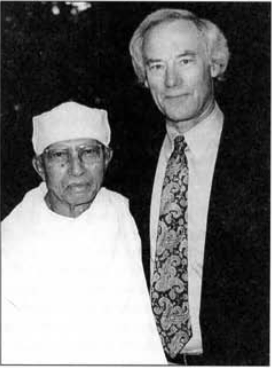

The following remarks continue the excerpt of a daylong workshop given by Jack Engler at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies on November l, 1997. Jack is on the study center board of directors, teaches at Harvard Medical School and practices psychotherapy in Cambridge.

I was fortunate in having a teacher who talked about awakening as though it were the most natural thing in the world. Munindra-ji assumed practice would lead to enlightenment. He had no illusions about what it would take: “Simplest thing in the world—most difficult thing in the world!” he would say. Still, it was part of his everyday thinking and teaching. How could you talk about Buddha-dharma and not talk about those moments in which you experienced the path and finally discovered who you were? He never told me not to “strive;” he assumed practice would unfold in this direction and encouraged me to devote myself to it.

It is harder for us to make the same assumption. We live in a culture with a very different view of human nature and human purpose. Our personal goals are often at odds with the goal of awakening. The western psyche seems to be structured differently, too. Our emphasis on autonomy and individuation at the expense of mutuality and interdependence, our drive toward individual achievement and our nuclear social institutions, leave us more prone to insecurity, loneliness and self-doubt, with more of a need to defend ego than still its agitation and grasping. The Dalai Lama, for example, has talked about his astonishment at the degree of self-criticism and self-hatred he found among Western students.

Our personal goals are often at odds with the goal of awakening.

These may be some of the reasons why we seem to have gotten away from the aspiration to enlightenment over the years. We don’t talk about it as much, even in teaching. We don’t make it the core intention in our practice, though I suspect it remains a secret aspiration in our heart. But why so secret? Why is it not acknowledged and talked about? How can we realize what we don’t consciously intend? How can we support each others’ efforts if we aren’t clear what our effort is about?

I’ve wondered about this. Is it that the aspiration is so daunting? Does it seem so impossible of fulfillment? Are we afraid of tempting fate or the gods to say this is what I want, this is what is most important to me? Perhaps in our culture, which has no conception of awakening and offers little support for it, the aspiration feels too much of a personal goal, and therefore too compromised by a sense of personal aggrandizement, or by the shame or guilt we can feel in acknowledging what we most deeply want. We are being too bold. We will be brought down, like Icarus who tried to fly too close to the sun. Perhaps we are afraid of provoking the envy and resentment of others, or their scorn and criticism: “Who are you to think you can……… ?! That’s just another form of attachment and striving!” Yes, of course, it can be.

But we can use these notions defensively to protect ourselves. They’re ready-to-hand rationalizations in spiritual guise. What’s there to protect ourselves from when it comes to our freedom? Lots. Anxiety and self-doubt; fear of not succeeding, of not getting what we want; of failing to live up to our ambitions and ideals. Fear of looking deeply into ourselves. Afraid we might not have “the right stuff.” It is always hard to own our own aspirations. The more noble and ambitious they are, the more dangerous they can feel, eliciting secret shame or guilt in ourselves or the fear of envy or ridicule from others.

Aspiring to awakening can awaken the deepest fear of all: discovering we do not exist in the way we think we do. The fact that we need to grasp at all and go on grasping is continual evidence that in the depths of our being we know that the self does not inherently exist. The fact that we talk incessantly to ourselves about ourselves in a never-ending internal monologue betrays our anxiety about the emptiness we might fall into if we stopped. “Without any true knowledge of the nature of our mind….the thought that we might ever become ego-less terrifies us,” says Sogyal Rinpoche. This “secret, unnerving knowledge” is unwelcome and unwanted. It makes us chronically restless and insecure. So we talk ourselves out of it. “I can’t do it.” “I don’t deserve it.” “I’m tempting fate.” “Others won’t understand.” “I’ll end up alone.”

