This story combines recollections from several people on the 2010 BCBS pilgrimage. Contributing were Helen Rosen, Steve McKay, Jim Dailey, Justin Kelley, Victor Bradford, Jeane van Gemert, Mu Soeng, Indira Maini, Edith Haenel, Kristy Arbon, Catherine Brousseau, Emily Carpenter, Amita Chopra and Jaylene Summers.

In February 2010, twenty BCBS pilgrims set out to see Siddhartha’s stomping grounds, to walk and sit where he did 2,500 years ago. We found them in twenty-first century India, an intense setting that insisted on becoming foreground rather than background. In the countryside, all arable land seemed to be under cultivation. The farms looked productive and well-tended, and it appeared that life in the farm villages may have changed little for thousands of years. The cities and towns had a different feeling. The population density was striking, with streets that were narrow, congested and teeming with people. The cities all seemed environmentally blighted, with polluted air and water, no noticeable sewage or trash disposal. At the same time most of the people we encountered were civil, with some apparent sense of order in their lives, and some joy, especially in the children we saw. It made me think about the connection between happiness and the material conditions of life; many people were living with apparent equanimity in conditions in which we would be miserable. It made the point that our view of things determines how we feel about them. But I also wondered whether, for almost anyone, there is suffering when poverty becomes destitution, or when environmental blight affects one’s senses all the time.

Getting a physical feel for the geography of the Buddha’s meanderings was a huge bonus of this pilgrimage. Most of the suttas locate precisely where a discourse of the Buddha took place: the region, the forest, the park. Tradition has it that the suttas were memorized by the Buddha’s assistant, Ānanda. When the Sangha met soon after the Buddha’s Parinibbāna, Ānanda identified the location of each teaching to verify them in the memory of others, and to anchor each discourse in time and space.

Would we be sight-seeing or site-being?

Delhi

The group of BCBS pilgrims gathered at the World Buddhist Center on a warm winter’s day in New Delhi. We listed our intentions and shared them together. One of mine was “to appreciate with gratitude all experiences.” Mu Soeng invited us to reflect on how we were constructing our reality of becoming a “pilgrim.”

Would we be sight-seeing or site-being? We were challenged to look at our intentions closely, to see how we consume through “I, me, mine,” constructing and reifying our personal stories. I became uncomfortably aware of the story of “my pilgrimage” to India but I was eager and restless to begin. I took to heart a commitment to be with the experiences of the trip with “don’t know” mind, to connect with the larger global community of Buddhist practitioners, to let in whatever inspirations arose from the journey, and to practice letting go. Suffering, I knew, would be a major theme on this pilgrimage. I anticipated my time in India would be quite a low-key experience of being with what was—my suffering and the suffering I saw. I anticipated seeing fellow human beings doing what human beings do, including what we do when we appreciate a man like Shakyamuni Buddha.

While in New Delhi, we visited the site where M. K. Gandhi was assassinated. At Birla House, the home of a prominent businessman supporter where he was staying as a guest, we entered his room as it was at the time of his assassination. Framed on the wall were Gandhi’s possessions at the time of his death—perhaps ten or twelve items, mostly eating utensils, his glasses, and a walking stick. I was very moved by this simplicity. I stood there and made a solemn commitment to shed some of my many possessions.

“Live simply so that others may simply live. “

– M.K. Gandhi (1869-1948)

Varanasi

“The Exposition of the Truths” (MN141) begins: “Thus have I heard. On one occasion the Blessed One was living at Benares in the Deer Park at Isipatana.”

