As the morning star rose and the Buddha achieved his great insight, tradition tells us, he saw all at once the matrix of causes and conditions that result in human experience: a swirl of interdependent physical and mental events repeating over and over, creating dukkha (suffering). Because he saw so clearly, he also saw how to end the suffering: nibbāna. One could stop the spinning cycle forever. Its dynamic nature—its seeming strength—was also the gate to freedom.

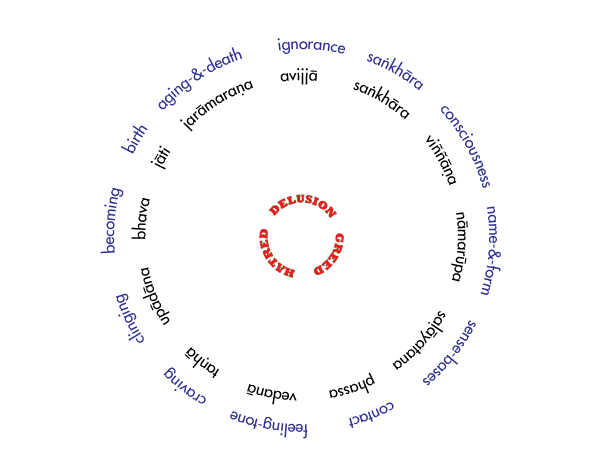

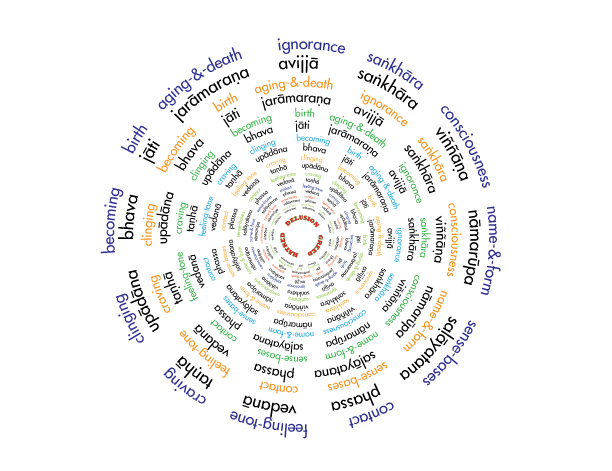

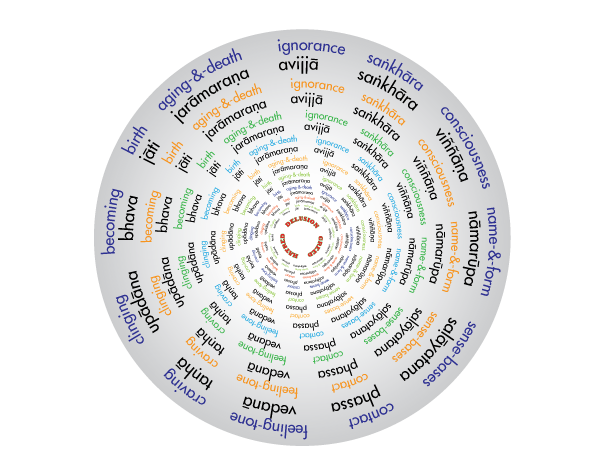

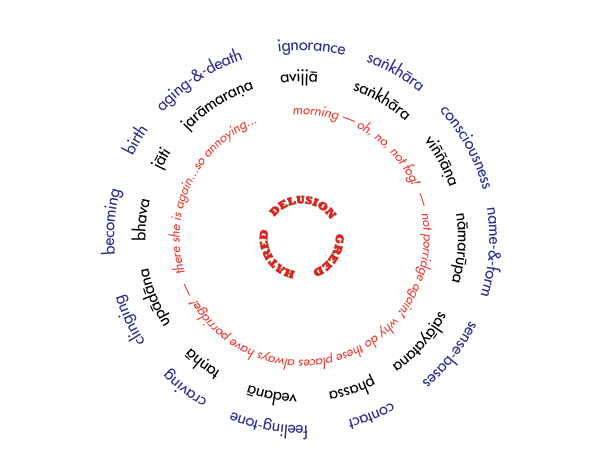

One of the most important aspects of this insight, called paṭicca-samuppāda or dependent origination, is that dynamic nature. Some day I would like to get someone to build me an illustration of the wheel that is actually spinning. It is something that is in process all the time.

