The knowledge of neuroscience has doubled in the last twenty years. It will probably double again in the next twenty years. I think that neuropsychology is, broadly, about where biology was a hundred years after the invention of the microscope: around 1725.

In contrast, Buddhism is a twenty-five-hundred-year-old tradition. You don’t need an EEG or MRI to sit and observe your own mind, to open your heart and practice with sincerity. I don’t think of neuropsychology as a replacement for traditional methods, but simply as a very useful way to understand why traditional methods work. This is helpful in our culture, since arguably the secular religion of the West is science. If you understand why something works in your own mind, that promotes conviction (saddhā, trust in the Buddha’s teachings). Understanding a little neuropsychology also helps you to emphasize or individualize those particular aspects of traditional practices that best suit your own brain; natural differences in the brain are a fundamental kind of diversity, and if teachers and meditation centers want to respond to the needs of their existing members and to reach out to new ones, they will have to take into account normal variations in the brain.

Breakthroughs in brain science create opportunities to develop new or refined methods of practice. As Buddhism spread through Tibet, China, and Japan, it learned from the cultures in those lands and developed new methods. Similarly, as Buddhism has come to the West and encountered what is arguably its dominant cultural force—science—it is beginning to draw on science for ways it, too, might be of use on the path of awakening. Not in any way to change the aims of practice—as the Buddha said, I teach one thing: suffering and its end—but to increase the skillful means to that end.

Immaterial experience leaves material, enduring traces behind. In the saying from the work of the psychologist, Donald Hebb: “Neurons that fire together, wire together.” This is a neurologically informed way to appreciate why your experience really matters, and how important it is to have a kind of mental hygiene, to really appreciate what we allow in our minds.

Perhaps your mind is running themes of threat, grievance, and loss. Or alternately, perhaps it is running heartfeltness, generosity, kindness to self and others, awakening. Whichever movie we’re running, those neurons are firing and wiring together. So learning how to use your mind to shape the wiring of your brain is a profound way to support yourself on the path of awakening.

The mind & brain co-arise co-dependently

There’s been a lot of research and clarification over the last several decades about how the brain makes the mind, and how the mind makes the brain, in a codependent, circular kind of way.

Let’s begin with some clarifications:

- By “mind” I mean the flow of information through the nervous system, most of which is forever unconscious. We privilege what’s in the field of awareness because that’s what we’re conscious of. But cultivating beneficial factors down in the basement of the brain, outside of conscious awareness, is actually more influential in the long run.

- Further, the brain is embedded in larger systems, including the nervous system as a whole, other bodily systems, and then biology, culture, and evolution. It is shaped by those systems, and also shaped by the mind itself. For simplicity I’ll just refer to the brain, but really we are talking about a vast network of interdependent causes. Much as the Buddha taught.

- There may well be transcendental factors required for the mind to exist, to operate: call those factors God, Buddhanature, the Ground, or by no name at all. Since by definition, we cannot prove the existence or non-existence of such transcendental factors either way, it is consistent with the tenets of science to acknowledge transcendental factors as a possibility. That said, and with a deep bow in their direction, we will stay within the frame of Western science.

- Within that framework, the brain is the necessary and proximally sufficient condition for the mind. (It’s only proximally sufficient because the brain is nested in a great network of causes, without which the brain could not exist.) This view, generally shared within Western science, is that every mental state is correlated with a necessary and proximally sufficient brain state.

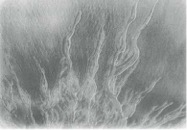

Mental activity is like a spring shower, leaving little traces of neural structure behind…

This integration of mind and brain has three important implications. First, as your brain changes, your mind changes. Second, as your mind changes, your brain changes. Many of those changes are fleeting, as your brain changes moment to moment to support the movement of information. But many are lasting, as neurons wire together: structure builds in the brain. Mental activity is like a spring shower, leaving little traces of neural structure behind. Over time, the little tracks in the hillside draw in more water down, deepening their course. A kind of circular self-organizing dynamic gradually develops, and then the mind tends to move more and more down that channel, and soon enough you’ve got a gully.