Benares is Varanasi on modern maps. It is famous for silk production and for the ghats along the Ganges where people bathe in the sacred waters and pour in the ashes of their dead. A few miles away is the Deer Park at Sarnath (another name for Isipatana), where the Buddha gave his first teaching of the Dhamma. A forest in the Buddha’s time, it is now a serene fenced park with lawns and paths, great trees where meditators sit, and ruins of the many monasteries built there over the centuries. Toward the back is a tall, massive brick stupa, which pilgrims quietly circumambulate. We did this as well, and then found a quiet spot to sit. We reflected on the Four Noble Truths. To imagine these first teachings being offered here so many years ago was humbling. In reflecting on the teachings of the Four Noble Truths, I imagined the radiant, newly awakened Buddha arriving and offering his path to freedom here.

We felt a surprisingly gentle vibe, the sort that geography can seem wrapped in after thousands of years of visiting beings’ sacred intentions.

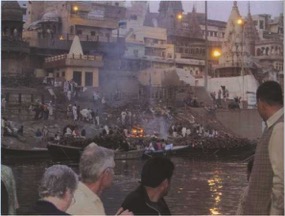

We bussed back to Varanasi where the group boarded bicycle rickshaws for a dusty, perilous ride through the zany, traffic-choked streets to the Ganges River ghats. There, we boarded a boat, rowed by two men, and viewed the Hindu cremation ceremonies that continue all day, every day. Death is never very far away in India. The Buddha’s Five Reflections on old age, sickness, and death came to mind: “I am of the nature to die, I have not gone beyond death.” At sunset we sat in the boat, watching families put the bodies of their loved ones onto funeral pyres and commit the ashes to the river.

Bodhgaya

After visiting the Alice Project—a privately run school focusing on educating children holistically—we departed Varanasi for Bodhgaya, a six-hour bus ride away. I was envisioning another quiet holy space visited by pilgrims, the scene of Buddha’s enlightenment. Instead, it was a scene of pandemonium, with a shopping mall on the cobblestones. Many monks and pilgrims milled around under prayer flags as we walked toward the Mahabodhi Temple. It was around nine in the evening, closing time. In the darkening evening there was urgency in the group’s pace that matched the sound and fury around us. But as I turned the corner, my first view of the Mahabodhi Temple, fifty-five meters high, made me stop abruptly. The magnificent building, festooned with a thousand butter lamps, caused me to pause as the street party atmosphere faded away. It was my most sacred moment in Bodhgaya.

The next morning we walked to Mahabodhi Temple again for a morning meditation under the Bodhi Tree (or perhaps, relative of same) where Buddha was enlightened. We joined hundreds of worshipers chanting, prostrating, circumambulating, meditating, along with sight-seers (and site-seers), tourists, monks of various orders, beggars of all ages, hawkers of various wares, money changers, pick pockets and other opportunists, crowding the walkways all along the temple grounds, inside and out. More like a carnival than a sacred ground, it was a long way from the tranquility and serenity one may have imagined surrounding the holy site of the Buddha’s awakening. For sure, all is impermanent. Yet, through the noise and ceaseless activity, we felt a surprisingly gentle vibe: the sort of vibe geography can seem wrapped in after thousands of years of visiting beings’ sacred intentions.

After our meditation, Mu Soeng invited us to consider the nature of enlightenment: awakening to reality as a process; dependent origination; a deeply compassionate transformation. We sat apart from the jostling, chanting, perambulating, prostrating crowds and tried to concentrate. Were we consumers, seeking to acquire enlightenment?

Later, I sat down beside a Tibetan monk who was rapidly chanting a mantra and bowing. Dozens of people were passing by and the environment, by now, seemed quite peaceful. Suddenly, the unmistakable tone of a cell phone—that modern symbol of irreverence— went off. Even here, I thought, watching attachment to the “perfect” experience fade away. I noticed a few people looking around, and then I noticed the chanting monk reach into his robes. The chanting stopped, followed by, “Hello? Hello?” The monk carried on a very animated and uninhibited conversation for a few minutes, with several laughs. Then I heard, “Goodbye, goodbye.” The monk placed the phone back in his robes and, without skipping a beat, continued on with his chant.

