. If you can’t do that, then you are again on that larger cycle of spree and remorse. But whether by twelve steps or by the eightfold path, you can put that behind you.

Better than drugs: compassion

At last we talk about compassion. All beings suffer, all beings experience anxiety and stress and all beings have a desire to be happy. Let’s return to the first iteration of Buddhist ethics, “How does it feel?” What are the physical sensations of hatred, of ill-will, of cruelty? The whole point of doing good things for people is because it makes me feel good.

When I work with clients, using a language they understand, I tell them the purest, cleanest shot of dope you will ever take is doing a kind deed for someone else, while the worst withdrawal you’ve ever had is by being cruel or unkind. It can be a revelation for people to comprehend that doing good can feel good, since it goes against so much of what we are normally taught. I was raised a Mormon, and what was presented to me in Sunday school is that doing good things is really difficult. When you tell clients it can actually feel good, they say, “Oh, I never thought about that before.” But it’s true. The Buddha explained that the reason why it physically feels good to do good is because we’re feeling the karma of our former actions coming to fruition.

Experientially, this results in a lot of interest in loving-kindness (mettā). It is something consistent through all the world’s traditions, and it is where the mind resides on the spiritual path. Some people get the sense that mettā is like praying for someone or sending them positive vibrations. But it is not really about changing the environment in any way, it is about changing what’s going on in your mind, as you encounter others and as you encounter yourself. By evoking a sense of empathy, and identification with all human beings, we are going to experience the immediate benefits of generating loving kindness.

Even if I wake up from auto-pilot and find myself on Dope Street, I still have a thousand options in front of me.

Healing from addiction also has a lot to do with learning to replace harmful addict scripts with more healthy scripts. Not all these scripts, we find, are just justifications to use drugs or alcohol. Some of the most deeply toxic ones are things like “I’m no good,” ” I wish I had that car,” “I wish I earned more money.” I’m sure none of you have ever had that kind of thought. It’s remarkable how we’ll accept hearing things from ourselves that we would never accept from others.

The key factor in all of this is awareness, the ongoing awareness of what’s happening in the mind-body over time. We train people to be aware of some of the feelings they’re having, some of the thoughts they’re having, and learn to see whether they are coming from that unwholesome addict-self. With that awareness, they can be encouraged to avert the mind from these unwholesome thoughts, leading to unwholesome behaviors, and to turn instead to more wholesome thoughts and to different behaviors. Even if I wake up from auto-pilot and find myself on Dope Street, I still have a thousand options in front of me. I can still choose. I know this to be true, and am helping other see that it is true also.

For more on 3-S therapy, see www.3-s.us.

About the Presenter

What is salient in my story is first that I was a heroin addict for about 20 years. In most people’s minds that conjures images of street life, sleeping behind dumpsters and the like. In my case, I was, until the very end, pretty successful.

I ran companies, supervised employees, directed HIV prevention services at a large metropolitan public health department and was a lobbyist at a state legislature—all the while sneaking around the corner to get high. I finally crashed spectacularly and found myself alone and living on the streets of Denver. My family intervened and I awoke one morning in a treatment center in Southern California.

While there I began looking into various forms of spirituality, and since the great, important things in our lives have a tendency to find us, I encountered, while visiting a Pure Land Buddhist temple in Anaheim, a group of Zen monastics who in the space of an afternoon taught me a very truncated version of the Dhamma.

It all clicked and I knew I’d found what I had been looking for, or perhaps what had been looking for me. Again, what is salient is the central concept of suffering and how its root is craving, clinging. For a heroin addict in withdrawal, craving takes on a powerful, unpleasant, and seemingly unending physical manifestation. For that individual Dhamma becomes second nature.

Since that time I have been drawn more to the Therevadan tradition, and as a result got a chance to work on the training in Spiritual Self Schema Therapy and then to train hundreds of therapists, in the U.S. and Canada, in its implementation.

I currently teach a number of workshops around the country for federal, state and local agencies and am also creating some new training material on spiritual practices as they relate to the clinical setting.