Preface and Story

The story of the future Buddha’s birth is one of the most familiar across the Buddhist world. The place of his mother in it is tragic. Mahamaya (or just Maya) died shortly after giving birth, and her child was to be raised by her sister and his adoptive mother, Mahaprajapati Gautami. The miraculous conception of the future Buddha is also one of the most familiar across the Buddhist world: Mahamaya’s pregnancy was the result of a dream that she had about a white elephant.

That dream is mentioned in the story here about Mahamaya’s descent from heaven, where she had been reborn, to see the body of her son in its coffin. Mahamaya finds his body lying under Sala trees, the kind of tree under which she had given birth to him. The Buddha rises from his coffin to speak with his mother one last time.

This story is from a Chinese Buddhist scripture, the Mahamaya Sutra, and the striking scene in it may be unique in Buddhist literature. There is no version of the story in Sanskrit or Tibetan, but it was widely known in China and Japan. In the record of his pilgrimage to India, the 7th-century Buddhist monk Xuanzang recounts this story when he tells about his visit to Kushinagara, the town where the Buddha died.

Story

At that time, Maya, in heaven above, saw the five signs of decay: one, the wilting of the flowers on the head; two, the sweating under the arms; three, the extinguishing of the corona; four, the frequent blinking of the eyes; and five, not enjoying the original seat. She also had five horrible dreams in the night.

One, she dreamed that Mount Sumeru collapsed and that the water of the four seas dried up.

Two, she dreamed that demons holding knives were vying to poke out the eyes of all living beings. Then, a dark storm came, and the demons all ran home to the snowy mountains.

Three, she dreamed that the gods of the desire and form realms suddenly lost their jeweled crowns. They had cut off their own gems and and were not at peace in their original seats. Their bodies were without radiance, like lumps of ink.

Four, she dreamed that the king of wish-granting jewels was above a tall banner and was raining down jewels to all around. Four fire-breathing evil dragons blew the banner down and inhaled the wish-granting jewels. A fierce wind of sickness and evil blew and submerged them into the abyss.

Five, Mahamaya dreamed that five lions came down from the sky and bit her breast, entering on her left side. Her body and mind ached as if she had been stabbed with a sword.

After Mahamaya had seen these dreams, she was suddenly startled awake, and she spoke these words:

“What I faced happened in my sleep. Suddenly, I saw these inauspicious events that caused my body and mind extreme anguish. Long ago I was in the pure royal palace, and I fell asleep during the day and had a strange dream. I saw a god with a golden body riding a white elephant king. Wondrous music came from the gods. The essence of this day-vision entered my right side. My body and mind were at ease, joyful, and without pain or worry. I then became pregnant with Prince Siddhartha, who illuminated the family line as the light of the world. Now, these five dreams were extremely frightening. They must be bad omens that my son Shakyamuni, the Thus Come One, is entering complete nirvana.”

She then turned toward the other gods and spoke at great length about the events she had seen in her dreams.

At that time, Worthy One Aniruddha, who had seen the encoffined corpse, the body of the Thus Come One, ascended to Trayastrimsa Heaven. He went to where Mahamaya was and spoke these verses:

The great teacher, the most excellent god among gods,

the virtuous guide in all the worlds,

has now been swallowed up by that sea of impermanence,

the great fish sea monster.

He is in Kusinagara in Magadha,

Between the twin trees in the sala grove.

Before long, he will leave the city’s eastern gate.

There are various offerings and a funeral pyre.

The assembly brims with gods, humans, and eight kinds of beings.

The cries shake the billion worlds.

After Aniruddha had spoken these verses, he went back down to the place of the Thus Come One’s coffin.

When Mahamaya heard these verses from Aniruddha, she fainted and fell to the ground. The goddesses sprinkled cold water on her face, and after a while, she was revived. She pulled out her hair and cut off all her adornments. Moved to tears, she said these words:

“Last night, I had five bad dreams. They must mean that the Buddha is entering nirvana. Now, as a result, I have seen Aniruddha, who came to say that the cessation is between the twin trees. Before long, I should go to the funeral pyre. Oh, what suffering! The eye of the world has passed into extinction. Oh, what sickness! The fortune of humans and gods is exhausted.

