Jay L. Garfield is the Doris Silbert Professor in the Humanities and Professor of Philosophy, Logic and Buddhist Studies at Smith College. He chairs the Philosophy department and directs Smith’s logic and Buddhist studies programs as well as the Five College Tibetan Studies in India program. He is also visiting professor of Buddhist philosophy at Harvard Divinity School, professor of philosophy at Melbourne University, and adjunct professor of philosophy at the Central University of Tibetan Studies.

Jay L. Garfield is the Doris Silbert Professor in the Humanities and Professor of Philosophy, Logic and Buddhist Studies at Smith College. He chairs the Philosophy department and directs Smith’s logic and Buddhist studies programs as well as the Five College Tibetan Studies in India program. He is also visiting professor of Buddhist philosophy at Harvard Divinity School, professor of philosophy at Melbourne University, and adjunct professor of philosophy at the Central University of Tibetan Studies.

The following article explores questions and themes about Buddhist understandings of the person that Jay developed in more detail in his freely offered online course. To watch these recordings, click here. A pdf version of this article can be downloaded here.

One of the Buddha’s most important insights is found in the second of the four noble truths: that the suffering that pervades our existence is caused by attraction and aversion, which, in turn, are grounded in a primal confusion regarding the nature of reality. This means, as we learn in the third truth, that if we are to eliminate that suffering, we must eradicate that confusion. It is the root of cyclic existence. That is why, as becomes clear in the fourth truth, right view is so important. How we see the world matters a great deal. And this is why so much of Buddhist practice aims at changing the way we see the world.

There is one part of the world that it is especially important to see aright, and that is ourselves. And this, of course, is why so much Buddhist practice is devoted to developing deep insight into who and what we are. And, as anyone who has spent any time in Buddhist study or practice is aware, one of the most important insights to develop is that into selflessness. To understand who you are is to understand that you have no self.

That is easy to say, and hard to understand. It is also sometimes hard to see why this insight is so important. It requires some philosophical reflection. The great Tibetan scholar-practitioner Tsongkhapa (1357-1419) reminds us that if we want to convince ourself that something does not exist, we must first get a good grip on what that thing is whose existence we are rejecting. Otherwise, he argues, we might deny the wrong thing and so miss the point. Or we might deny too little, and continue to reify the object of negation. Or we might deny too much, and fall into a dangerous nihilism.

Tsongkhapa is following an idea articulated by the Indian Madhyamaka philosopher Candrakīrti (c. 600-650 CE), who in his treatise Introduction to the Middle Way (Madhyamakāvatāra) tells the story of a man who is afraid that a poisonous snake has taken up residence in one of the walls of his house. In order to alleviate his fear, the man searches the house for an elephant, and satisfies himself that there is none there. He then rests at ease.

Candrakīrti’s idea is that even once we recognize that a conception or a commitment is causing us problems, it is often easier and more tempting to confuse it with another idea, to refute that other idea, and to leave the problematic conception in place. This is particularly true when we suffer from an irresistible compulsion to adhere to the initial problematic commitment, despite the difficulties it raises. The serpent in this analogy is the self. Candrakīrti thinks that even a little philosophical reflection will convince us that there is something amiss in our thinking that we are selves. And he thinks that the ramifications of succumbing to the self illusion undermine any attempt to understand who and what we are, and are devastating to our moral lives.

I agree with Tsongkhapa and Candrakīrti. I think that the self illusion is deep and irresistible, and that it is pernicious, causing suffering and a distortion of our moral lives. I therefore agree that it is an important goal of practice to extirpate it, and that in order to do so, we must first be crystal clear about what that illusion is, and what it is to be liberated from it. That is, we must be clear about what we are denying when we deny that we are selves, and we must be clear that to deny that we are selves is not to deny that we exist.

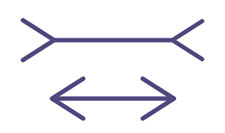

To navigate between the rejection of the self and the absurd and nihilistic view that we do not exist at all, it is useful to reflect on what an illusion is. Here, I follow the traditional Indian analysis of an illusion, which seems to get the matter just right. An illusion is something that exists in one way, but appears to exist in another. There are many examples used to illustrate this idea in Indian Buddhist texts. Perhaps the best known is the mirage: a mirage exists as a refraction pattern in the atmosphere, but appears to be water. I like the Müller-Lyer illusion as an illustration:

The two parallel lines are in fact equal in length, but appear to be unequal. Even when you measure them, or draw them yourself, and know that they are equal in length, they appear to be unequal. We are like that. We exist as persons, but appear to be selves. To understand no-self, and so to cultivate that insight in meditation, we must get clear about that distinction and about the consequences of failing to draw it.

