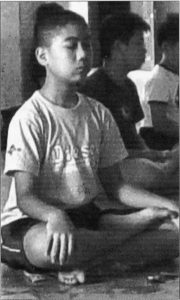

The adults in the Zen commune I grew up in for a time may have been nutty, but they were brilliant in their approaches to teaching the children of the commune about meditation. There was nothing systematic or planned about how kids got lessons in mindfulness. Yet, all of us commune kids by the age of seven could meditate for a half hour, knew Japanese chants, zendo etiquette, and could do a full form from tai chi chuan—and even saw all of it as fun, as a game.

The adults in the Zen commune I grew up in for a time may have been nutty, but they were brilliant in their approaches to teaching the children of the commune about meditation. There was nothing systematic or planned about how kids got lessons in mindfulness. Yet, all of us commune kids by the age of seven could meditate for a half hour, knew Japanese chants, zendo etiquette, and could do a full form from tai chi chuan—and even saw all of it as fun, as a game.

I have organized these informal lessons together into a progression, based on what worked for me as a kid and on what I see works for others. The following series of mindfulness games and exercises is based on the lessons I received. This is still a work in progress, and I welcome any reflections from readers, especially those who work with different age groups, on how to improve it.

In my experience, telling a beginner to “watch the breath” is too abstract. Thus this program moves from the things we immediately perceive with the gross senses, such as hearing, touching and tasting towards more subtle things, like the breath. This sets a foundation for moving from awareness of the breath to awareness of the more ephemeral emotional and thought processes. The following activities are done in a group (size doesn’t matter). This version is written for a 11-13 year old public school audience, so I’ve kept the language simple and without reference to the Buddhist meditative traditions from which the exercises are drawn.

Mindfulness of Hearing: “How Many Sounds” Contest

- Okay, everyone, close your eyes and for one minute listen for as many sounds as you can. [Minute passes.] Open your eyes. Without talking, write down everything you heard. Who got more than ten sounds? More than twenty? [Person with the largest list reads theirs aloud.]

- Let’s do it again. Close your eyes, and for one minute, listen for as many sounds as you can. [Minute passes.] Open your eyes. Again, write down everything you heard. How many of you have a second list that’s longer than the first one? [Everyone will.] Would someone like to read their list?

- Lesson: Wonderful. Mindfulness is like a muscle: the more you exercise it, the stronger it gets. You managed to improve your ability to perceive sounds in just ONE minute. Isn’t that amazing?! And, you know, this attention muscle is the same muscle that does the heavy lifting of studying, figuring out math problems, writing an English paper, and so on. So, if you practice meditation regularly, you’ll find you can sustain your attention during studying for longer periods and with higher quality.

Mindfulness of Tasting: Raisin Meditation

Give everyone two raisins. I use golden raisins just to make it a little more exotic. A bowl with the raisins can be used, supplying a spoon so that too many grubby fingers don’t get into the bowl.

- We’ve just brought our attention to our ears, so now we’re going to bring it to our mouths. I’d like you to chew one of the raisins as slowly as possible, for at least three minutes. Okay, let’s start—don’t put the raisin in your mouth just yet! Take one raisin in your fingers slowly. Look at it carefully, the color, the way the light hits the folds. Feel the pressure of your fingers against the sticky skin. Close your eyes, and very slowly bring the raisin into your mouth and begin to chew and experience it there.

Generally, students will take about four minutes with the raisin. You can get a sense of when to stop by looking at how many are still moving their jaws.

Okay, go ahead and swallow the raisin if you haven’t already. So, what kinds of experiences did you have with the raisin? [Depending on group size, you can go around in a circle, or you can have kids raise their hands.]

By the way, guess how long you guys chewed that raisin for? One minute? Two? Nope! You chewed it for FOUR minutes!

The kids will be amazed.

- Let’s do it again. This time, what I want you to do is to think of your mind as a microscope and I want you to see how strong your microscope can magnify your experience of eating the raisin. While you’re chewing this raisin, try to get down to the smallest particle of sensation. I want you to be like a scientist, looking for the tiniest atom of raisin-chewing experience.

Take the second raisin in your fingers, again looking at the color, the texture. Bring your awareness to your mouth: can you feel your mouth preparing itself for the sweetness? I just felt my mouth water. Close your eyes and bring the raisin to your mouth.