Any process with the potential for real change evokes this kind of ambivalence. “Every patient,” says Robert Langs, “enters therapy with a mind divided.” But the mind is ratcheted up enormously in spiritual practice because ego projects awakening as something outside ourselves, and therefore perceives it (rightly!) as the ultimate threat to itself. As a source of suffering, “ignorance” (avijjā) in Buddhist teaching doesn’t simply mean not knowing the facts: not knowing the truth of anattā, for instance. Ignorance means “ignoring”: a dynamically charged ignorance; a not-wanting-to-know, a resistance to knowing, an allowing ourselves to know only so much. “The resourcefulness of ego is almost infinite,” says Sogyal Rinpoche, “and at every stage it can sabotage and pervert our desire to be free of it. The truth is simple and the teachings are extremely clear, but… as soon as they begin to touch and move us, the ego tries to complicate them because it is fundamentally threatened.”

By minimizing the importance of awakening we make our own self-doubts and insecurities easier to live with.

Anticipate the mind’s ambivalence and resistance to awakening, and then we will not be dismayed or deterred. Left to itself, the mind will always hedge its bets. “Your mind has a mind of its own,” my first vipassanā [insight meditation] teacher, Sujata, once wrote—”Where do you fit in?” That part of us would prefer not-to-know and will settle for relief instead—any relief if we feel badly enough—anything that will ease the pain and discomfort without requiring deeper inquiry into its source. Rather off-hand one day, Sujata said, “Let’s face it—we’re all pigeons for a little bit of sukha (pleasurable feeling).” I resented his crudeness at the time, but in part because he pointed to something I did not want to recognize.

Have you ever noticed how much more problematic happiness or joy are than unhappiness and misery? Happiness actually frightens us, doesn’t it? “It won’t last,” we tell ourselves. “I’ll crash, and then I’ll feel worse than before. At least when I’m miserable, I have nothing to lose. It sucks, but it’s familiar, and I don’t have to live with the anxiety of keeping this high wire act going. I don’t deserve to be happy anyway. I’ll pay for it one way or the other—God or fate or my karma will see to that. If they don’t, my superego will.”

A poet-professor of mine wrote many years ago in a meditation on the sacred in art, “It’s not the skeleton in our closet that we fear. It’s the god.” It is not ghosts which evoke our deepest anxieties. It is glimpses of freedom. Like the prisoner in Plato’s allegory of the cave, the shackles are off but the light outside is too bright; better the comfort and familiarity of the shadows on the wall of the cave. Sometimes even though the cell door is flung open, the prisoner chooses not to escape.

Instead of practicing for awakening as a real possibility, we hold enlightenment up as a remarkable and rare attainment, the highest ideal of the spiritual life. But enlightenment doesn’t work as an ideal. As an ideal for a few, it distances us and discourages us. At the same time, of course, this puts it comfortably out of reach where we can venerate it without feeling we have to do anything about it. And then we have to defend ourselves against our disappointment that it will never be ours. So we take the opposite position that it doesn’t really matter anyway—all that matters is being awake in the moment.

This may be true, but here it is used as a rationalization. By minimizing its importance, we make our own selfdoubts and insecurities easier to live with. Idealizing awakening and minimizing its importance are both defensive, and repeat what has already happened in the history of Buddhism. Awakening was a common occurrence in the beginning if we believe the suttas; over the centuries it came to be viewed as a rarer and rarer event as it took on more of a mystical aura, and most Buddhists eventually abandoned the aspiration for awakening in this lifetime. Is this coincidence?

Buddhaghosa [the 5th century commentator] called practice a visuddhimagga or “path of purification.” Wholehearted aspiration is often mixed up with pressures to unwittingly turn practice into another means of shoring up ego. From this initial alloy, the impurities are refined out in the fire of practice. But this requires intention, desire, the will-to-do—the mental factor Buddhist Abhidhamma calls “chanda.” Without this will or desire or intention to awaken, awakening will not happen. “I wanted to know the meaning of my life,” a student once said to Kapleau Roshi. “How did you ask your question?” Roshi replied. “Only when you are driven to cry from your guts, ‘I must, I will, find out!’ will your question be answered.” Aspiration can be confused with longing; longing is only a wish for what we believe we will never have. Aspiration is setting our face to the wind with conviction, purpose and intention. What we don’t intend we will never accomplish.