For example, if you are using neural circuits a lot, they actually become more sensitive to stimulation, for better or worse. Over time if a region is increasingly active, it gets more blood flow, more glucose, more oxygen and so forth. Existing synapses get stronger and new synapses form. Cortical layers actually get thicker as neural structures build; for example, the thickening in the part of the brain called the insula—which senses the internal state of your body—that is due to meditation, is on the order of a two-hundredth of an inch, which may not sound like much, but that’s lots and lots of new synapses.

Remarkably, synapses began forming in your brain before you were born, and your brain will keep changing up to the point of your last breath. Since neural activity continues in an increasingly disorganized way for a few minutes after the last breath, synapses may still be forming as the lights in the great mansion of the mind slowly go out.

Remarkably, synapses began forming in your brain before you were born, and your brain will keep changing up to the point of your last breath. Since neural activity continues in an increasingly disorganized way for a few minutes after the last breath, synapses may still be forming as the lights in the great mansion of the mind slowly go out.

The third implication is the practical one, and that’s where we ll focus: you can use your mind to change your brain to benefit your whole being— and every other being whose life you touch.

Your complex, dynamic, interdependent brain

Your brain has about a hundred billion neurons in it (see “Amazing brain facts,” below, for more basic facts about your brain). In principle, the number of possible states of the brain is the number of possible combinations of a hundred billion neurons either firing or not (“on or off’). That number is really big: ten to the millionth power, which is one followed by a million zeros. To put this in perspective, the number of particles in the known universe is about ten to the eightieth power—one followed by eighty zeros versus a million zeros. The brain—your brain, right now—is the most complex object known to science. It’s more complex than an exploding star, or climate change.

The brain functions through a mixture of specialization and lots and lots of teamwork. Parts of the brain do specialized things, like the speech centers in the left temporal and frontal lobes. On the other hand, if you map the communications pathways among the regions and specialized tissues of the brain, you see that it’s highly interconnected. It’s a little bit like tracking roadways from space or information on the Internet: a very dense network. So when people talk about specialization and function in just one place, like “The amygdala is the fear part of the brain,” or “The left hemisphere is bad and the right hemisphere is good,” it’s an inaccurate simplification.

Understanding the chaotic and sometimes frankly wacky flux of neural activity can allow you to take it less seriously.

Within the networks of the brain, there are lots of circular loops. To simplify, there is the “A” neuron connected to the “B” neuron, connected to the “C” neuron, connected to the “D” neuron, and then back to the “A” neuron. These possibilities of recursion, as a computer programmer would call it, give you the capacity—among other things—to become aware of awareness.

Neurons also share each other. To simplify again, let’s say you activate the “C” neuron in our A-B-C-D-A loop, and the “C” neuron is shared with another loop. So there you are, irritated because the faucet’s dripping in the middle of the night, and suddenly you think about the smell of your grandmother’s cookies. Why? For some reason, there was shared circuitry in the coalitions of synapses that momentarily formed. The discursive stream of consciousness is so complex that as a system it exhibits some chaotic qualities. Understanding the chaotic and sometimes frankly wacky flux of all that neural activity can allow you to take it less seriously.

Neurons often fire in harmony with each other, five to fifty times a second—maybe even eighty or a hundred times in some parts of the brain. They’re synchronizing with each other, and that’s what produces the rhythmic waves of electrical activity—”brainwaves”—that are picked up with EEGs. Types of brainwaves are grouped together based on how fast they are; for example, brainwaves that happen 30-80 times a second are called gamma waves. In one study, when experienced Tibetan practitioners meditated, there was a spreading and strengthening pattern of gamma wave activity in the brain: billions of neurons firing in harmony with each other, 30-80 times a second. Synchronizing microscopic neurons spread across broad regions of your brain is like everybody between Barre and Boston clapping in unison let’s say thirty times a second. Wow! And these effects of synchronization and integration are seen outside of formal meditation: in the same study, those Tibetan monks—who have done 30,000 to 50,000 hours of meditation in their lifetimes—have resting state gamma activity that’s greater than people who don’t have so much practice. This suggests that, as we practice more and more, there’s more integration and coherence in the brain—which corresponds to a growing stability and spaciousness, equanimity in other words, in the mind.