By some accounts, the four noble truths are another way of teaching the same understanding of our experience that the Buddha first understood in the form of paṭicca-samuppāda. Once he understood how experience is constructed, he saw the way to the end of suffering. The Buddha says:

“This dependent origination is profound and appears profound. It is through not understanding, not penetrating this doctrine that this generation has become like a tangled ball of string, covered as with a blight, tangled like coarse grass, unable to pass beyond states of woe, the ill destiny, ruin and the round of birth-and-death.” [DN 15, Walshe]

Paṭicca-samuppāda is translated as dependent origination, or codependent arising, or causal interdependence. I will use paṭicca-samuppāda here rather than any of the translations. It is considered by the Buddha to be a universal law governing human consciousness, perception and action. Some of you will have seen this in another form, in one of the mandalas of a Wheel of Life.

What paṭicca-samuppāda is describing is the way in which our personal world is constructed and created, moment to moment. According to the Buddha, human experience is patterned in a way that is clearly discernible to us when we investigate this law. So paṭicca-samuppāda describes not only the way in which our personal world forms and changes and fades away; it also describes the ways in which suffering, struggle and confusion are created and constructed.

Suffering and the end of suffering

Because it traces the arising of suffering, the clues to liberation are also held within this map, so it is also a model of awakening. We see both the problem and the solution within the same map.

We can really understand the profundity and the breadth of what actually is going on in our consciousness moment to moment. Paṭicca-samuppāda explains the core statement of the Buddha, that the causes of sorrow and the causes of joy lie within our own hearts and minds, and within our own understanding or its absence. This is a very practical teaching. It can seem incredibly complex and profound; to understand it can clearly be the work of a lifetime. But on another level, we can get a feel for how this is actually working in our own experience, it reveals a remarkable simplicity alongside its profundity.

You do not need to be a scholar to understand paṭicca-samuppāda. What you need is simply a body and mind and therefore human experience. The Buddha often talks about this as being the heart of all of his teaching. Paṭicca-samuppāda and the teaching of anattā were the two central teachings that truly distinguished the Buddha in his time, that made him so radical.

They were said to be pivotal teachings of liberation because they speak not only about how suffering arises but about bringing the wheel to stillness. In talking about this, the Buddha said whoever sees dependent origination, sees the Dharma; whoever sees the Dharma sees dependent origination, and whoever sees the Dharma sees the Buddha. So if we can get even a little understanding of it, that will be useful.

This is the heart of right view, of wise understanding, and the beginning of the Eightfold Path, which gives rise to a life of wisdom and freedom. The Buddha went on to say that when a noble disciple thus fully sees the arising and cessation of the world as it is, he or she is said to be endowed with perfect vision, to have attained the true Dharma, to possess the initiate’s knowledge and skill.

The contingent nature of things

Paṭicca-samuppāda is describing a natural law, the interdependent nature of all things, the contingent nature of all things. So what is essentially being described in paṭicca-samuppāda is the teaching of contingency, the complex of conditions giving rise to a matrix of experience. This law shows that there is nothing that is separate, nothing that has independent self-existence.

All of life and experience are very much bound up in this wheel. We are affecting, and being affected by, the movement of these conditions in every moment of our lives. What is described in paṭicca-samuppāda is not only the way things are, but the way they can be. In other words, its dynamic nature is the key to the possibility of liberation.

Lifetimes, moments, and determinism

Ever since the time of the Buddha there has been an argument among scholars and practitioners about whether this is a model of a three-lifetime experience, a one-life experience, or a moment-to-moment experience.

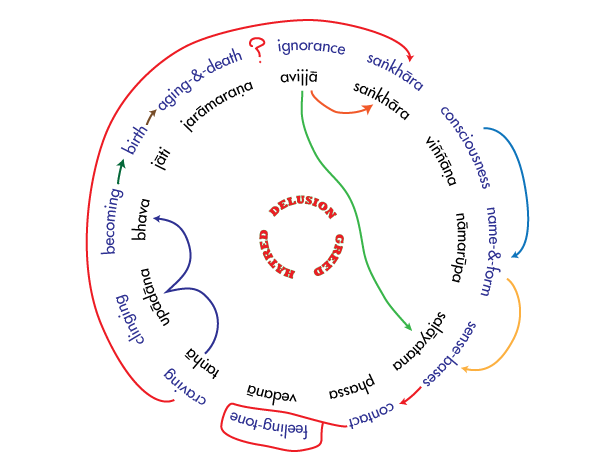

Now I suspect that debate will go on until the end of time, and I have no intention of resolving it. In the three-life presentation of this teaching, what you have is ignorance and volition being carrying forward from the past life to this life; then in this life, we have body-mind, consciousness, senses, contact, feeling, craving, clinging, becoming, which then take us into another birth, all creating a forward momentum.