In former days, I was in the pure palace. Seven days after giving birth, I reached the end of my life. In the end, I did not raise him or nurture our affection as mother and son. I entrusted this to Mahaprajapati, made her his aunt-mother, and her milk nourished him. When he grew up and reached the age of nineteen, and he crossed the city walls in the middle of the night and left. The entire palace, inside and out, was grieved. Since achieving the Way, he has opened the wisdom eye of the world and protected all like a compassionate father. How can it be that he must enter nirvana so soon? The burden of impermanence is extremely cruel, and it could harm my child of true awakening.”

Then, amid the assembly, she spoke these verses:

For immeasurable eons

we have always been together as mother and son.

Since you achieved true awakening,

these conditions were forever severed.

Furthermore, in this moment,

you are entering complete nirvana.

It is like a tall, great tree:

a flock of birds rely on it and roost there,

each departing at dawn

and returning at dusk to gather.

Together with you, as mother and son,

we have been at the tree of birth and death.

Since achieving the result of the Way,

you have long severed these original roots.

Furthermore, you are reaching complete extinction.

There will be no more occasions of coming together.

Having spoken these verses, Mahamaya wept and was overcome by anguish.

Surrounded by her retinue of numberless goddesses, who created wondrous music, burned incense, scattered flowers, and chanted praises, she came down from the sky to the site of the twin trees. After arriving among the Sala trees, she saw the Buddha’s coffin from afar, and she fainted and was overcome by anguish. The goddesses sprinkled water on her face, and only then was she revived.

Before arriving at the site of the coffin, she bowed her head and paid her respects. With tears falling in sorrow, she said these words:

“In the past, for innumerable eons, we have long been mother and son and have not been separated. From now on, there will be no more occasions of seeing each other. Oh, the suffering! The merit of all beings is exhausted. Now they will be in delusion. Who will be their guide?”

Then, she scattered divine mandara flowers, mahamandarava flowers, manjusaka flowers, and mahamanjusaka flowers on the coffin and spoke these verses:

Now, between these twin trees

are many gods, nagas and eight kinds of beings.

There is only the sound of weeping,

no one knowing what to say.

Like parrots that squawk in confusion,

they cannot get the words out.

Crowded together on the ground

like birds with broken wings,

they cannot get up and fly toward

the nirvana grove of the Thus Come One.

For vast eons, they have gathered affection

like cataka birds.

Now, the wind of impermanence

sends them to various places.

Living beings in suffering

yearn for the sweet dew of Dharma

like jialanti birds

who long for heavenly rain.

Why must it be now

that he enter nirvana?

His body is hidden in a heavy coffin.

I do not know what comes next for me.

After Mahamaya spoke these verses, she turned and saw the Thus Come One’s patchwork robe and alms bowl together with his staff. Holding them with her right hand, she clapped her head with the left. Her whole body fell to the ground like a crumbling mountain. Her cries of grief subsided, and she said these words:

“In days gone by, my son held these, spreading merit in the world for the benefit of gods and people. Now, these things are empty, without an owner. Oh, the suffering! The pain is unspeakable.”

The eight types of beings and the fourfold assembly saw Mahamaya’s sorrow. It doubled their feelings of sadness, and their tears fell like rain, which Indra transformed into a flowing river.