As we practice more and more, there’s more integration and coherence in the brain, growing stability and spaciousness—equanimity, in other words.

Brain and body benefits of meditation

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is a brain region that is ground zero for a lot of very important functions. For one, it’s the part of the brain that manages what’s called “effortful attention,” which is basically paying attention in a deliberate way. That sounds like meditation. The ACC is the part of the brain we use for mindfulness in all four postures, not just seated, but walking, lying, and standing. It’s also the main source of the focused attention we use for talking, and doing other activities that call for deliberate focus. Your cingulate cortex tends to get thicker to the degree you meditate.

For many people, it’s easy to feel when they feel, or think when they think, but to bring mental clarity into being upset, or to warm up cold cognition with heartfelt emotion, is hard. The capacity to do that is centered in the anterior cingulate cortex. So, for example, doing things like compassion meditation, particularly mingling thoughts and feelings of compassion together, stimulates the ACC and therefore strengthens it; you’re firing those neurons and therefore you’re wiring those neurons.

Another region that gets thicker with meditation is called the insula. If you strengthen a part of the brain through meditation, you get to reap those rewards for other uses. For example, the insula is crucial for one the three main aspects of empathy: visceral resonance with the feelings of another person (the other two aspects are simulating inside yourself the actions [“mirror systems”] and the thoughts/wishes/psychodynamics [“theory of mind”] of others). To the extent that we’re in touch with own inner being, including our gut feelings—and this degree of in-touchness correlates with the activity of the insula—we become more able to be empathic with others.

True compassion, true loving kindness, requires empathy. I’ve known people who are sort of generically compassionate, and generically kind, but aren’t actually moved by the inner state of the other person. That’s not the real deal. So it’s foundational to strengthen your empathy. I can tell you from twenty-seven years of marriage, empathy’s a good thing! (And there are of course lots of important places for empathy outside of marriage.) Also, if you understand how to be empathic yourself, you understand better how to ask for it from others.

Meditation is probably the most researched mental activity in terms of neural impact. We know, for example, that meditators have less cortical thinning with aging. As I see more gray hairs on my head every year I appreciate the fact that one of the great ways to promote mental faculties well into old age is through contemplative practice. One exploratory study has shown a correlation of about a fifteen per cent reduction in Alzheimer’s symptoms if a person has a religious background (there was only one Buddhist in the sample, and any kind of religious activity counted, but the study is still suggestive). That reduction of fifteen percent is about as much as the best current medication can do for Alzheimer’s.

In another example, Richard Davidson did a very interesting study with people in a high tech company. He had some of them do daily meditation. After just six weeks, the people who meditated had stronger immune systems. They fought off a flu virus more effectively than people who hadn’t meditated.

So meditation benefits us through multiple pathways. Parasympathetic activation (“rest-and-digest”)—relaxation, in other words—is very supportive of immune system functioning, whereas sympathetic activation (“fight-or-flight”) suppresses immune function. Chronic stress exposes us to illness to a marked degree. Sleepy meditating is better than no meditation in terms of parasympathetic activation, or dampening sympathetic arousal (wakeful meditation is usually best of all). We can get attached to and even righteous about one specific method, whereas actually meditation has a lot of important general effects not specific to any particular method.

Equanimity can break the chain right between feeling tone and craving, like a jumbo scissors.

Another major Richard Davidson finding is that people become increasingly happy as they meditate—positive emotions become more prevalent, broadly defined. There’s a greater asymmetry of activation, left front to right frontal. To illustrate this with stroke patients, people with a stroke in the right frontal region tend to become kind of mellow. Maybe they can’t walk well, but they’re often relatively serene about it. But if they have a stroke in the left frontal region, they’re a lot more likely to be grouchy and grumpy.