Later, I sat down beside a Tibetan monk who was rapidly chanting a mantra and bowing. Dozens of people were passing by and the environment, by now, seemed quite peaceful. Suddenly, the unmistakable tone of a cell phone—that modern symbol of irreverence— went off. Even here, I thought, watching attachment to the “perfect” experience fade away. I noticed a few people looking around, and then I noticed the chanting monk reach into his robes. The chanting stopped, followed by, “Hello? Hello?” The monk carried on a very animated and uninhibited conversation for a few minutes, with several laughs. Then I heard, “Goodbye, goodbye.” The monk placed the phone back in his robes and, without skipping a beat, continued on with his chant.

We visited the Mahakala cave which was dark and small, where Shakyamuni’s ascetic practice took place. It was a couple hundred feet up the side of a craggy mountain, treeless and littered with debris. Unlike the walk the Buddha-to-be took, the road up to the cave was roughly paved with concrete to accommodate tourists, and, as with the other pilgrimage sites, the walk was lined with beggars of all ages and all degrees of affliction. Poverty is a pathetic situation.

Equanimity is helpful when considering, on the one hand, what may be referred to as the sacredness of these sites, and on the other, the graffiti-scrawled rocks and garbage.

The teaching of the Middle Way was very clear here as I stood on the mountainside and looked out on the broad expanse of the Ganges plain below. The statue of the emaciated Buddha in the cave reminded me of his description of his practice during that time in the Mahāsaccaka Sutta: “I beat down, constrained, and crushed mind with mind. While I did so, sweat ran from my armpits.” It was inspiring to reflect on the amount of effort the Buddha put into his spiritual quest, and even more inspiring that he resolved that such iron-fisted determination was not the way. Instead, the path to awakening called for a balance between ease and effort. I reflected on my own life and on the ways with which I have applied iron-fisted determination in my practice, only to discover, often through the patient guidance of dharma teachers, that insight arises most naturally when there is a balance between the extremes of effort and ease.

The teaching of the Middle Way was very clear here as I stood on the mountainside and looked out on the broad expanse of the Ganges plain below. The statue of the emaciated Buddha in the cave reminded me of his description of his practice during that time in the Mahāsaccaka Sutta: “I beat down, constrained, and crushed mind with mind. While I did so, sweat ran from my armpits.” It was inspiring to reflect on the amount of effort the Buddha put into his spiritual quest, and even more inspiring that he resolved that such iron-fisted determination was not the way. Instead, the path to awakening called for a balance between ease and effort. I reflected on my own life and on the ways with which I have applied iron-fisted determination in my practice, only to discover, often through the patient guidance of dharma teachers, that insight arises most naturally when there is a balance between the extremes of effort and ease.

Rajgir

At Rajgir, Mu Soeng’s reflection on compassion and how it arises spontaneously out of sadness touched me with a previously unarticulated awareness. I imagined how I would want to be treated if I were one of the many beggar women pleading for food or money for my child. Tears came to my eyes and a door of compassion opened in my heart.

The Simile of the Heartwood (MN29) begins: “Thus have I heard. On one occasion the Blessed One was living at Rajagaha on the mountain Vulture’s Peak.”

Vultures Peak, in modern Rajgir, is where the Buddha and senior monks went to meditate, away from the monastery and the villagers. Vulture’s Peak is in a range of low mountainous outcroppings full of crags and caves. Today, a long paved walk up the mountain passes the holy caves, marked by candle stubs, prayer flags, and gold patches left by pilgrims. Historically this was the site of many dhamma talks, rains retreats, and an assassination attempt by Devadatta. A measure of equanimity is helpful when considering, on one hand, what may be referred to as the sacredness of these sites where the Buddha walked and talked, and, on the other, the graffiti-scrawled rocks and garbage-strewn walkways that degrade the area. Just this, just now.