Let’s begin with the self. I want to give you a feel for what it is to posit a self. I want to do that by inviting you to join me in a thought experiment. The experiment proceeds in two parts. First, think of somebody whose body you would like to inhabit, maybe for a long time, maybe only for a short while. I will tell you whose body I would like to have: Ussain Bolt’s (of a few years ago). I only want it for 9.6 seconds. I want to feel what it is like to run that fast. Now, in developing this desire, I do not want to be Ussain Bolt. Ussain Bolt has already achieved that, and it does me no good. I want to be me, Jay, with Ussain Bolt’s body, so that I can enjoy what Ussain Bolt experiences.

The very fact that I can formulate this desire or take this leap of the imagination shows me that, deep down, I do not consider myself to be identical to my body, but rather to be something that has this body, and that could in principle have another one.

Now for the second part: imagine somebody whose mind you would like to have, just for a little bit. Once again, whether this desire or act of imagination is coherent or not is beside the point. (I would love to have had Stephen Hawking’s mind for long enough to understand general relativity and quantum gravity, but once again, this is not a desire to be Stephen Hawking, but to be me, enjoying his mind.) When you develop this desire, you do not wish to become that other person. She or he is or was already that other person, and that does nothing for you. You want to be you, with his or her mind. And, just as in the case of the body, the very possibility of formulating this desire, or imagining this situation shows that you do not consider yourself to be your mind, but rather to be something that has that mind.

The point of these exercises is to identify what we mean when we talk about a self. The very fact that you were able to follow me in this thought experiment shows that, at least before you think hard about it, you take yourself to be distinct from both your mind and your body, to be the thing that has your mind and your body, but that, without losing its identity, could take on another mind, another body, just like changing your clothes. When we say that there is no self, we are denying that anything like this exists.

Perhaps the best-known argument from Buddhist literature against the existence of the self is that found in The Questions of King Milinda (Milindapañha). The discussion begins with the King asking the apparently innocent question, “who are you?” Nāgasena replies coyly that he is really nobody; that he is called Nāgasena, but that this is just a name, a designation, and there is nothing to which it really refers. The name Nāgasena refers not to his body, his mind, his experiences, nor to anything apart from these.

The King replies that it seems to follow that there is nobody to whom to offer alms, nobody who wears the robe, nobody talking to him, and even nobody denying that he has a self. So, the King concludes, there must be something to which the name Nāgasena refers, something that presumably constitutes his self.

Nāgasena asks the King to consider the chariot on which he rode to the site of the dialogue. The King grants that he did ride a chariot, and so that the chariot he rode exists. But what, Nāgasena asks, is that chariot, really? He points out that the chariot is neither identical to its wheels, nor to its axles, nor to its poles, etc.… It cannot, he argues, be identical to any of its parts, for that would be to leave some others out; to select one part as the real chariot would be arbitrary, as well as clearly false.

One might be tempted to reply at this point that while the chariot is obviously not identical to any one of its parts, or even any proper subset of its parts, it is to be identified with all of its parts taken together. But Nāgasena immediately points out to the King that the chariot cannot simply be the sum of those pieces. After all, a pile of chariot pieces on the ground, delivered fresh from the chariot factory but not yet assembled, is not yet a chariot And it can’t even be identical to all of those parts suitably arranged or put together. If it were, then if we changed one of those parts, or changed their arrangement, we would have a different chariot. But that can’t be right. We could replace a wheel or an axle, and we would still have the same chariot, saying truly, “I have owned this chariot for years; all I need to do is to replace the wheels every so often,” or, “hey! I just got a new seat for my chariot. Come check it out.”

Nor is the chariot something different from those parts. After all, no chariot as the bearer of those parts remains when they are all removed. For this reason, we ought to resist the temptation to think of it as a separate entity that possesses those parts (just as we saw we should resist the temptation to think of ourselves as possessors of bodies and minds). Nor can we think of it as some mysterious entity located in the parts, but identical with none of them. Nobody takes that possibility seriously. So, Nāgasena argues, the words “the king’s chariot,” are merely a designation with no determinate referent.

But this is not an argument against the existence of the chariot. After all, we began by granting its reality. Instead, it does not exist as some singular entity that is either identical to or distinct from its parts. Its mode of existence is merely conventional, determined by our customs regarding the application of words like this chariot.

