Most practitioners of insight meditation are familiar with the four foundations of mindfulness, and know that the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta (M 10; D 22), the Discourse on the Foundations of Mindfulness is the cornerstone of the vipassanā [insight meditation] tradition. The first foundation, mindfulness of the body, has to do with bringing awareness, attention, or focus to breathing and to bodily sensations. The second foundation of mindfulness, mindfulness of feeling, involves noticing the affect tone—pleasure or displeasure—that comes bound up with every sense object, whether a sensation or a thought. These first two movements of mindfulness are by and large descriptive; they are merely directing us to notice the texture of what is arising in experience.

With the third foundation of mindfulness, mindfulness of the mind, it becomes a little more evaluative. We are asked to notice, when there is attachment present in the mind, that the mind is attached. When that attachment—also known as greed or wanting—is not there, we notice that the mind is not attached. The same thing happens with aversion, also called hatred or resistance. If it is arising in the mind, then we can notice that the mind is beset by aversion. If it is not there, then we notice that the mind is without aversion. The idea is not, as I understand it, to compare the two states of presense and absence. But one cannot help, on an intuitive, almost cellular level, to begin to discern the difference between what it feels like: what you know about yourself in the world when the mind is beset by attachment or aversion, and when it is not. The same process is outlined for confusion or delusion.

third foundation of mindfulness, mindfulness of the mind, it becomes a little more evaluative. We are asked to notice, when there is attachment present in the mind, that the mind is attached. When that attachment—also known as greed or wanting—is not there, we notice that the mind is not attached. The same thing happens with aversion, also called hatred or resistance. If it is arising in the mind, then we can notice that the mind is beset by aversion. If it is not there, then we notice that the mind is without aversion. The idea is not, as I understand it, to compare the two states of presense and absence. But one cannot help, on an intuitive, almost cellular level, to begin to discern the difference between what it feels like: what you know about yourself in the world when the mind is beset by attachment or aversion, and when it is not. The same process is outlined for confusion or delusion.

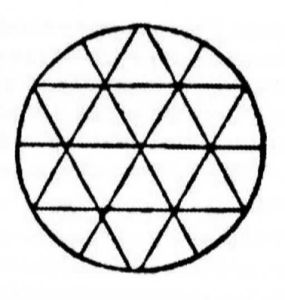

Now with the fourth foundation of mindfulness, mindfulness of mental objects or of mental phenomena, we are sometimes told in meditation instuction to simply notice when a thought arises, be mindful of it, and allow it to pass away unobstructed. There is nothing wrong with this, of course, but actually the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta is directing through a much more precise exploration of the inner landscape of mental experience. What I want to do here is walk systematically through the classical training on how to work with the content of one’s mind, and invite you all to linger experientially on the texture of each step. Almost as a guided meditation, the fourth foundation of mindfulness investigates 108 mental objects, and in the process manages to guide the meditator through the whole curriculum of Buddhist psychology: five hindrances, five aggregates, six sense spheres, seven factors of awakening, and four noble truths.

This goes beyond passive observation into the realm of transformation.

These are subjects familiar to all students of Buddhism. But in working with them as objects of meditation we are asked to look not just at their presense or absence in the mind, but also at how these factors are in motion. And in practice we are directed by the text to working with the arisen mental states in particular ways: when they are hindrances we want to loosen our attachments and abandon them; when they are factors of awakening, which are beneficial for the growth of understanding, we are invited to learn how to cultivate, develop and strengthen them. This goes well beyond an agenda of passive observation of phenomena, and takes us into the realm of transformation.

The Core Terms

The two most important words throughout the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, and which thereby are most crucial to meditation practice, are the verbs anupassati and pajānāti. It is useful to look carefully at these terms in the beginning, to see just how they are to be understood.

Anupassati is often translated (by Nanamoli/Bodhi, Walsh, and Horner) as “contemplate”: e.g., contemplating body as body, contemplating mental objects as mental objects. The earliest translator of Pali, T.W. Rhys Davids, uses the term “consider.” But I think both these words have a meaning in English that suggests a discursive “thinking about” or “pondering over” an object, rather than the sense of direct awareness that is so obviously prevalent in the practice of meditation. These words also fail to capture a nuance in the Pali which can be glimpsed from an analysis of the word.

Anupassati is made up of two elements: passati is simply the verb to see; the prefix anu– adds a sense of “following along” with something. Anu– is used to suggest following along with the way things are already happening. For example anu-loma means “along with [the way] hair [is growing]” while pati-loma means “against [the way] hair [is growing].” In English we would use the expression “with the grain” and “against the grain.” So as a meditation instruction, I take anu-passati to suggest a non-interfering observation or surveillance of what is arising and passing away in experience. In this case, one is following along, not literally with the eyes, but following along figuratively with awareness or attention. I would therefor suggest taking the verb as “to observe” or “to notice.”