INSIGHT AND MOURNING

As long as we cling, we don’t awaken. So how do we let go of clinging? How do we let go of anything that we cherish and believe is essential to our happiness? That’s the crucial issue in practice, as it is in therapy and as it is in life.

We call our practice “insight” meditation, because in it we see the truth of anicca, dukkha, and anattā [impermanence, unsatisfactoriness and selflessness]. But insight alone is not transformative. Not in therapy. Not in meditation. Not in any process of transformation. How many times have you understood quite clearly what you should do, seen very clearly into some old pattern of behavior and why it doesn’t work, and yet found yourself still repeating it? Coming to see that someone or something needs to be surrendered and surrendering it are two different processes. It is the hard, working-through of insight that makes the difference.

At its core, this always involves coming to terms with some loss. Because genuine insight always challenges us to give up something we’re clinging to: a long-held belief, a mistaken image of self, a misplaced hope, a habit or familiar way of doing things, the assumption that someone we love will always be there. True insight means seeing things as they really are (yathā-bhūta), not as we want them to be. Coming to this acceptance is the work of mourning.

Mourning—letting go of the way we want things to be—is much harder than coming to understand that we must let go. We seldom, if ever, just accept anything, especially anything that threatens our safety and security, what we feel we need to survive. Most of the time, when reality doesn’t accord with our wish or the way we think things should be, we only come to accept it gradually, haltingly, sometimes with despair, always with resistance. Without grieving what we are being forced to give up, we don’t let go. Grief-work is precisely about coming-to-acceptance of a new state of affairs in which something we have cherished is absent. Through the work of mourning, insight becomes truth; maladaptive clinging and desperate holding on are surrendered and we start to live again.

This is never more true than in dharma practice, since what we confront and have to surrender is our clinging-to-self (attavād-upādāna)—a belief about who we are and how we are—that we have cherished for so long and believed essential to our happiness. Experiencing the reality of anicca, dukkha and anattā in each and every moment is the ultimate threat to our ego and security. Coming to an acceptance of these truths, which run counter to everything we want to believe and evoke the archaic fear of not existing, is the work that leads to awakening. Not samādhi [concentration], not insight, but acceptance.

The two people I know who experienced awakening very shortly after beginning formal practice, one in six days and one in six weeks, were both women who had suffered great losses in their lives not long before, and who were themselves close to death. One had lost her husband and two of her three children and had been given only weeks to live by her doctors. The other had made three suicide attempts. It was not because their samādhi was good (though it was). Both had already experienced profound anicca, dukkha and anattā. Both were already grieving deeply. Neither was holding on to much any more. Mourning had prepared them, much as the shock of his father’s death and subsequent poverty prepared the Sixth Zen Patriarch’s mind to awaken without formal practice on hearing the Diamond Sutra.

Awakening happens when self-grasping stops. Any experience of anicca, dukkha or anattā that is direct enough and deep enough will stop it. From one point of view, the higher “stages of insight” in vipassanā are just a way to introduce us to a direct and deep enough experience of anicca, dukkha or anattā that our mind will stop grasping. But Buddhist literature is full of stories—like that of the Sixth Zen Patriarch—that tell of awakening without formal meditation practice in someone whose mind has reached a point of readiness, someone who is no longer holding on to much.

Some of us have to be dragged, kicking and screaming, before we let go, and so there tends to be more struggle in the process. For others, it’s not a lot of struggle. Their conditioning and preparation is different. Mourning is a dramatic word, but the basic process is the same. There’s no way around that. Whatever the path and however the practitioner comes to it, the path turns on the working through of loss, acceptance and surrender—at every moment, but especially in the process of awakening.

Insight brings you to the door; only your capacity to leave something long-cherished behind enables you to walk through.

So insight and mourning go hand in hand. We can’t give up what we don’t understand. We have to come to know something for what it is before we can let go of it. We try to short-circuit this process all the time: “All right, take me, I give up, I surrender.” But premature surrender never works, because it isn’t based on fully facing whatever needs to be faced and working it through. Letting-go is not something we can just decide to do and do it, not when it comes to our most deeply held and our most cherished beliefs and attachments.