Generally, the students eat the raisin more quickly the second time, but this will still take several minutes.

Okay, go ahead and swallow the raisin if you haven’t already. Would anyone like to share what their tiniest atom of raisin-experience was?

- Lesson: Isn’t it amazing that something as simple as chewing one single raisin can open up an entire world of sensation? I’d like you to remember the last time you had, say, a scoop of your favorite ice-cream. Someone tell me what your favorite kind of ice cream is: (chocolate, vanilla, etc.). Great.

So there you are with your scoop of ice cream, and the first bite, isn’t the first bite just so wonderful? It just explodes in your mouth, all that sweetness and cold and melting. But, then, think about the last bite of ice cream. Are you even aware of the ice cream by then?

Somehow, as you dug through the ice cream, your attention got distracted. Maybe you were watching TV or you were talking to someone. The initial burst of sensation of the first spoonful of ice cream has diminished to the point where we’re not even aware of the ice cream any more.

Well, this says something about how we experience pleasure. And what happens in bigger things in life is that we have to keep ramping up our pleasurable experiences to get the same high. So the next time we get ice cream, we might get a sundae, and the time after that, we might get an entire banana split with oozing chocolate and M&M’s and three scoops of ice cream. I think you’ve seen adults do this, for example: they might start with a canoe, and then a few years later it’s a motor boat, and a few years after that it’s an entire yacht.

Well, guess what? If you bring mindfulness to your experience, you can enjoy the last bite of ice cream as much as the first. This way, you can keep your life simple: you don’t need an entire banana split to get the same high off the ice cream if you are totally mindful of the pleasure that one scoop can bring. In fact, I bet you will feel more satisfied, more fulfilled from that one scoop if you eat it totally mindfully, than if you ate the whole banana split thoughtlessly.

So what this means is that mindfulness can help us regulate our consumption, not just with food but with video games, movies, or anything that we often consume for pleasure. It helps us be more healthy and balanced with our intake.

Note: Invariably, someone in the group will not like raisins, and this can be used as a point about distinguishing between the bare experience of tasting the raisin versus the mental activity of disliking and judging about the raisin.

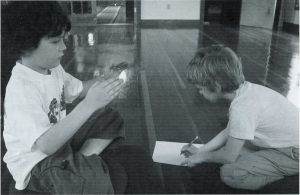

Mindfulness of Movement I: Palms Together

Have students pair off and sit facing each other. Everyone will need a sheet of paper and writing implement.

In this activity, we’re going to bring our mindfulness to movement. One of you is going to do a simple movement and verbally report on all the sensations of that movement. The other person in your pair is going to be the secretary, writing down what you say. The movement we’re going to do is to bring our hands from resting on the knees up to a palms-together position in front of our chests. Teacher should demonstrate and verbalize: I feel the warmth of my palms on my knees (the secretary can write down “warmth of palms on knees “). Now I feel my biceps contracting. I feel the cool air under my palms as I lift them in the air. …. I feel my fingers coming together…. Move very slowly so that you can feel as many sensations as possible.

Activity usually takes 10 minutes. Who would like to read the movement journal of their partner? Someone reads. Would anyone else like to share? Okay, let’s switch roles. The other person is the secretary and you can be the person doing the movement. Have the sharing again.

Mindfulness of Movement II: Walking Meditation

Have the students line up after you, the teacher, and walk around the room, very slowly, in a circle. With shoes off, students can feel the floor and their feet more sensitively. Teacher guides by asking questions throughout: “what part of the foot leaves the floor last? What part of the foot comes to the floor first? Can you feel your toes spreading as you put more weight on the foot?” 8-10 minute activity.

BREAK Students will need to stretch out, chat, release some energy. Good time to have lunch. Some will naturally do a mindfulness of eating at lunch.

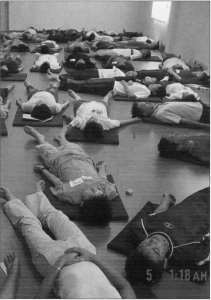

Mindfulness of Body: Full Relaxation and De-Stressing

Welcome back, everyone. So we brought our attention to sound, then to taste, and then into the motion of our hands coming together. Now we’re going to bring our attention into our bodies and consciously relax each part of the body, releasing any built up stress and tension. Our minds are not separate from our bodies: when our mind is tense and full of racing thoughts, our bodies become tense and stressed out. Likewise, when we relax the body, that sends a message to the mind to relax, to slow down. As your body relaxes, you’ll find that your mind softens and relaxes, too. So, everyone find a spot on the floor and lay down on your backs. No need to engage with your friends at this point, no need to talk to anyone. Please respect each other by not touching or poking. Lay down with your legs and arms flat on the floor.