A more dynamic view of mind unfolds as the practice progresses.

It’s almost as if these mental objects or the feelings or the body sensations are like little mice that are scampering across the room. They emerge out of one hole, and they run across the floor, and then disappear down another hole. The yogi, the one who is undertaking this practice of cultivating mindfulness, is someone who abides, dwells, or holds herself in the moment in such a way that she is observing the passing of that thought or sensation. She is not contemplating it as much as merely observing it. To observe mental objects as mental objects, then, involves observing their presence, their absence, their arising, their passing away, and observing what happens in our experience with some of these mental objects when we relate to them in a certain way.

The other important word, which lies at the very core of almost every sentence in the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, is pajānāti. It is the Pali term that describes how a meditator relates to each of the objects of experience he is observing. Bhikkhus Nanamoli and Bodhi (who in my opinion generally provide excellent translations) translate by saying he understands ‘I breath in long’ or ‘I breath in short’ (for example); Walsh renders this he knows, while I.B. Horner offers us he comprehends.

Again, I think these are unfortunate word choices, because in English these terms suggest already some wisdom, some contextualization, some association, some piecing of that sensation in with other aspects of one’s understanding. Such a growth of insight and wisdom is certainly something that develops from the practice, but I think in these instructions we are being guided towards a more elemental or primordial mental process. T.W. Rhys Davids seems to agree by using the phrase he is conscious (of breathing, for example). I think the common expression he is aware does the job well for the contemporary practitioner. Awareness is meant not in the sense of a broad, background awareness, but as the deliberate focusing of awareness on a particular object of experience.

What the Satipaṭṭhāna text is inviting us to do—again and again and again—is be aware of this, be aware of that, be aware of the other thing. And in the tour of the fourth foundation of mindfulness we are about to undertake, we are being asked to be aware of certain contents, if you will, of our mind. Although, of course, in Buddhism the mind is not a subject that has objects as content, but is rather the activity or process of observing a flow of events, the unfolding of certain occurrences or episodes of cognition that follow one after another to make up the texture of our experience. This more dynamic view of mind unfolds as the practice progresses.

Working with the Hindrances

The first thing the fourth foundation of mindfulness invites us to do as we observe mental objects as mental objects is to be aware when there is some form of sense desire occurring in experience. One notices, and may even say subtly to oneself, ‘There is sense desire in this moment’. If this is what is happening in the mind, then one is to be aware of it. This sense desire does not need to be a full-blown outbreak of passionate, lustful attachment so often mentioned in Buddhism as the cause of suffering. The hindrance of sense desire is sometimes just a very subtle impulse, rooted in our sensory apparatus itself, to reach for an object or to reach for sensory gratification. Our body wants to feel good; or sometimes, believe it or not, it wants to feel bad. Our eyes want to see, our ears want to hear. Notice the wanting. Be aware of the wanting so often occurring in this present moment at this very basic level of sensation.

And, if you notice it is not there, then notice that. In this particular moment you are observing, at least, the wanting of one particular sense object or of some particular form of gratification is not there. Sometimes it is, sometimes it’s not. Sometimes the eye is wanting to see and sometimes it’s not. Of course, sometimes the eye is not wanting to see because the ear is too busy wanting to hear. The text is inviting you to explore the texture of wanting as it manifests in experience.

Moreover, if you notice—and this is the third instruction—that the sense desire is not present, wait a moment and it will arise. When it’s not present, notice how the wanting emerges, gradually or suddenly, and becomes present. The very first time you notice some particular form of wanting or of sense desire, you are watching it arise in your phenomenal field.

The fourth movement in this exploration of the nuanced texture of sense desire is to be aware of the experience of abandoning it. Remember, the hindrances are obstacles to concentration. Sense desire is an obstacle to understanding and to insight. It’s not that we are trying to beat it up or suppress it or deny it, but we are trying to become aware of it. Once you notice that this very basic impulse to want things has arisen, notice how your experience changes when you decide to let go of it. The bringing of a gentle intention of letting go, to that very particular experience of sense desire, is also something that can be observed with focused awareness.

And fifthly, to take it a step farther, notice what attitude you can take, what intentional stance you can manifest, in a moment of awareness that will contribute to the non-arising of that particular sense desire. Remember, we’re not working with generalities here. It’s not about desire in general.

