by Ryan Lee Wong

August 23, 2023

I’d believed this gathering was impossible—not because I’d tried and failed to do it, but because my imagination hadn’t allowed me to conceive of it.

Last weekend I attended Roots and Refuge: An Asian American Buddhist Writing Retreat. It was the first of its kind, organized by Chenxing Han and hosted by the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. Thirty-two of us gathered from around the country—from Hawaii to California to Illinois to Texas to New York.

Someone could write a book on all the histories and conversations and writings shared in that retreat (I hope someone does). Here, I want to share a little of what I learned, how the retreat changed me and how it might open a different future for all of us.

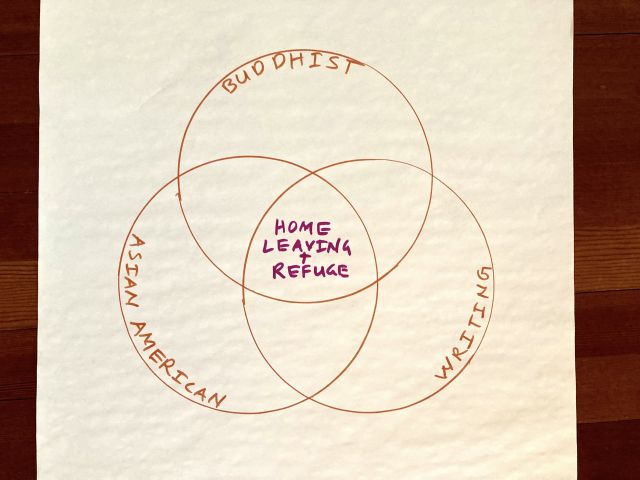

I facilitated an exercise one evening in which we made a timeline of both our Asian American and Buddhist migration stories. I prepared for it by trying to articulate what these three identities and practices—Asian American, Buddhist, Writing—had in common, what bound them. I drew this diagram:

“Home-Leaving and Refuge” came to mind, a twofold process at the center of those overlapping circles.

The Buddha’s followers were called “home-leavers.” They weren’t at first called “Buddhists” or “enlightenment seekers.” They were defined by following the Buddha’s example of leaving their families and homes to take “refuge” in Buddha (the awakened one within all), in dharma (the teachings), and in sangha (the community on the path).

Writing is a practice of home-leaving. We are all raised with family and social stories so embedded that they feel like reality itself. To write is to find new stories, to ask myself what I believe. I think this is the meaning of that saying: “when a writer comes into a family, that is the end of the family.” A writer cannot remain within the family story or within convention. We go to words for refuge, for belonging. We find a home in books, in stories, and then add our own.

And Asian America is shaped by leaving home. Each of us has a story of migration, of crossing an ocean, either in our lifetimes or our ancestors’. Some are literal refugees. We or our ancestors made new homes, sometimes by choice, usually out of necessity. And even though my family on my father’s side has been in America for generations, I feel I am always seeking refuge, a sense of belonging and safety in this troubled land.

All these identities are generally dismissed or erased in our dominant social narratives. Buddhists are seen as a tiny and irrelevant minority within Christian or secular America, and within that, Asian American Buddhists are often condescended to as superstitious ritualists, not ‘real’ Buddhists. I’m often told that writing is a dying form, that video content and A.I. will soon make writing obsolete. And Asian America is seen as politically irrelevant, an uncomfortable reminder of American war and empire, a token minority both perpetually other and proximate to whiteness.

These dismissals and erasures fell away during my first moments at the retreat. It was as if someone unplugged a loudspeaker and we, the retreatants, the refuge seekers, could finally hear each other. And it was a joy to hear. I heard from David, a Korean American priest who offers homies the resources and care they need. I heard from Jude, a dual lineage Jodo Shinshu and Plum Village lineage holder who offered dharma songs and rest practices. I heard from Minna, another young Soto Zen temple director working to bring all their many lineages and identities into this Japanese monastic practice. I heard from Sally, a Qi Gong and Daoist lineage holder and teacher whose movement practices helped reground me between sky and earth. In short, I heard from thirty-one teachers—thirty-one people whose life experiences, stories, and Buddhist embodiments are dharma gates. All of us home-leavers, all of us taking refuge in each other. I felt as if we had always been sangha.

Without that dominant noise, it became clear that we were anything but marginal, that if my imagination had been stifled before it was now freer than ever.

I believe the wisdom of those retreatants and their lineages offer a vital path: learning to leave home and seek refuge is one way we might survive and repair as a society and planet. What better way to face our social division and abuse of the earth than twenty-five centuries of teachings to awaken with and as each other, as the earth itself? How better to understand America’s crises as an empire than to learn from the diasporas that survived and often defied its imperial wars? What better way to articulate our experiences and imagine new worlds than in the creative act of writing?

I want to emphasize that none of this is abstract: these monumental questions arose through bodily relation. They arose as hearing someone’s family heartbreak and being flooded with tears of recognition. They arose as expressing love to someone I’d just met and receiving the same and a hug. They arose as hearing about someone’s Buddhist and Asian lineages being erased then others saying, “I relate,” “I hear you,” “I want to talk about this more.” They arose as chanting in Pali, Chinese, Khmer, English, Korean, Vietnamese, and Japanese; as walking meditation around a stupa carrying Sariputra’s remnants, as silent writing time each morning, as watching a meteor shower in a dark field, as dancing, as creating an ancestral altar, as sharing and holding conflict collectively.

I can’t be more specific, as these stories were expressed in a container of confidentiality. Even more reason to be excited—and feel how essential it is—that this wisdom is being written.

In sangha,

Ryan

Recent Writing by Ryan Lee Wong

- The films Everything Everywhere All At Once and Past Lives both ask what it means to give up one life and embrace a new one through migration. I compare their approaches and reflect upon the grieving process, Buddhism, and racial melancholia for The AMP.

- Nam June Paik, the father of video art, had a fraught relationship to Buddhism that was tied into his complex relationship to Korea, belonging, wealth, and the avant-garde. On the occasion of the release of the documentary Moon is the Oldest TV, I wrote about Buddhism in Paik’s work for PBS American Masters.