And this, Nāgasena instructs the King, is how we should think of the person who is called “Nāgasena” and his relation to that name. He is no singular entity. He is neither identical to nor distinct from his parts. He is not the possessor of those parts. There is no single part with which he is identical. His existence is merely nominal. A final account of the basic constituents of the world, even were it to contain his hair, fingers, desires, and experiences, contains no Nāgasena. The self to which the King, as well as the reader of the dialogue, might have thought that the name “Nāgasena” refers is therefore nowhere in the picture. But note that in presenting the analogy of the chariot, we never drew the conclusion that the chariot does not exist, or that it was incapable of bearing the King to the site of the debate. Likewise, we have not questioned whether Nāgasena exists, but only his mode of existence. His mode of existence is distinct from his mode of appearance; the appearance of the self is an illusion.

What, we might ask, is the status of the person who is no self? In particular, one might wonder, what accounts for the continuity of consciousness from one moment to the next, and the persistence of our identity through all of the changes we undergo in our lives if there is no self? Wouldn’t we exist even if there were no conventions? Isn’t our existence the precondition of any conventions? That is, we might ask, what exactly is the mode of existence that we in fact enjoy?

Nāgasena asks the King to reflect on the lamps that are lit in the evening. These small clay lamps then in common use in India did not contain enough oil to last through the night. The practice was to use a nearly depleted lamp to light the next lamp, and so on until daybreak, just as a chain smoker lights the next cigarette using the butt of the previous one.

Now, Nāgasena asks, consider the flame by one’s bed that was lit at dusk last night, and the flame to which one awakes this morning. Are they the same, or are they different? Should we say that there was a single flame that burned all night and was transferred from lamp to lamp, or should we say that a sequence of different flames burned through the night, each giving rise to the next? In one obvious sense, the flame of last night and the flame of this morning are different from one another: different oil is being consumed; they are burning on distinct clay lamps. But in another equally obvious sense, they are the same: they are each stages of a single causal continuum, an uninterrupted sequence of illumination by florescent gas.

It seems like the right thing to say is that the identity and continuity of the flame are constituted in part by causal continuity, in part by common function, but in the end primarily by the fact that we have a convention of talking that way. That is, we conventionally ascribe identity to the elements of such causal sequences, and not to sequences of events that are less causally connected, such as the sequence of lamps in the other room.

This is how The Questions of King Milinda invites us to think of our own personal identity. Just as there is no drop of oil or bit of incandescent gas that remains constant in the lamp from evening to morning, there is no self, soul, or ego that persists in me from day to day. My body and my psychological states are constantly changing, like the oil and lamps that support the flames. But, like those flames and those lamps, they constitute a causal sequence with a common function. And we have a convention of calling distinct members of such sequences by the same name. So, in one obvious sense, I am not identical to the person called by my name yesterday. We are alike, causally related, but numerically distinct. In another sense, though, we are the same person. We share a name, many properties, a causal history, and a social role; and that, while not involving a self, is enough.

This pair of analogies illustrate the core of the classical Buddhist understanding of what it is to be a person, instead of a self. We are, on this view, causally and cognitively open continua of psychophysical processes. No one of these processes by itself captures who we are; none persist unchanged over time; none are independent of the others. Together, they constitute our conventional identity, an identity we can now see to be very robust indeed, although not fixed. To put this another way, we do not stand over against the world as isolated subjects; we do not act on the world as transcendent agents. Instead, we are embedded in the world as part of an interdependent reality.

To see ourselves as interdependent persons rather than selves has important ethical consequences. Instead of seeing ourselves as detached from others and from the world around us as isolated subjects or agents, we see ourselves as interdependent beings in constant interaction with those around us. To see oneself as a self is to see oneself at the center of the moral universe, a very unhelpful place to be. To see oneself as a person, is to see oneself as embedded in the network of dependent origination that links us to one another. This view supports the development of the qualities referred to as the brahmavihāras, or divine states: maitrī (friendliness); karuṇā (care); muditā (sympathetic joy); and upekṣā (impartiality). Taken together, the brahmavihāras represent an understanding of our moral position not as the center of our universe, but as embedded in a universe with no center. This is a far more realistic place to be and it invites us to approach others with empathetic understanding.[1]

[1] This article is based on material from Losing Yourself: How to be a Person Without a Self, by Jay L. Garfield, forthcoming from Princeton University Press, 2021.