Why is that? Because the left frontal region is involved in dampening, inhibiting negative emotional activity, whereas the right frontal region tends to promote negative emotional activity. In the wild, there’s a lot of survival value to negative emotional activity; right hemisphere activation—which tracks the spatial environment from which most threats originate in the wild—primes you for dealing with threats: in other words, primes you for aversion, for what are called avoidance behaviors, namely fight, flight, freeze, appease. Maybe sometimes those behaviors are useful; in our evolutionary history, they certainly promoted survival and passing on genes. But today, in different settings and with different aims (like spiritual practice), it’s great to have relatively strong left frontal activation.

Dependent Origination, brain, & equanimity

The feeling tone is a good example of where the Dharma maps well to neuropsychology. In the Dharma, there’s this notion of the chain of Dependent Origination. One part of that chain that contains great opportunities to reduce or eliminate suffering is the sequence of contact > feeling tone > craving > clinging > suffering.

Contact is the meeting of three things: an object, the sense organ that apprehends that particular kind of object, and the consciousness that goes with that particular sense organ. Following contact, the brain produces a feeling tone that is pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral to help you know what to do: approach the pleasant, avoid the unpleasant, and move on from the neutral. This mechanism is a very effective way to promote survival in the wild and the passing on of genes. Feeling tones are important in evolution and they are a central theme in the Dharma: for example, they are one of the Five Aggregates, and also one of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness.

Say the phone rings. Depending on whether you’re waiting for a call from a dear friend, or doing something really important and don’t want interruptions, you’ll get a different feeling tone: pleasant, unpleasant or neutral. In the brain, the amygdala and hippocampus register pleasant/unpleasant and then broadcast a signal widely.

In Dependent Origination, what follows feeling tone is craving. We crave the pleasant, and the ending of the unpleasant. Either way, it’s a kind of craving. After craving comes clinging, a sort of a more congealed, substantiated, enacted, “you’re in it” form of craving. And then, what follows clinging? Suffering.

Equanimity can break the chain right between feeling tone and craving, like a big, jumbo scissors. You let the feeling tone be. It gets into the “mud room” of your mind—that outer room where the muddy boots and wet jackets get left—but it doesn’t enter the central “living room” of your mind. Equanimity increasingly allows us to just be present with the pleasant, the unpleasant and the neutral, alike, without getting reactivated around them.

Equanimity is a very deep matter in Buddhism. It is one of the Seven Factors Of Awakening, and one of the hallmark characteristics of jhānas (states of concentration). Notice, for example, the difference between calm and equanimity. Calm is when you don’t have reactions. You’re chilled out. But with equanimity, you’re not reacting to your reactions; they stay in the mud room. It’s as if the reactions are surrounded with a lot of spaciousness. You prefer the pleasant to continue and the unpleasant to end—that’s OK. But you don’t even react to not getting that preference. You just surround it with space, and that’s where freedom is. I think that’s how people like the Dalai Lama can be sorrowful about what’s happening in Tibet, and yet simultaneously have enormous equanimity around it.

Calm is based on conditions, and thus not that reliable. But equanimity is based on insight, wisdom, and is thus much more dependable. For example, disenchantment is a key factor of equanimity. We start to realize, “Won’t get fooled again.” Ice cream tastes like ice cream, orgasms are orgasms, being angry is being angry. Winning an argument, being right and showing them the error of their ways is just that. After a while you go, “so what?” Wisdom allows you to let go of the lesser pleasure, chasing the pleasant or resisting the unpleasant, for the greater pleasure of equanimity

Abiding increasingly in that fertile, generative space in which neural assemblies take form is a central process along the path of awakening.