The presentation of dependent origination I will be focusing on here is to look at the ways that we spin the wheel moment to moment, day to day. To understand how our world of the moment is constructed and patterned is to see in our own experience how suffering can come to an end and freedom can be found. This is a teaching of great immediacy, asking us only to look within our own minds and experience.

The Buddha invited investigation of the life we are living in this moment to discover the degree of freedom—or not—we may experience within it. So what the Buddha was talking about was not even a one-life experience, but a moment-to-moment experience.

Conditions versus causes

The Buddha did not talk about a causal structure in which one thing simply causes another; that is a very linear way of seeing. What he said is that when certain conditions are present, a certain event will occur. If you look at the weather this morning, you know it took certain conditions to be present for this weather to arrive. If you changed those conditions something else would appear; we would perhaps have a sunny morning or snow. Certain conditions come together, have a certain fruition in a particular event, which in turn changes into other events. If you are ill, certain conditions have to come together for you, so you have a heart problem or diabetes or something else. Change those conditions and a different event will occur.

This is critical, because this is what allows paṭicca-samuppāda to be dynamic, to be accessible, and to be a pathway to liberation. Without this dynamic nature, there would not be a way out. The Buddha only thought of paṭicca-samuppāda in the service of that way out of this endless spinning of the wheel of suffering.

Being taken for a spin

To see this as dynamic, consider how the process has probably occurred for you hundreds of times since you woke up this morning. Ignorance is the background that determined that we did not know what was going on. So maybe you woke up this morning, you opened your eyes and looked at the window, and you saw fog. That is contact. Maybe there was a feeling tone associated with that; perhaps it was unpleasant, because you have an underlying tendency regarding rainy weather.

So the underlying tendency of aversion comes to the surface, conditioned by contact through the sense doors: “No I don’t want this to be happening; I don’t want fog.” Maybe I live in England and I have just come to Florida for sunshine. Now how many wheels have been spun: I go into the dining room, perhaps already feeling a little depressed. Then again the sense doors are activated by what is on the board for breakfast: “Oh porridge, why do these meditation centers always have porridge!” Here comes a little bit of raw aversion: “Why do I always end up with porridge?” et cetera. This is how it works. I am crisscrossing this wheel of paṭicca-samuppāda because it is all different conditions. It is not linear.

So these pieces are always engaged in a dynamic process, not an unbroken circle. The circle is all of these pieces interacting with each other to spin the wheel. Some will have more predominance at one time than another, but all these pieces are interacting with each other to make the wheel spin.

It takes all kinds of spins

Not all these pieces are necessarily a problem. Consciousness, name-and-form, sense doors, contact, feeling, are going to be part of our lives as long as we live. It was the same for the Buddha; his body did not die when he became liberated. You can also say birth and death will be part of everybody’s experience. Becoming, clinging, craving, saṅkhāras—this is what makes life complicated.

It can feel very deterministic, as if our reactions are predetermined and we keep ending at the same place again. The Buddha says that to understand this, to take away the sense of hopelessness, you need to see there is a possibility of stepping off the wheel, which is done by looking at what is optional in this.

When we begin to see the patterns in all the movements—from happiness to sadness, from elation to despair, the content you might have experienced a hundred times already today—it often feels quite mysterious. I do not know how I got there; why couldn’t I stay happy? I was content, but I couldn’t I stay content.

It was not an accident that happiness changed into unhappiness. There were conditions coming into play. There were conditions present for the arising of unhappiness, for the disappearing of happiness. Things do not just happen to us; they are happening within us or from conditions. Many conditions in our life are not in our control. If I mindfully go out for a walk and get hit by a drunk driver, I was not in control of that condition. The conditions of my life and my mind are always interfacing with countless other conditions in the world.

The world and our experience of the world

To say there are no accidents is to talk about what is actually happening within the realm of what we can be responsible for, participate in, cultivate, or bring to an end. We cannot decide to have only pleasant sights and sounds and thoughts; we cannot decide to have only pleasant tastes, smells and body experiences; we cannot decide to make things last. There is much in the world that we simply cannot impose our will upon.

This does not mean we are helpless, because in terms of the path of practice we can make an effort to cultivate other conditions within our consciousness. We can cultivate kindness, ethics, and investigation; these too are conditions that may be introduced into this vast mandala of conditions. These do not control other conditions, but they affect our relationship to the conditions we cannot control.