The palms of your hands are facing upwards towards the ceiling. Let the feet fall away to the sides, letting your entire body just fall into the floor. Close your eyes and mouth and bring your attention into your body. Feel the contact of your body with the floor, the hardness, the coldness, the warmth, whatever you feel.

Depending on how much time you have, you can do large chunks of the body or small parts, i.e. the entire foot versus the toes, the foot, the ankle.

Bring your attention to your feet and consciously relax all the muscles. Let the feet fall to the sides without any effort. Completely letting go of any strain, feeling the muscles become soft and relaxed. Now feel the muscles in your calves, letting go of any tightness or strain, allowing the muscles to become soft and relaxed. Allow your entire head to just fall into the floor, very heavy, very soft, melting into the floor teacher’s voice should soften, become rhythmic in instruction.

There are actually a variety of relaxation methods. One is a way of autosuggestion: “My feet are relaxing, my feet aaarrree relaxing, my feet are relaxed.” If you are familiar with a technique from yoga classes, just use that. Anything will work!

Move to knees, thighs, bottom, pelvis, back, abdomen, chest, down one arm to the hand and then down the other, the shoulders, neck, back of the head, area around the mouth, cheeks, area around the eyes, top of the head, the whole head. Minimum 15 minutes of full relaxation.

Now let your awareness spread throughout your entire body, allowing everything to completely relax, heavy, soft, falling into the floor.

Be silent for a few more minutes, letting the children be in their bodies. Most will fall asleep, which is fine.

Be silent for a few more minutes, letting the children be in their bodies. Most will fall asleep, which is fine.

Now, let’s re-awaken our bodies by gently moving the fingers. No need to talk or interact with your friends, just stay inside yourself. Gently wiggling the toes. Move your head slowly from side to side. Now slowly roll over onto your left side. Take a rest there, just feeling how calm and relaxed you feel. Now slowly push yourself up into a sitting position. Please respect others by not interacting with them, just stay inside yourself. For those who ‘ve fallen asleep, have an assistant teacher gently wake them up.

And now come into a sitting position, close your eyes, and feel your whole body, how relaxed it is.

Teacher should keep voice soft, be very still, sitting in similar position to model for children. Move right into next activity.

Mindfulness of Breath

Feel your body, feel your bottom touching the floor, your ankles touch the floor and your calf. Feel your hands on your knees. Let your awareness be in your entire body, just moving from sensation to sensation. Do this for a few minutes.

And now bring your awareness into your abdomen area, feeling it move as you breathe. …

Moving your awareness into your chest, feeling it rise and fall as you breathe. No need to control the breath. Just let it come and go as it will. Sometimes the breath will be long, sometimes short, sometimes deep, sometimes shallow. Just let it be and watch….

Moving your awareness to the back of the throat, feeling the air pass there, very soft and gentle

Moving your awareness to the back of the nose area, feeling the air passing in and out, warm and cool, in and out….

Moving your awareness to just inside the nostrils, feeling the air there passing in and out, warm and cool….

Moving your awareness to the tip of your nose, feeling whatever sensations are there. Your mind is alike a microscope, zooming in on the smallest of sensations, finding the atom of sensation….

Now watch your whole breath, letting your attention go to wherever in the breath it wants, the nose, the throat, the chest, the abdomen, just letting the attention be with the breath, very soft, very gentle, very light, very quiet….

Most of the children will be completely absorbed in this for at least five to ten minutes. Some of the children will naturally break their attention and begin looking around. To let the ones really absorbed be with that as long as possible, be patient and try to make the time go as long as possible, perhaps ten minutes. For those with their eyes open, you can just smile at them and indicate they should keep silent (finger to lips sign) which will reassure them that they ‘re not in trouble but should respect the others. When a critical mass of children have broken their concentration, close the meditation, as follows:

Keeping the eyes closed, bring your attention to the palms of your hands, feeling them there. Slowly lift them and feel the movement as your bring your palms together in front of your chest, feeling all the sensations like we did before. And now bring your hands back to your knees. Open your eyes to look just in front of you. Take a nice big breath. And now open your eyes all the way.