What happens in the brain when people become equanimous? In a sense, equanimity is unnatural, since we evolved to get really good a reacting to the feeling tone. Our ancestors that were all blissed out, and not driven to find food and mates, and not driven to avoid predators and other hazards… CHOMP, did not pass on their genes. The ancestors who lived were extremely easy to activate into states of “greed” and “hatred;” realizing this helps bring self-compassion to a path of practice that involves, in part, moving upstream against evolutionary currents. And it is important to remember that when we are not activated, our natural resting state is characterized by the Five C’s: Conscious, Calm, Contented, Caring, and Creative. It’s just that we are very vulnerable to signals of opportunity and threat—and especially to signals of threat, since in evolution it is more important to dodge sticks than to get carrots: if you miss out on a carrot today you’ll probably get another chance at them tomorrow, but if you fail to duck the stick today—POW—you won ‘t have any chance for carrots tomorrow. I think this is the evolutionary reason for the Buddha’s emphasis on dealing with aversion, since aversion to threats is so central to human existence.

In your brain, equanimity entails insights and intentions centered in the prefrontal cortex as well as prefrontal buffering of the feeling tone signals pulsed by the amygdala. It also entails the stable spaciousness of mind characterized by increased gamma wave activity of the brain. These neural developments are the fruits of sustained practice.

Seeing the origins of mental activity

One of the possibilities of meditation, or practice broadly, is to get us closer to the bare processing of “this moment, this moment, this moment.” The brain takes the noisy, fertile chaos of billions of neurons networked together in intricate and transient circuits, and then it forms assemblies which may last a few tenths of a second, or a few seconds at most. When you observe your mind you can see the outer signs of this neural activity by watching your thoughts merge into solidity and then crumble and disperse.

Just before a new neural assembly forms, there’s a space of fertile emptiness, where structure hasn’t yet congealed. Once a representation becomes fully established—an image, an emotion, a view, a thought—it is no longer free. You can have freedom around it, but whatever it is, that representation is set until it disperses.

So abiding increasingly in that fertile, generative space, in which neural assemblies take form, is a central process along the path of awakening. I think the people who are really far along in the practice are increasingly abiding in that territory. Thought is occurring, but they’re living more in that space of fertile freedom.

Self is like a unicorn

Components and functions of the apparent self—Me! My Precious! I want! How’m I doin’?—are widely distributed in the brain. Take just three kinds of self-related activities. One is recognizing yourself, distinct from other people, or noticing an “x” on your forehead someone put there without you realizing it. Only a few animals can do that, including humans, other “great apes” such as monkeys and gorillas, whales and dolphins, and elephants. Another aspect is personal history, your memories. The third aspect is making decisions; I want chocolate, not vanilla, for example. Studies have shown that those self-related activities are spread out throughout your brain. There’s no homunculus looking out from your eyes. Self in the brain is just like the Buddha says in the Dharma: compounded (made of many parts), variable and transient, and interdependently arising. It has no inherent, underlying self-arising on its own; therefore it’s empty of absolute existence.

Self does give rise to desire, but much of the time, it is desire that gives rise to self.

Much of the time there’s not much selfing present; there is presence and mental activity without much activation of “I” or “mine.” You shift your body in your seat because it’s gotten tight somewhere: probably there’s not a lot of self present. But suddenly someone says something to you, or you notice, hum, their chair is crowding into mine: Hey, don’t you respect my space?! Then the self really activates. There is a process of varying self-related activities; self is not a noun but a verb: there is selfing. Selfing developed in evolution to help us survive, and so it shows up particularly under three conditions: pursuing opportunities (often associated with “greed”), avoiding threats (often associated with “hatred”), and interactions with others (since we evolved to be the most social animal of all).

Aspects of self arise as impermanent but existent patterns of mental and therefore neural activity. These patterns exist in the sense that the patterns which correspond to a thought of a butterfly or the knowledge that 2+2=4 exist. Patterns exist, but they’re impermanent and dependently arisen: they’re empty. Mental/neural patterns related to self are just more patterns in the mind and brain, not categorically different from other mental/neural patterns. The problem is that we privilege those particular patterns above all others. They are the ones we most identify with, and the trickiest ones to disidentify with as we proceed along the path of practice. The mental/neural activity of selfing is designed by evolution to continually claim ownership of experiences, claim agency of actions, and claim identification with both internal states and external objects (like political groups or sports teams we like): it’s very powerful! Watch your mind: a strong reaction will arise, let’s say, and for the first second or two there is not much self entwined with it, but quickly self jumps on the bandwagon and then claims the reaction as its own. Self does give rise to desire, but much of the time, it is desire that gives rise to self.