An excerpt from a description of Nalanda University at the front entrance reads: “Aware of the smallness of human life, and the greatness of its potential.” We spent a day at Nalanda museum and university site. Guides informed us that Nalanda University lasted for a thousand years, and has been in ruins for twelve hundred years. My mind constructed how wonderful it might have been to be one of three thousand monks or one of seven thousand students chosen to attend the great university in those early centuries when education was a rare privilege.

We left Rajgir for Patna. Our bus was suddenly held up by a fatal road accident. A truck had hit a girl and her life force had left her body. Justin Kelley, one of our group leaders, made an announcement to the group that we would be held up because of the accident and that we might like to send mettā to the dead person and their living loved ones. Tears came to my eyes as I thought of the suffering that would result from the accident. I remembered my own grief over loved ones lost, and knew that what I experienced was about to be a very fresh and very raw experience for someone else. I reflected on the universality of suffering that comes from the death of a loved one. No-one can escape it, be they rich or poor. It’s a shared experience. Even if in the States we cannot relate to the everyday suffering of the millions of poverty-stricken Indians, we can surely relate to the suffering around death. It’s the great leveler—the homogenizing influence that reminds us all of the reality of existence.

We left Rajgir for Patna. Our bus was suddenly held up by a fatal road accident. A truck had hit a girl and her life force had left her body. Justin Kelley, one of our group leaders, made an announcement to the group that we would be held up because of the accident and that we might like to send mettā to the dead person and their living loved ones. Tears came to my eyes as I thought of the suffering that would result from the accident. I remembered my own grief over loved ones lost, and knew that what I experienced was about to be a very fresh and very raw experience for someone else. I reflected on the universality of suffering that comes from the death of a loved one. No-one can escape it, be they rich or poor. It’s a shared experience. Even if in the States we cannot relate to the everyday suffering of the millions of poverty-stricken Indians, we can surely relate to the suffering around death. It’s the great leveler—the homogenizing influence that reminds us all of the reality of existence.

The thousand-year-old golden statue of the reclining Buddha gently evoked a contemplation of the impermanence of life.

Kushinagar

At Kushinagar, where the Buddha died, we meditated outside the Mahāparinibbāna Stupa in the hushed mist of early morning. Inside, the thousand-year-old golden statue of the reclining Buddha, facing west, gently evoked a contemplation of the impermanence of life. Life felt like a “bubble on a stream or a cloud in the summer sky.”

Later we walked to the “Dispute Tree” (or a relative of same) where eight tribes evenly distributed the Buddha’s relics, avoiding an unseemly confrontation. Tall and wide, the tree offers its shade to surrounding paddy fields.

We crossed the border to travel to Lumbini, Nepal, the Buddha’s birthplace. Scenes along the route included a man gently and lovingly petting one of his lambs; a cow trotting anxiously to and fro, nearly running into a schoolboy who deftly sidestepped to safety; paunchy men seeming idle and aimless; slender women purposefully carrying children, or bags, or loads of wood; laundry drying on clotheslines in hamlets, on rooftops, between huts and shanties, beside the chimneys of brick kilns; dark, derelict-looking buildings with occupants; open-doored schools, filled with uniformed children; our bus coming to full stop for a meandering puppy.

We departed Kushinagar, the place of the Buddha’s death, at nine in the morning then arrived in Lumbini, the place of the Buddha’s birth, at six that evening. The significance of having been in both of these holy places on the same day brought pause, contemplation, and appreciation.

Lumbini

Ānanda, this place is where the Tathāgata was born, this is a place, which should be visited and seen by a person of devotion and which would cause awareness and apprehension of the nature of impermanence. (Mahāparinibbāna Sutta, DN16).

We sat on the grounds of the sacred garden and stupa at Mahamaya Temple (named for the Buddha’s mother). I listened to the fluttering of the Tibetan prayer flags strung across the trees outside the temple as we sat meditating. A wave of sadness swept over me. I had a lump in my throat and my eyes stung with tears—I had to move away from the group very quietly after we got up from meditation to find a quiet spot to deal with this intense emotion. I don’t know why I felt that way. Justin had told me that India can bring out some intense emotions.

