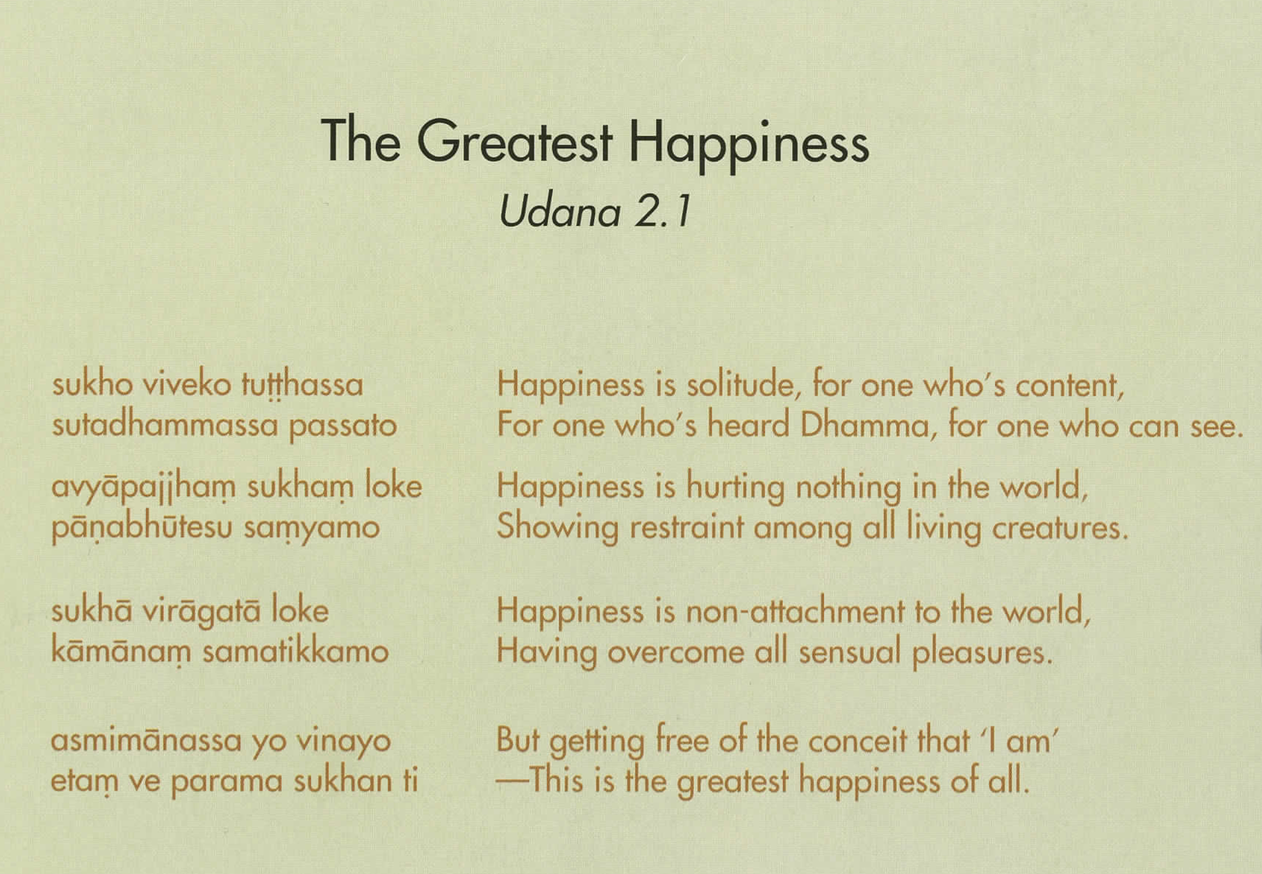

These verses are said to have been uttered very soon after the Buddha’s awakening to Mucalinda, the Nāga (Serpent) King, after he coiled seven times around his body and spread his hooded head to protect the Awakened One from rain. This mythical imagery aside, the poem offers a cogent definition of happiness at four different, gradually intensifying, levels of scale.

The ascetic monk finds happiness in dwelling alone in the forest, far from the web of social responsibility, immersed in nature, and no longer hankering for the alluring things of the world. Such contentment is aided by having heard the Dhamma, the teachings of the Buddha, which praises the value of being content with very little.

When this simple lifestyle is further augmented by a deep commitment to ethical restraint, non-violence, and an attitude of loving care toward all living beings, the happiness deepens to encompass the heart. The experience of kindness itself, as a wholesome mental state, is a source of great joy and well-being.

Even greater levels of happiness are accessed by fundamentally uprooting the primal compulsions of desire: the urge to acquire, consume, or grasp what is gratifying; and the impulse to ignore, reject or destroy what is regarded as hateful. The overcoming of this craving constitutes the cessation of suffering.

The last and final obstacle to the highest happiness of all is the unconscious reflex of concocting a view of self that stands at the center of all that one thinks, says, and does. The Buddha here describes, no doubt for the first time, the experience of insight that stands as the culmination of the ascetic path and is the unique defining feature of his teaching.