But actually, much of the time self is truly superfluous to functioning well in the world, and feeling good inside. Without much if any selfing present, there can be executive functions at work, such as organizing and planning or the will. There can be wholesome desire, chanda, present—which is distinct from taṅhā, thirst or craving, which the Buddha said caused suffering. Walk across the room: does there need to be self present? Lift the cup to your lips: is self needed?

The patterns of selfing in the mind and brain are real; they exist in the way that memory or an emotion exists. Their existence is transient and empty, to be sure, and thus not worth clinging to. But even more to the point: does what they point to, what they represent, actually exist? In other words, is there actually a coherent, unified, stable, enduring being somewhere, somehow, in the brain? Actually, no such being exists. Whatever of self there is in the brain, it is compounded and distributed, not coherent and unified; it is variable and transient, not stable and enduring. In other words, the conventional notion of self is a mythical creature. Representations of a horse in the mind/brain are real representations of a real thing. But representations of the self in the brain are like representations of a unicorn: real representations of an unreal thing. In sum, when you appreciate that the representations of self in the brain are empty, that what they represent does not exist, you start taking your own “self” much less seriously.

Conclusion

The reality is that the more we study how the mind and brain intertwine, the more we find how well it maps with Dharma. The Buddha clearly understood this cycle of using the mind to change the brain, which then changes the future mind. If this is done well, it reduces suffering. He showed us ways to examine our experience, see how this works, and use that intuitive, direct understanding to free ourselves from suffering—completely free ourselves, in this very life, potentially. Just about everything we have found in neuropsychology supports the idea that he was right. This should give us a lot more conviction in our practice, along with a continuing source of practical tools to make it a reality.

Amazing brain facts

Your brain weighs about three pounds, with the consistency of soft tofu. It is made of about 1.1 trillion cells. About a hundred billion of these cells are neurons; the others are the support structure of the brain, the white matter, the glial cells, predominantly, that help build myelination around the long axonal fibers of the neurons, which accelerate neurotransmission.

Each of those neurons on average has about five thousand connections with other neurons. That creates about five hundred trillion connections, called synapses. These are tiny little junctions between neuron “A” and neuron “B” where they communicate. In most neurons, each time a neuron fires, neurochemicals move across the synapse (a small fraction of your neurons make direct, electrical connections).

Each neuron is always either firing, or not. Each firing is a signal, like “green light/red light;” it tells the downstream neuron to fire or not. So each neuronal firing is like a bit of information in a computer, a zero or a one. Most of the neurons in your brain are firing five to fifty times a second. They are very, very busy.

As a result, this little organ, two percent of body weight, uses twenty to twenty-five percent of the body’s metabolic supplies. Even in the deepest sleep, even in a coma, the brain is busy. It’s like a refrigerator; it’s always on. The brain keeps going so that if you’re suddenly attacked in the wild or you’ve got to deal with something in your cave, kaboom, you’re ready to go.

We can recognize maybe four thoughts per second, if we’re pretty aware. If we get really quiet, we might be able to see eight to ten, at the most. Working memory circuits, which are a key neural substrate of conscious awareness, seem to update about six times a second. So that’s roughly how tight the granularity is of discrete thoughts. That is really slow, as far as the brain’s concerned. So what we think of as thought—this slow, congealed, turgid stuff—is just the tip of the iceberg of mental activity.

Rick Hanson, PhD, began meditating in 1974. A psychologist, writer and teacher, he co-founded the Heartwood Institute for Neuroscience and Contemplative Wisdom. This article is based on a course he taught at BCBS in April 2009.