The conditions we cultivate become the ground for advising us about other events, other ways of experiencing this life we are living. It is important to understand how very immediate this can be: If you go into the dining room and are a little bit grumpy about the fog, you see your experience building into that grumpiness; you know, “Now there is porridge to deal with,” perhaps also difficult people. We see the way we are writing the story of the moment as contact activates underlying tendencies, that in turn shape our perceptions and experience of the moment. If we have some sense of the mental state that is there, we can actually shift it in the moment. We can investigate it; we can introduce some spaciousness immediately. It does not seem like such a long arduous process of chipping away at the core of our discontent.

Using the dynamics of spin to advantage

I am sure you have seen how quickly your experience in the moment can change. This is just as true of our progressive development on the path in this teaching. When you look at the teachings about Angulimala, the serial killer who gets liberated with just a few words from the Buddha, it is a very dramatic story of how quickly change can occur.

But think about what happens if you go outside and decide to take a small creature off the pathway rather than stamping on it. If you have the awareness to do that, to investigate your mental state, perhaps you might see into your irritation with someone right here, right now: You have a moment where you can shift into seeing the wholeness of that person, and you can know the resistance and the aversion falling away. Our capacity to affect the conditions that we are living moment to moment will determine the degree of freedom we experience in that moment. Hopelessness refers primarily to a lack of this sort of investigation, and therefore a diminished sense of our capacity to affect the inward and outward conditions we are experiencing.

This is how the Buddha often presented paṭicca-samuppāda. He said “When there is this, that is; with the arising of this, that arises; when this is not, neither is that. With the cessation of this, that ceases.” That is the basic formula.

When all the spinning cycles of contact, feeling, thought, bodily action and so on are taking place upon the ground of ignorance, this is called saṃsāra, wandering in a dream, perpetually wandering from one state of perception and experience to another. In the Tibetan tradition, the word for saṃsāra literally translates as “walking in circles.” Most of us can recognize this in our lives. This is what the Buddha referred to as patterning. As a result of reactivity, we are patterning experience, reinforcing certain tendencies and misunderstandings.

To the extent those beliefs and tendencies are unexamined, they go on to pattern the world as we understand it. So if I have an underlying tendency toward anxiety, it will pattern my consciousness in a certain way: agitation and restlessness, for example. I see the world full of intruders, threat, menace and insecurity. These patterns become familiar, reinforced neural pathways, habits of mind, belief systems.

When we can sense these patterns in ourselves we can see our personality structures, our sense of identity. Some of it is inherited, such as the mother who worried forever, so I have learned to worry forever. Some of it is very much born from our own life experiences that have shaken us. We see it perhaps in relationship to our families or our spouses, our partners.

Social and other spinning

This process of paṭicca-samuppāda is a process seen not only within our individual consciousness. We have collective spinning too. It can be seen when social, cultural, political groups spin the same wheel over and over again, sometimes for very extended periods of time.

So understanding dependent origination is not only transforming on an individual level but I think it can have an immense impact at the community level. If we think about the major shifts in racism or sexism, somebody had to stop spinning the wheel, which encouraged others to stop spinning a wheel. McCarthyism shaped the minds of a generation, and we have stopped spinning that wheel. Now we are spinning the wheel of terrorism, or of a purely materialistic view of society. We have various kinds of agreed spinnings: religious systems, political parties, wars.

So this is what the path of investigation is all about. It is not to say that all collective thought processes or feelings are unwholesome; sometimes in families, or together here at BCBS, we collectively spin a certain wheel. There will not be a time in our world where wheels are not spun. The real question is about investigation. Is it wholesome or unwholesome? Does it lead to the end of suffering, or does it perpetuate suffering? Is it rooted in ignorance? Is our spinning generating the fuel that leads to further spinning—craving, clinging, greed, hatred—or is it calming the spinning?

When the Buddha brought forward this teaching he was equally concerned with the state of his culture as with sustaining peoples’ minds. Bringing forth this teaching was not only about changing the mind; it was also about changing the world he lived in. Of course, if one gets too attached and ambitious—” I am going to change the world”— being disheartened follows very quickly.

In the Tibetan tradition there is a saying:

Do not disregard small misdeeds,

thinking they are harmless,

because even tiny sparks of flame

can set fire to a mountain of hay.

Do not disregard small wholesome deeds

thinking they do not matter.

Great oceans are filled drop by drop.