Insight meditation, vipassanā meditation, the foundations of mindfulness practice, are all about the details: becoming aware of this instantaneous manifestation of this particular desire for this very specific sense object.

And by the time you get through noticing all that, it’s gone and the next one is there. As we develop and hone our ability to see ever more closely what’s happening, we see more and more of these episodes of awareness arising and passing away.

To recapitulate, we are being asked to work with the hindrance of sense desire in five different ways. Notice the sense desire when it is there; notice when it is not there; notice as it arises; once it’s arisen, notice the texture of the intention to abandon it. The arisen sense desire does not have to rule our experience—we can let go of it. And then once we’ve let go of it, notice how we can cultivate an attitude that will contribute to its non-arising in the next moment of experience.

I think it is these last two moves that make this practice transformative. The Buddha directs us to pay attention to unwholesome mental objects, not to reinforce them but to undermine their hold on the mind. The hindrances cannot survive the bright light of awareness. As mindfulness grows, mental capacity is gradually shifted from the objects of attention to the process of being aware. This requires an attitude of letting go of the object, of abandoning attachment to it. The mind is a dynamic process; mental objects, as snapshots frozen in moments of time, are inherently static. When the mind is stuck on what has arisen, it is rigid and limited; but the mind that is letting go—moment after moment—keeps open to the emerging flow. This text is training us at a microcosmic mental level to step lightly in the field of phenomena, and to constantly explore the very cutting edge of experience.

This text is training us to step lightly in the field of phenomena, and to explore the very cutting edge of experience.

All this, and we have so far only covered the first five of the 108 mental objects. The same five experiential movements are applied to each of the remaining four hindrances, and then somewhat different strategies of selective attention, nevertheless working at the same detailed scale, are introduced to guide us through other territory of the inner landscape: aggregates, sense spheres, factors of awakening and noble truths. Shall we proceed…?

THE FOURTH FOUNDATION OF MINDFULNESS

So how does a person abide observing mind objects as mind objects? Here a person abides observing mind objects as mind objects in terms of:

The Five Hindrances (25)

- When there is sense desire in him, a person is aware: ‘There is sense desire in me’;

- or when there is no sense desire in him, he is aware: ‘There is no sense desire in me’;

- & when the arising of unarisen sense desire occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the abandoning of arisen sense desire occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the future non-arising of abandoned sense desire occurs, he is aware of that.

- When there is aversion in him, he is aware: ‘There is aversion in me’;

- or when there is no aversion in him, he is aware: ‘There is no aversion in me’;

- & when the arising of unarisen aversion occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the abandoning of arisen aversion occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the future non-arising of abandoned aversion occurs, he is aware of that.

- When there is sloth & torpor in him, he is aware: ‘There is sloth & torpor in me’;

- or when there is no sloth & torpor in him, he is aware: ‘There is no sloth & torpor in me’;

- & when the arising of unarisen sloth & torpor occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the abandoning of arisen sloth & torpor occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the future non-arising of abandoned sloth & torpor occurs, he is aware of that.

- When there is restlessness & remorse in him, he is aware: ‘There is restlessness & remorse’

- or when there is no restlessness & remorse in him, he is aware: ‘There is no restlessness & remorse in me’;

- & when the arising of unarisen restlessness & remorse occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the abandoning of arisen restlessness & remorse occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the future non-arising of abandoned restlessness & remorse occurs, he is aware of that.

- When there is doubt in him, he is aware: ‘There is doubt in me’;

- or when there is no doubt in him, he is aware: ‘There is no doubt in me’;

- & when the arising of unarisen doubt occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the abandoning of arisen doubt occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the future non-arising of abandoned doubt occurs, he is aware of that..

The Five Aggregates (15)

A person is aware:

- Such is material form;

- such is its origin;

- such is its disappearance.

- Such is feeling;

- such is its origin;

- such is its disappearance.

- Such is perception;

- such is its origin;

- such is its disappearance.

- Such are formations;

- such is their origin;

- such is their disappearance

- Such is consciousness;

- such is its origin;

- such is its disappearance

The Six Bases (36)

- A person is aware of the eye;

- he is aware of forms;

- & the fetter that arises dependent on both, he is aware of that;

- & when the arising of the unarisen fetter occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the abandoning of the arisen fetter occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the future non-arising of the abandoned fetter occurs,

- he is aware of that.

- A person is aware of the ear;

- he is aware of sounds;

- & the fetter that arises dependent on both, he is aware of that;

- & when the arising of the unarisen fetter occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the abandoning of the arisen fetter occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the future non-arising of the abandoned fetter occurs,

- he is aware of that.