This is a somewhat different way of thinking about practice and what leads to awakening, but how could it be otherwise? If we’re going to let go of the ways of being and acting that constrict us, our ways of holding on to ourselves, then that’s going to confront us with loss. And the only way we can deal with loss and finally let go is through some process of mourning.

THE “PROGRESS OF INSIGHT”

For centuries, the Theravada tradition has described seventeen “stages of insight.” Each one is technically termed a ñāna or “knowledge.” At each stage, one comes to progressively deeper “knowledge” through direct experience of anicca, dukkha and anattā. This happens through a sequence of experiences which unfold in a natural progression, once you understand what they are about.

The sequence begins at the point at which the five “hindrances” (nīvarana) are no longer active, leaving moment-to-moment concentration deep, unbroken, and non-distractible. This is called “access concentration” (upacāra-samādhi) because this level of concentration accesses the stages of insight which lead to awakening. They are essentially about a process of insight and mourning. Cognitively, what the meditator actually does is retrace, step by step in his or her own experience, the process whereby consciousness literally constructs the world and self moment by moment—it actually brings them into being.

It is remarkable that we can observe this. Normally we are only aware of the end-products of this process after they are fully formed—thoughts, concepts, perceptions, feelings, and sensations that make up our ordinary experience. At this stage in practice, however, consciousness can observe its own moment-to-moment working in bringing these elements of our ordinary experience into being. You come to see directly the fabricated, momentary and interdependent nature of the self and “reality” by actually experiencing the steps in their construction. “Meditation,” says Mircea Eliade in his great book on yoga, “reverses the way the world appears.”

Buddhaghosa describes what happens at the start of this process as “dispelling the illusion of compactness.” From the very first ñāna our reality is turned inside out—like passing through the looking glass—from our normal world of apparent substance and solidity to a rushing stream of momentary, discrete and discontinuous events. You discover first-hand, in your body-mind, the discreteness and temporality that is the fundamental order of things, whether subatomic particles, DNA, or consciousness. In this rushing stream, “I” am no longer an independent observer observing. Consciousness no longer appears continuous or localized as it normally does—the sensation of “me” being “here” observing events “there” drops away. There are thoughts, or movements in the mind that will emerge as thoughts, but no “I” thinking them—thoughts without a thinker; feelings and sensations, but no “I” feeling or sensing them. Instead consciousness is experienced as a radically temporal process, coming to be and passing away, rather than a unitary and ongoing state of awareness. All that is discernible are discrete moments of consciousness, themselves part of the stream of events, not outside them as a separate observer. There is no ontological core to consciousness or self to be found anywhere that is independent and enduring.

When we see our own existence slip through our fingers like water through a sieve, we don’t say “Whoopee! This is wonderful!”

Nor are there stable “objects” of observation, just the stimuli out of which “objects” (thoughts, sensations, feelings, perceptions) are being ongoingly constructed—a view now confirmed by neuroscience and contemporary cognitive research. In this rushing stream, discrete acts of consciousness and their objects arise and pass away co-dependently moment by moment, like virtual particles bubbling up out of a quantum vacuum and immediately disappearing again. The process happens so quickly that it eludes normal perception and creates the appearance of continuity and stability we know as “the world”—much as running a film at high enough speed creates the illusion of continuity on the screen because you don’t see the separate frames. When attention and concentration are this refined, and, more importantly, when the mind is willing to let go of its clinging to the need for the world as we know it (this is not just about developing good samādhi—good samādhi depends on relaxing grasping) you see the individual frames. Each act of consciousness (nāma) and its “object,” (rūpa) as a discrete and completely separate event, arises and disappears together, interdependently, one event after the other, nano-second by nano-second, with no “I” or “thing” enduring across the gap between the disappearing of one event and the arising of the next. This is truly a looking glass world where, as the Mad Hatter tells Alice, things are not what they seem!

Each of the following “stages” is just another step backward in seeing and experiencing how consciousness constructs reality like this, moment after moment, from the first moment of “contact” (phassa) between the sense organ and the stimulus, until we bring a full-blown thought, sight, sound, smell, taste, physical sensation, or representation of self into being one nano-second after another. At this most fundamental level, the radical impermanence and selflessness of experience is unavoidable and inescapable. You also experience in each moment how even the slightest reactivity in the mind, the slightest attraction or aversion, causes profound suffering in a world of such complete impermanence and insubstantiality. From being a “truth,” dukkha becomes a “noble” truth here, not just understood but lived in the marrow of your bones. The “inverted views” are righted: anicca, dukkha and anattā are simply “the way things are” in this and every conceivable moment.