Many centuries after the Buddha, we are fortunate to be able to traverse the same path and seek an end to suffering.

The Venerable Sayadaw U Pandita, assisted by his translator, the Venerable Vivekananda, welcomed us to his retreat center in Lumbini. His basic robes, worn in the same style as the Buddha, represented the way he lives his life: dedicated whole-heartedly to the vinaya of a traditional Buddhist monastic. As we sat in audience with him in an ornate room at Panditarama, he spoke of the difficulties we face today, bombarded by sensory stimuli from all angles, and how the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta was a supreme teaching, encompassing the entire path. He wasted not a single action, not a single movement. All that he did and said was purposeful. Sitting in this wise, old being’s presence made us feel calm and safe.

The Venerable Sayadaw U Pandita, assisted by his translator, the Venerable Vivekananda, welcomed us to his retreat center in Lumbini. His basic robes, worn in the same style as the Buddha, represented the way he lives his life: dedicated whole-heartedly to the vinaya of a traditional Buddhist monastic. As we sat in audience with him in an ornate room at Panditarama, he spoke of the difficulties we face today, bombarded by sensory stimuli from all angles, and how the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta was a supreme teaching, encompassing the entire path. He wasted not a single action, not a single movement. All that he did and said was purposeful. Sitting in this wise, old being’s presence made us feel calm and safe.

Kapilavastu

I was enveloped with sadness again, at Kapilavastu, as we sat and meditated near the East gate, from which the Buddha walked out of a life of luxury and wealth to seek a greater truth—a way to end suffering. Now, many centuries later, we are fortunate to be able to traverse the same path and confront our own vulnerabilities and seek an end to our suffering. We meditated on the gravity of his decision at that place, as children called out to us from the boundary wall and loud vehicles raced along the road.

Sravasti

Two Kinds of Thought (MN 19) begins: “Thus have I heard. On one occasion the Blessed One was living at Sāvatthī in Jeta’s Grove, Anāthapiṇḍika’s Park.”

Sravasti is barely on the map in northeastern Uttar Pradesh in India. More recorded suttas were delivered here than from any other place, because the Buddha established a large monastery and spent twenty-four rains retreats at Sravasti. Jeta’s Grove is now a large, walled park, containing gardens, sloping lawns, old groves, and the ruins of many temples, monasteries, and stupas.

Three ruins mark where the Buddha meditated, slept, and received guests. Here we saw monks of various Buddhist traditions and groups of pilgrims from several countries, some chanting, some meditating, and some exploring. Anāthapiṇḍika’s bodhi tree may or may not be from a sapling of the original in Bodhgaya, but it is cared for as if it were. Steel beams support the larger limbs in an effort to keep them from crashing down as age, pollution, and drought take their toll.

My favorite memories of the pilgrimage came at the very beginning and the very end, during our collective meditation sessions. We began at Sarnath, and ended at Anāthapiṇḍika’s Park. Mu Soeng began each session by setting a theme. Among these themes was that our life is what matters, not just the apparent quality of our meditation sessions. Meditation is a rudder, which is critical, and skillfully knowing how and where to guide ourselves is even more critical, but these skills are to be integrated with the entire system in a gentle and compassionate manner. Our meditation experiences throughout the pilgrimage were irreplaceable, but somehow the initial “beginner’s mind” experience, and the last “we can rejoice in a well-lived accomplishment” experience, now seem especially valuable.

My favorite memories of the pilgrimage came at the very beginning and the very end, during our collective meditation sessions. We began at Sarnath, and ended at Anāthapiṇḍika’s Park. Mu Soeng began each session by setting a theme. Among these themes was that our life is what matters, not just the apparent quality of our meditation sessions. Meditation is a rudder, which is critical, and skillfully knowing how and where to guide ourselves is even more critical, but these skills are to be integrated with the entire system in a gentle and compassionate manner. Our meditation experiences throughout the pilgrimage were irreplaceable, but somehow the initial “beginner’s mind” experience, and the last “we can rejoice in a well-lived accomplishment” experience, now seem especially valuable.