- A person is aware of the nose;

- he is aware of odors;

- & the fetter that arises dependent on both, he is aware of that;

- & when the arising of the unarisen fetter occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the abandoning of the arisen fetter occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the future non-arising of the abandoned fetter occurs,

- he is aware of that.

- A person is aware of the tongue;

- he is aware of flavors;

- & the fetter that arises dependent on both, he is aware of that;

- & when the arising of the unarisen fetter occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the abandoning of the arisen fetter occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the future non-arising of the abandoned fetter occurs,

- he is aware of that.

- A person is aware of the body;

- he is aware of touches;

- & the fetter that arises dependent on both, he is aware of that;

- & when the arising of the unarisen fetter occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the abandoning of the arisen fetter occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the future non-arising of the abandoned fetter occurs,

- he is aware of that.

- A person is aware of the mind;

- he is aware of mind objects;

- & the fetter that arises dependent on both, he is aware of that;

- & when the arising of the unarisen fetter occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the abandoning of the arisen fetter occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the future non-arising of the abandoned fetter occurs,

- he is aware of that

MINDFULNESS OF 108 MENTAL OBJECTS

The Seven Awakening Factors (28)

- When there is the mindfulness awakening factor in him, a person is aware: ‘There is the mindfulness awakening factor in me’;

- or when there is no mindfulness awakening factor in him, he is aware: ‘There is no mindfulness awakening factor in me’;

- & when the arising of the unarisen mindfulness awakening factor occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the coming to fulfilment by development of the arisen mindfulness awakening factor occurs, he is aware of that.

- When there is the investigation-of-states awakening factor in him, he is aware: ‘There is the investigation-of-states awakening factor in me’;

- or when there is no investigation-of-states awakening factor in him, he is aware: ‘There is no investigation-of-states awakening factor in me’;

- & when the arising of the unarisen investigation-of-states awakening factor occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the coming to fulfilment by development of the arisen investigation-of-states awakening factor occurs, he is aware of that.

- When there is the energy awakening factor in him, he is aware: ‘There is the energy awakening factor in me’;

- or when there is no energy awakening factor in him, he is aware: ‘There is no energy awakening factor in me’;

- & when the arising of the unarisen energy awakening factor occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the coming to fulfilment by development of the arisen energy awakening factor occurs, he is aware of that.

- When there is the joy awakening factor in him, he is aware: ‘There is the rapture awakening factor in me’;

- or when there is no joy awakening factor in him, he is aware: ‘There is no rapture awakening factor in me’;

- & when the arising of the unarisen joy awakening factor occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the coming to fulfilment by development of the arisen joy awakening factor occurs, he is aware of

- When there is the tranquility awakening factor in him, he is aware: ‘There is the tranquility awakening factor in me’;

- or when there is no tranquility awakening factor in him, he is aware: ‘There is no tranquility awakening factor in me’;

- & when the arising of the unarisen tranquility awakening factor occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the coming to fulfilment by development of the arisen tranquility awakening factor occurs, he is aware of that.

- When there is the concentration awakening factor in him, he is aware: ‘There is the concentration awakening factor in me’;

- or when there is no concentration awakening factor in him, he is aware: ‘There is no concentration awakening factor in me’;

- & when the arising of the unarisen concentration awakening factor occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the coming to fulfilment by development of the arisen concentration awakening factor occurs, he is aware of that.

- When there is the equanimity enlightenment factor in him, he is aware: ‘There is the equanimity awakening factor in me’;

- or when there is no equanimity enlightenment factor in him, he is aware: ‘There is no equanimity awakening factor in me’;

- & when the arising of the unarisen equanimity enlightenment factor occurs, he is aware of that;

- & when the coming to fulfilment by development of the arisen equanimity awakening factor occurs, he is aware of that.

The Four Noble Truths (4)

- A person is aware as it actually is: ‘This is suffering’;

- he is aware as it actually is: ‘This is the origin of suffering’;

- he is aware as it actually is: ‘This is the cessation of suffering’;

- he is aware as it actually is: ‘This is the way leading to the cessation of suffering.’

Such is the way he abides observing mind objects as mind-objects internally,…or externally,…or both.

Or he abides observing among mind objects: arising mind objects…vanishing mind objects…or both.

Or else mindfulness becomes established for him just to know, just to be mindful: ‘there is a mind object’.

And he abides independent, not clinging to anything in the world.

NOTE: The word “monk” (bhikkhu) has been replaced with “person” throughout, but the masculine gender has been retained.