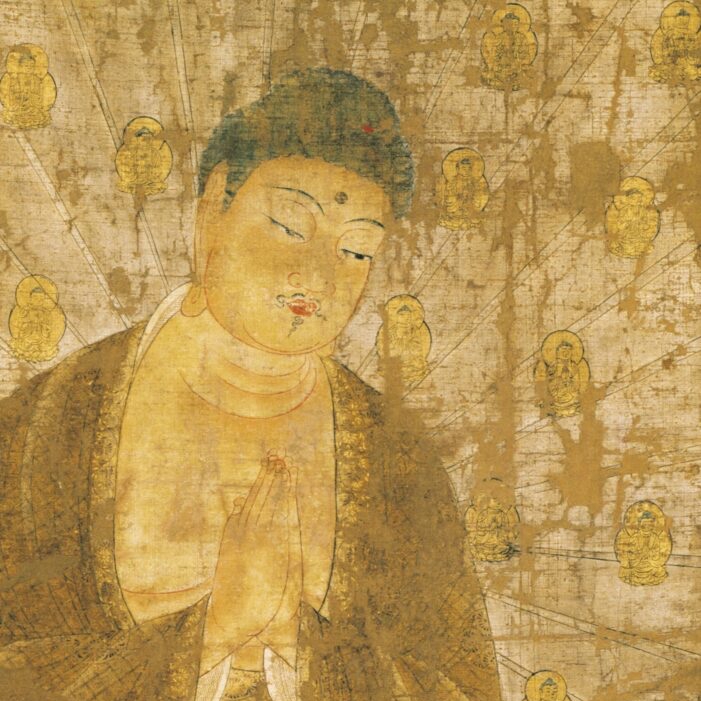

In that moment, the World Honored One used his great supernatural powers to make all the coffin’s coverings open of themselves. He emerged from the coffin with hands in prayer. Like a lion king first coming out of its cave, he was energized and strong. A thousand beams of light shone from the pores of his body. In each and every beam of light were a thousand transformation buddhas, all pressing their palms together in Mahamaya’s direction. In a pure, gentle voice, they greeted his mother, saying,

“You have descended from afar here to Jambudvipa. I wish that you who practice the Dharma would not weep.

Then, on behalf of his mother, they spoke these verses:

Among all the fields of merit,

the Buddha’s field of merit is best.

Among all women,

the treasure among women-jewels is best.

Now, the mother who gave birth to me

is most excellent, incomparable.

She can give birth in the three worlds

to the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha treasures.

For this reason, I have arisen from my coffin

with hands together in joyous praise.

Gratitude from kindness received

has taught me filial affection.

Though buddhas pass into extinction,

the Dharma and Sangha treasures always abide.

I wish that my mother would be without sorrow

and would clearly perceive the unexcelled practice.

After the World Honored One had spoken these verses, Mahamaya was a little comforted. Her face became delighted, like a lotus flower in bloom.

In that moment, Ananda had seen the Buddha rise up, and he had also heard his words in verse. With tears falling and choked words, he restrained himself, pressed his palms together, and spoke to the Buddha:

“In the subsequent age, living beings will surely ask me about the time when the World Honored One was approaching complete nirvana. What do I say? How shall I respond to them?”

The Buddha proclaimed to Ananda, “You should answer in these words: ‘After the World Honored One had entered complete nirvana, Mahamaya came down from heaven to the site of the golden coffin. At that time, the Thus Come One, for the benefit of unfilial living beings of future generations, emerged from his golden coffin like a lion king, strong and energized. From the pores of his body shone a thousand beams of light. In each and every beam of light were a thousand transformation buddhas, all pressing their palms together in Mahamaya’s direction. Altogether, they spoke the verses mentioned above.’”

Ananda also said, “What should this sutra be called? How should we hold it in the mind?”

The Buddha proclaimed to Ananda, “Previously, I ascended to Trayastrimsa Heaven and preached the Dharma for my mother, and Queen Mahamaya also had something to preach herself. Now, furthermore, we are seeing each other here as mother and son. For the benefit of living being of future generations, you can expound this sutra in turn. It is called the Mahamaya Sutra, also known as the Dharma Sutra on the Buddha Ascending to Trayastrimsa Heaven on Behalf of His Mother or the Sutra of Mother and Son Seeing Each Other as the Buddha Approaches Nirvana. Hold it in the mind this way.”

Having spoken these words, the World Honored One bid farewell to his mother, and spoke these verses:

What I was born with has been exhausted.

The pure practices have long been established.

What was created has all been done.

I will take no further existence.

I wish that my mother is comforted

and that she need not suffer and grieve.

All phenomena are impermanent

and abide in this Dharma of arising and ceasing.

Since arising and ceasing have ceased,

serene cessation is the highest joy.

Translated from Chinese for this website by Georgia Kashnig.