Give the students a big smile and look around the room. Teacher should stay quiet and relaxed, matching the energy of the room.

Good job everyone. Guess how many minutes you watched your breath for? Two? Three? Nope! You did that for TEN whole minutes!!

Notes for Teaching

For true beginners, I found that the more the teacher demonstrates, the better the results. For example, when demonstrating the mindfulness of palms coming together activity, the kinds of experiences you note will be a model for the students:

Warmth of palms on the knees

Contraction of biceps

Cool air under the palms

Inevitably, these will be the things that the students list when they do it. But, if you are more detailed in your noting, that leads them to be more creatively detailed in theirs:

As my fingers separate, feeling the moisture between them cool off

The twitching of my left fourth finger

A ripple of muscle contraction in my shoulder

Still, students will need more encouragement to find their own experiences, see if they can come up with something unique that you haven’t said.

On the last teaching session, I tried making things more of a race to see who could do it the slowest (the kids seem to get the joke). “Let’s see who can move their hands the slowest….”

Variations of this series have worked successfully with teens in Malaysia, children in Singapore, young adults from Korea, university students, and most recently, seventh and eighth graders in rural Massachusetts.

Mindfulness for Equanimity and Emotional Intelligence: Short Talk

Good work, everyone. We’ve gone from tuning our attention to sounds, to tasting, to feeling movement, to our entire body, and then to the breath. Now I bet you’ve never thought about this, but breathing is a very special part of our being. Here’s why. As you know, with our bodies there are things we can control and things we can’t control. For example, we can control moving our fingers but we can’t control our heart beating. The heart will beat by itself. But there are a few things in our body that are both automatic and to some extent in our control. Think about blinking, for example. You blink without even thinking about it. Somehow your body is set on automatic to blink regularly to keep your eyeballs moist. But you can also control your blinking. If I say, “blink five times fast” you can do it, right? Breathing is like blinking: we breathe most of the time without even thinking about it. And at the same time, if I tell you, “Take a deep breath in” you can do it consciously.

In this way, the breath can be a link between our body and our mind. In fact, our breathing often reflects our state of mind. When you are afraid, your breathing becomes short and tight, and resides in the chest area. When you get surprised, you will take a quick, sharp breath into your throat area. But, get this: you can use your breath to control your state of mind. Let’s do an experiment. I’d like everyone to put one hand on the belly and one hand on the chest. Now take a slow breath in, first letting the belly-hand rise and then draw air up into the chest, letting your chest-hand rise. Good. Now slowly breath out, letting the chest-hand fall and then letting your belly-hand fall. Notice what your mind feels like: calm, relaxed, unworried. That’s why when kids get mad a teacher might say, “Slow down, I want you to take three deep breaths.” It really works: three deep breaths calms our mind down.

And this is one reason that in meditation we use the breath as an anchor for our attention. We can place our attention on anything: on sound, on the taste of a raisin, on the body. But paying attention to the breath has an incredibly deep affect on the mind, giving it calmness and clarity.

Now there’s one more leap from the breath that our attention can take and that is that our attention can become mindful of our very own mental states, emotions, and thoughts. If we practice watching our breath, over time, our attention becomes really strong. Remember how in the second minute of listening for sounds you heard more sounds? Was it because suddenly there were more sounds to be heard? No. It’s because your attention got stronger and so you perceived more sounds. In the same way, with a strong mindfulness muscle, we become more perceptive about our own thoughts and emotions.

Mindfulness in Everyday Life: Homework Assignment

Mindfulness is a tool that you can carry with you everywhere. It’s not heavy. It’s inexpensive. And you can use it in almost every situation. Let’s say you’re in the car, waiting for your mom or dad as they put gas in the car. What do most of you do? Take out a cell phone and make a call, or perhaps send a little message to a friend? Maybe you turn on the radio and fiddle around with it? Basically, most of us will do anything except for sit there and be quiet, being present with our immediate environment. We crave stimulation and hate boredom. But here is a perfect opportunity to try something different. While you’re waiting for your mom or dad to fill up the tank, close your eyes and play a game of discovering how many sounds you can hear. Can you hear the gurgle of the gas going into the car? The beeping of the machine when the credit card is approved. The receipt being printed.