The meaning of Dhamma became real in a way we never could appreciate by just reading about it in scholarly works.

The meaning of Buddha and how he lived his life became real by following his footsteps through India and Nepal. At the end of the trip I felt that I had been on a long journey with him. He had moved from the realm of mythology to history and we were the beneficiaries of his revelations. Feeling the same ground under our feet, looking out over the same mountains, rivers and lush fields took me back through the corridors of time and helped me imagine what he felt. It’s not often that one visits sites where some of humanity’s major accomplishments took place, and their presence and Mu Soeng’s interpretations of them changed my practice. The Buddha’s dwellings became a tangible part of my life and memories. This was a grand opportunity to visit the places where one of history’s most remarkable people made some of the greatest contributions to human civilization, but also to realize we need to carry these places in our hearts and minds far more than on a map.

The meaning of Dhamma became real in a way we never could appreciate by just reading about it in scholarly works. Being in the same environment, feeling the power of meditating together and then revisiting the Buddha’s teachings in the same places they were first given and discussed by scholars: how better to know what Dhamma means! But most lingering of all, when I pick up the scriptures and read the opening lines of a sutta, an image, a feeling, a memory arises that makes the teachings of the Blessed One tangible, immediate, and alive.

“This is the entire holy life, Ānanda, that is good friendship, good companionship, good comradeship.” SN 45.2

The most surprising and important aspect of the trip for me was the group itself. The formation of a sangha during our bus trip seemed to be the most visible gift we all gave to each other. Mu Soeng commented that the group was “mature,” and not only in years. I was impressed and inspired by the way many members of the group earnestly sought to adhere to sīla, practicing right speech and action, kindness and compassion. Our travels had their rigors—long train and bus rides, unexpected delays and changes, a number of people developing colds and other ailments—but a sense of equanimity and acceptance prevailed. It was a mobile sangha, a spiritual child emerging from our shared interests, ideals and practices, a thing that is no “thing,” but great and memorable nonetheless.

The most surprising and important aspect of the trip for me was the group itself. The formation of a sangha during our bus trip seemed to be the most visible gift we all gave to each other. Mu Soeng commented that the group was “mature,” and not only in years. I was impressed and inspired by the way many members of the group earnestly sought to adhere to sīla, practicing right speech and action, kindness and compassion. Our travels had their rigors—long train and bus rides, unexpected delays and changes, a number of people developing colds and other ailments—but a sense of equanimity and acceptance prevailed. It was a mobile sangha, a spiritual child emerging from our shared interests, ideals and practices, a thing that is no “thing,” but great and memorable nonetheless.

Return to the land of the devas

I returned to the land of the devas (a term for the US that caught on during the pilgrimage) with mind-stimulated happiness, pleasant vedanā, and gratitude for a unique trip. I felt like everything had changed. My whole being felt different. I felt more attentive to my surroundings and the people around me and the notion of anicca seemed to have penetrated every cell.

Some days I am back in India, in my mind. In the US, the streets may be cleaner, but they seem a bit meaner—noticeably more efficient, neurotic, and urgent. But maybe that’s just me. At least people aren’t asking me as directly for money, although the advertising industry sure seems at least as persistent as any beggars I encountered. Looking back on it, all those subtly-conditioned thoughts which pop in and out of my head like virtual particles, demanding attention and “payment,” remind me of the beggars. Well, it’s fine to be back but I am glad there are places like the Buddhist sites in our hearts. Keep sitting—the world will benefit.

Kristy Arbon, Center Manager at BCBS since 2008, was a freelance writer for an environmental website. She began meditating in the Tibetan tradition in Australia in 1988 and has practiced in the Theravadan tradition since moving to the U.S.