WORKING THROUGH: ACCEPTANCE AND SURRENDER

But seeing this and accepting it are two very different things. Each step in this process profoundly shocks our normal mind and temporarily destabilizes attention and concentration. It also confronts us with yet another loss which is difficult to accept. As we continue practice, each mind-moment becomes like a trial in a tachistoscopic experiment in which we are asked to identify some particular feature when a high-speed image is flashed on a screen—in this case an ontological core. And we can’t; over and over again we can’t. We can’t find that core that persists. This is too different from the way we normally experience ourselves and our world.

The real challenge of the ñānas, however, is acknowledging and surrendering to what you now know and see. Practice isn’t just a matter of dispassionate and disinterested observation of mind-moments. This is ME that’s at stake! When the world gets turned on its head like this, it’s an experience of immense loss (even though what it feels we have lost never existed in the first place). When we see the breakup of what we thought was solid and real and enduring and desirable, when we see our own existence slip through our fingers like water through a sieve, we don’t say “Whoopee! Terrific! This is wonderful. I’m finally grasping what the Buddha taught!” That’s not what the experience is about, nor is that the reaction it produces. On the contrary, after some initial exhilaration, it becomes profoundly unnerving as the implications set in. Mindfulness is momentarily shaken each time until it can accept the “knowledge” of each successive ñāna. The next ñāna comes into view only when the experience of the previous ñāna is fully worked through and accepted. This involves the emotions and the will even more than the understanding. As in other transformational processes, insight necessitates the work of mourning. Insight brings you to the door; only your willingness and capacity to leave something long-cherished behind enables you to walk through.

We can’t cheat on this. We have to come to know anything for what it is before we can let go of it—hence the description of each stage as a ñāna or “knowledge.” Trying to surrender without really facing what needs to be faced, or trying to avoid dealing with pain, confusion, fear and sense of loss never works. But not being able to cheat is also what makes it so inspiring and so profoundly real. It has to be real or it’s nothing. There are lots of ways of trying to short-circuit the process: “All right. Take me, I give up, I surrender.” But this is a premature surrender because it’s not based on really facing what needs to be faced and not dealing with the pain, confusion, fear and sense of loss. It never works.

But not being able to cheat is also what makes it so inspiring and so profoundly real. It has to be real or it’s nothing.

The work of mourning—the process by which we let go—tends to proceed in phases, in tandem with deepening insight. If you look at the ñānas this way, you can see that each one involves one of the phases and tasks of mourning work. This helps explain why the “stages of insight” unfold as they do, and why they follow the order they do. As in normal mourning, not every stage is experienced in quite the same way by every practitioner, but the basic structure seems to be the same.

In “dispelling the illusion of compactness,” there is typically an initial feeling of joy and freedom, a burden being lifted. But usually this gives way quickly to instinctive recoil, disbelief, resistance, even denial. In this case, it is not around what you have actually lost, but what you have been unable to find or discovered never existed in the first place—an ontological core to the self. As this reality inescapably sets in, recoil is succeeded by restlessness, the physical pain that comes with contraction and resistance, and feelings of losing control. Without the cherished self to hold onto any more, emotional reactions become unanchored and tend to temporarily oscillate between core feelings of bliss and dread.

Freud described the impulse in the early stages of mourning to hallucinate the presence of the person who has died, as though they had only been “lost” and could be “found”—an adult version of hide-and-seek which we practiced as children to master fears of abandonment and separation. Something equivalent happens at this stage: full-blown imagery and fantasies reoccur in an attempt to recreate a solid world with a stable core. All of this parallels the phase of acute grief in normal mourning.