So, here’s your homework: find one regular activity or moment and use that moment to be fully mindful of what’s going on. Maybe it’s waiting for someone to fill the car up with gas. Or maybe it’s putting on your socks. You can put on your socks with total attention to the feeling of cloth against your skin, the pressure, your fingers, your toenails scraping the inside, and so on. For me, I often practice mindfulness of shampooing my hair and brushing my teeth. So that’s your homework, and I promise it won’t be graded.

Closing with Lovingkindness

We’ll end with one last short activity. I’d like you to think about something you own that you really care about. Maybe it’s your favorite pair of pants, or a baseball mitt, or a book you’ve read many times. Now if I were to ask you to describe that thing to me, you’d be able to tell me every single last detail about it, right? For example, these pants I’m wearing. These are my favorite pair. I can tell you about the small threads here where a dog put his paws and ripped it a little. There’s a thread at the bottom coming loose. These pants are 1% lycra, so I can’t put them in the dryer. I know that if I wear them three times without washing the knees get slightly out of shape, but if I iron them again the knees will come back properly. The tiny little pen mark that I can’t seem to wash out.

The point is that the things we love and care about we pay attention to. And very often, the things we pay attention to we come to love. For example, in my grandmother’s house there’s a painting that I used to think was pretty ugly. Well, I’ve had to pass that painting by for about the last ten years and because I’ve seen it so much, I actually have a little bit of affection for that painting. I once read about a famous artist in the Middle Ages who trained his art students by having them draw a decaying fish for three days. You should see these drawings: they are absolutely amazing. Disgusting, but amazing. One of the artists wrote in his journal that although he was at first repulsed by the decaying fish, after drawing it for three days, he came to see that it was beautiful. And that was without refrigeration! So love and attention are two sides to the same coin.

This morning, we’ve done a lot with our attention, learning about it, making it stronger. Now we’ll close with just a little bit of love, the other side of the coin. Close your eyes and bring your attention inside yourself. Settling in to a comfortable, relaxed position. It’s okay to lie down if you prefer. Just make yourselves very comfortable.

We’re going to repeat three phrases silently in our minds:

May I be happy.

May I be peaceful.

May I be free from harm.

Teacher repeats these three phrases at least 3-4 times. It is helpful to add some guidance such as:

“I truly and sincerely wish: May I be happy….”

“With all my heart, I wish: May I be happy…”

“With all my good intentions, I hope that: May I be happy…”

“Remembering that I am a good person, full of kindness, intelligence, humor, generosity, I wish for myself: May I be happy…”

Now, without opening your eyes, think of the person to your right. “Person to my right, whether I know you well or whether I know you only a little, I truly and sincerely wish for you, “May you be happy. May you be peaceful. May you be free from harm. Just as I wish for myself these things, I wish for you….’May you be… ‘” Do 3-4 times.

Now, without opening your eyes, think of the person to your left: “Person to my left, whether I know you well …” Do 3-4 times.

Now thinking of our teachers here with us today, with all the care and attention they give us, “Dear teacher, I wish for you….

Thinking of all our classmates here in this room….phrase can change to “May WE ALL be happy….”

Finally, let’s think about the whole school. Everyone here having joys and sorrows, challenges and successes. The children who come here, the dedicated and kind teachers, the people who make our food and feed us, the janitors who clean the hallways and shoveled the snow today, the secretaries, the administrators, everyone in our whole school, who are all good people, let us wish for everyone, “May we all be happy….”

When finished, let there be some silence.

Okay, open your eyes and come into a sitting position. Wonderful, very good everyone.

And then the teacher can close with:

You have been such a great group to work with. Thank you for your wholehearted effort. I truly wish for each of you here, “May you be happy…” something of a final word from the teacher, giving lovingkindness to the children.

A word about discipline: A very important point regarding discipline: if a student is out of line, giggly or slouchy or keeps their eyes open a lot, that’s OKAY. In my experience so far, because of the nature of these activities, scolding or sternness is not appropriate.

Students open their eyes because they’re uncomfortable. In that case, just smiling at them and then signaling to close the eyes gives them enough reassurance that they’re safe with you. Or, I found just placing my hand on their shoulder helps them calm their body down.