There is, on Himavat,

king of mountains,

a rugged and uneven land

where monkeys do not wander

—and nor do men.

And there is, on Himavat,

king of mountains,

a rugged and uneven land

where monkeys do indeed wander

–but men do not.

And there is, on Himavat,

king of mountains,

a level stretch of ground, quite pleasing,

where monkeys do wander

–and so do men.

There a hunter set a trap

on the trails used by the monkeys,

in order to capture those monkeys.

There were monkeys there who were

There were monkeys there who were

not of foolish nature,

not of greedy nature.

Seeing that trap, they stayed well away.

But there was one monkey

of foolish nature,

of greedy nature.

He went up to that trap

and grabbed it with his hand.

It got stuck there.

“I’ll free my hand!”

“I’ll free my hand!”

He grabbed it with his other hand.

It got stuck there.

“I’ll free both hands!”

He grabbed it with his foot.

It got stuck there.

“I’ll free both hands–and a foot!”

He grabbed it with his other foot.

It got stuck there.

“I’ll free both hands–and both feet!”

He grabbed it with his snout.

It got stuck there.

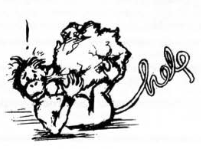

And now that monkey,

caught five ways,

lays himself down and howls.

Fallen into trouble,

fallen into ruin,

for the hunter to do with as he pleases.

This is what happens to one who

wanders in wrong pastures,

in the habitat of others.

Therefore, monks, do not

wander in wrong pastures,

in the habitat of others.

Wandering in wrong pastures,

in the habitat of others,

Mara will gain an access,

Mara will gain a footing.

And what, for a monk, are

wrong pastures,

the habitat of others?

The five strands of sense desire.

What are these five?

Forms discerned with the eye

—appealing, pleasurable,

yearned for and lusted after.

Sounds discerned with the ear

—appealing, pleasurable,

yearned for and lusted after.

Odors discerned with the nose

—appealing, pleasurable,

yearned for and lusted after.

Flavors discerned with the tongue

—appealing, pleasurable,

yearned for and lusted after.

Touches discerned with the body

—appealing, pleasurable,

yearned for and lusted after.

These, for a monk, are

wrong pastures,

the habitat of others.Wander in right pastures,

in your own natural habitat.

Wandering in right pastures,

in your own natural habitat,

Mara will not gain an access,

Mara will not gain a footing.

And what, for a monk, are

right pastures,

your own natural habitat?

The four foundations of mindfulness.

What are these four?

Here, monks, a monk abides:

Observing body as body

—ardent, mindful, fully aware, leading

away unhappiness and worldly worries.

Observing feelings as feeling

—ardent, mindful, fully aware, leading

away unhappiness and worldly worries.

Observing mind as mind

—ardent, mindful, fully aware, leading

away unhappiness and worldly worries.

Observing mental phenomena

as mental phenomena

—ardent, mindful, fully aware, leading

away unhappiness and worldly worries.

These, for a monk, are

right pastures,

your own natural habitat.

Alas, this cautionary tale does not have the happy ending we would like of such fables. In fact, as a childhood fan of Curious George and with a certain affection for (and resemblence to?) this foolish monkey, I could not bring myself to translate what the hunter does to him upon his arrival. The Buddha was not one to pull any punches, especially when an important point of training for the monks was at stake.

Alas, this cautionary tale does not have the happy ending we would like of such fables. In fact, as a childhood fan of Curious George and with a certain affection for (and resemblence to?) this foolish monkey, I could not bring myself to translate what the hunter does to him upon his arrival. The Buddha was not one to pull any punches, especially when an important point of training for the monks was at stake.

The story is taken from the Satipaṭṭhāna Saṃyuttam, a collection of discourses which discuss the Foundations of Mindfulness, root teachings of the vipassanā meditation tradition. The message is one that has much to do with the application of “wise attention” (yoniso manasikāra), and involves changing one’s frame of reference through which sense experience is received and processed.

If we give our attention to the appeal or the pleasurableness that accompanies sensory experience (the sticky trap), then we are necessarilly caught by the perceptual object. There can be no freedom of mind, because we are subtly (and usually unconsciously) yearning for more gratification than the transient object is capable of delivering. Instead of satisfying our desires, such experience merely stirs up more desire. This is the situation most of us take as normal—we seek satisfaction of desire through the pursuit of pleasure in the realms of the senses.

The monastic ideal that so thouroughly shaped the flavor of early Buddhism involves a wholly different way of relating to experience. The idea is not that monks are to avoid or ignore the data that comes in through the five sense doors—indeed this is hardly possible, since all of our sensory experience must pass through these gateways. Rather the instruction is about not getting attached to sense pleasures, as the poor monkey gets stuck to the monkey trap. Sense data itself is not harmful, but the sweetness of pleasure in which each sense input is wrapped is the factor that gets us caught, due to our “foolish and greedy nature.”

The difference in strategy, where a monk is “wandering in the pastures” of the four foundations of mindfulness, is the presence of equanimity. Vipassanā meditation trains us to attend more dispassionately to the nuances of experience. When we simply observe, “mindful and fully aware,” then we begin to undermine the mechanisms by which the mind gets stuck to the objects of our experience.