But attempts at restoration gradually give way to a sense of misery and suffering as the reality of anicca, dukkha, and anattā can no longer be denied. Instinctive disappointment and anger follow—ego’s response to its own pending demise—then sorrow and sadness, and finally some degree of apathy and disengagement from an inner and outer world that doesn’t even offer temporary relief, let alone lasting satisfaction. This corresponds to the phase of withdrawal and psychic disorganization in normal mourning, though here it is observed and undergone with clear mindfulness. This phase is pronounced following the ñāna called “dissolution” (bhanga-ñāna) in which consciousness and its objects are experienced as dissolving nano-second by nano-second, “part by part, link by link, piece by piece,” in which even the arising of mind-moments isn’t apparent; only their vanishing.

But attempts at restoration gradually give way to a sense of misery and suffering as the reality of anicca, dukkha, and anattā can no longer be denied. Instinctive disappointment and anger follow—ego’s response to its own pending demise—then sorrow and sadness, and finally some degree of apathy and disengagement from an inner and outer world that doesn’t even offer temporary relief, let alone lasting satisfaction. This corresponds to the phase of withdrawal and psychic disorganization in normal mourning, though here it is observed and undergone with clear mindfulness. This phase is pronounced following the ñāna called “dissolution” (bhanga-ñāna) in which consciousness and its objects are experienced as dissolving nano-second by nano-second, “part by part, link by link, piece by piece,” in which even the arising of mind-moments isn’t apparent; only their vanishing.

It’s “like seeing the continuous successive vanishing of a summer mirage moment by moment; or the instantaneous and continuous bursting of bubbles on a pavement in heavy rain; or the successive extinction of “candles blown out by the wind” (Ven. Mahasi Sayadaw)—a thousand in the blink of an eye. When nothing remains stable for a fraction of a second, when the radical temporality of all existence becomes overwhelmingly and incontrovertibly clear, the reactions that follow are so pronounced that each comprises a separate stage or ñāna: first fear or “terror” (bhaya) as you might expect; then “misery” (ādinava) as fear gives way to unbearable absence and loss; finally “disgust” (nibbidā) and withdrawal as there seems to be no consolation or satisfaction anywhere. The 16th century Christian contemplative, St. John of the Cross, called this phase “the dark night of the soul” for the same reason: the night is dark because it is overwhelmingly clear that neither God nor the soul nor the self as we knew them are any longer to be found. There is instinctive recoil and withdrawal: nothing seems sufficiently worth doing or caring about without them.

Though the process is profound, there is nothing mystical about it. It is exactly what we would expect.

This is the stage where practitioners in both traditions are most vulnerable to becoming stuck or giving up. It is the point at which mourning is always most vulnerable to becoming blocked. Not through lack of insight, because there is great clarity and an understanding that this is the way things are; but through becoming mired in despondency and despair because it’s so difficult to accept and the way forward isn’t yet clear—even that there is a way forward—or that there is anything beyond this at all. If we get stuck in practice, as in life, it is not around insight, but around grief and mourning.

As these reactions are worked through in turn, a willingness to face reality as it is gradually emerges, and along with it, a re-dedication to practice. At first this brings renewed restlessness and agitation that is part of facing a truth resisted. The final series of ñānas comprise the working-through that completes mourning: a re-finding of the will to continue and face precisely what is most feared; and out of that renewed application and effort, finally a new equanimity (upekkhā). This in turn becomes the basis for a final acceptance of what we have discovered. Though the process is profound, there is nothing mystical about it. It is exactly what we would expect.

Just prior to the moment of full acceptance and letting go, there is one final experience of anicca, dukkha or anattā. For most at first path it will be an experience of dukkha. It is as though the mind needs to convince itself of the truth one last time—”Yes, this is how it is”—before letting go. Whichever truth it is for you, the tradition calls it your “door of deliverance” (vimokkha dvāra) or “door of emergence,” because it leads immediately to the moment of full and complete acceptance and final surrender of any wish that things be different. In the next moment, consciousness ceases to be bound to any object, and stops bringing forth any mental constructions altogether. Consciousness “passes to the other shore.” My teacher called this “the supreme silence.”

When “reality” returns and mental constructions resume, practitioners describe happiness, lightness, joy, a sense of unparalleled freedom and spaciousness, as if a great burden had been lifted. This state of consciousness passes too, however, after a shorter or longer length of time. What the tradition says does not pass are the “fetters” or sources of suffering that bind us to the wheel of life and death which are permanently extinguished in the moment of awakening.